Farming was brought to Britain by migrants from continental Europe, and not adopted by pre-existing hunter-gatherers, indicates a new ancient DNA study led by UCL and the Natural History Museum, in collaboration with Harvard University.

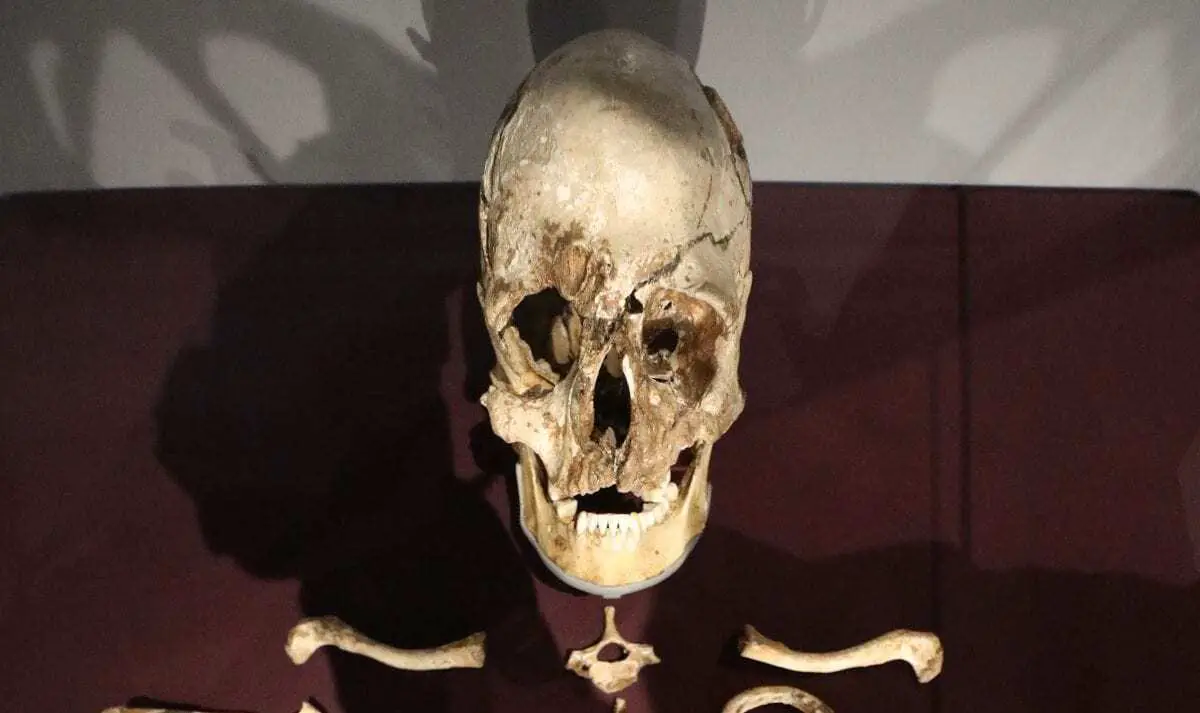

The study, published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, examines the DNA from 47 Neolithic (‘New Stone Age’) farmer skeletons dating from 6000 to 4500 years ago, and six Mesolithic (‘Middle Stone Age’) hunter-gatherer skeletons from the preceding period (11,600-6000 years ago), including Cheddar Man; the oldest near-complete human skeleton found in Britain.

Professor Mark Thomas (UCL Genetics, Evolution & Environment), an author of the study, said, “The transition to farming marks one of the most important technological innovations in human evolution. It first appeared in Britain around 6000 years ago; prior to that people survived by hunting, fishing and gathering. For over 100 years archaeologists have debated if it was brought to Britain by immigrant continental farmers, or if was adopted by local hunter-gatherers.

“Our study strongly supports the view that immigrant farmers introduced agriculture into Britain and largely replaced the indigenous hunter-gatherers populations.”

In continental Europe it is now known that farming was spread by migrating farmer populations who ultimately originated in regions around the Aegean Sea, albeit with some mixing with indigenous hunter-gatherers. Starting around 8000 years ago, they expanded throughout continental Europe along two main corridors: the Mediterranean Sea and the Rhine-Danube axis of Central Europe.

“But Britain is a strange case,” said Dr Tom Booth, archaeologist at the Natural History Museum (NHM) and co-author of the study. “Firstly, farming was practiced for up to 1000 years on the other side of the English Channel before it came to Britain, providing plenty of time for British hunter-gatherers to have adopted agriculture through interactions with their continental neighbours; a view that many archaeologists hold today. And secondly, prior to our study, nobody had read the DNA of those British hunter-gatherers, to see if they had persisted and adopted farming practices themselves.”

Dr Selina Brace, ancient DNA researcher at the NHM and lead author of the study said, “After extracting DNA from Cheddar Man’s inner ear bone, we were delighted at the preservation of his DNA. It’s likely that the cool dry burial conditions in Gough’s Cave were a key factor in keeping his DNA preserved.”

“We found that British Mesolithic hunter-gatherers were closely related to other hunter-gatherers living previously in Western Europe, and shared some aspects of their appearance,” said co-author, Dr Yoan Diekmann (UCL Genetics, Evolution & Environment). “Like their Mesolithic continental relatives, they had typically dark skin but light eye pigmentation”.

Professor Thomas added: “After 6000 years ago we only see farmers in Britain, and their ancestry is different. Not only do they have predominantly the same Aegean ancestry as other continental farmers, but our data suggest that ancestry came to Britain via the Mediterranean corridor”.

Professor Ian Barnes, ancient DNA expert at the NHM and co-author of the study, said: “Because continental farmer populations had mixed to some extent with local hunter-gatherers as they expanded along both the Mediterranean and Rhine-Danube corridors, as well as later, we expected to see some mixing in Britain as well.”

“To our surprise, and with the exception of a few individuals in Scotland, we see little genetic evidence of ancestry from Cheddar Man and British Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in early British farmers, or indeed later. It is difficult to say why this is, but it may be that those last British hunter-gatherers were relatively few in number. Even if these two populations had mixed completely, the ability of adept continental farmers and their descendants to maintain larger population sizes would produce a significant diminishing of hunter-gatherer ancestry over time”.

Co-author Professor David Reich, a Harvard geneticist added: “By studying ancient DNA, we see that 90% of Britain’s population was replaced about 4,500 years ago by large-scale population movement from the continent, and this new study shows a more dramatic 99% replacement a millennium-and-a-half earlier. This means that Briton’s derive only about a thousandth of their ancestry from the hunter-gatherers who inhabited the island ~6,000 years ago, highlighting how people living in any one place today are rarely the primary descendants of the people who lived in the same place in the deep past.”

While the new study answers the old question of whether farming was brought to Britain by continental farmers, it does not answer the question of why it took so long for farming populations to move into Britain after arriving in northwest continental Europe.

The researchers say it may be to do with climate, technology, or perhaps social factors. The megalith-building cultures to which the British Neolithic belongs have a peculiarly maritime focus and emerge out of western France just before the beginning of the Neolithic in Britain.

Dr Brace added: “We see evidence for at least two populations of farmers entering Britain from different parts of continental Europe around the same time. After a thousand years of gazing across the Channel, it is curious to wonder what changed in the circumstances of these farmers which meant that Britain was suddenly seen to be worth the hassle.”

Header Image – Cheddar Man – Credit : geni