A newly identified Christian world chronicle dating to the early 8th century is shedding fresh light on the political and religious upheavals that marked the transition from late antiquity to the rise of Islam.

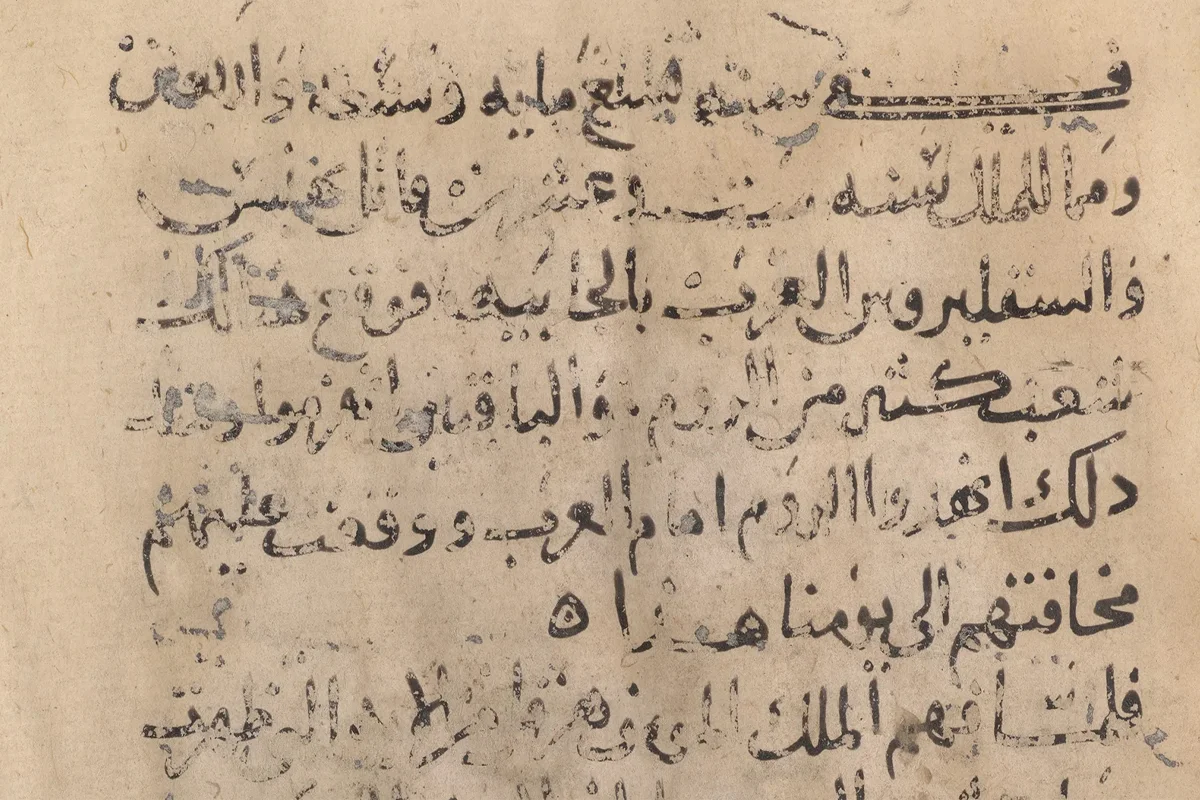

The manuscript, originally written in Syriac and subsequently translated into Arabic, was discovered and examined by researchers from the Austrian Academy of Sciences at St. Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt.

According to experts, the chronicle dates from around AD 712–713 and is among the earliest surviving Christian accounts of the Arab-Islamic expansion.

It chronicles prominent events of the seventh century, including the rise of Islam and the Arab-Byzantine wars, providing rare contemporary perspectives of a watershed period in Middle Eastern history.

Adrian Pirtea of the Institute for Medieval Research discovered the structure while looking at digitised manuscripts found in the Sinai collection. His first findings were recently reported in the journal Medieval Worlds.

The work survives only as an incomplete 13th-century manuscript with pages partially glued together. High-resolution digitisation by the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library and open access through the Sinai Manuscripts Digital Library allowed scholars to study the text for the first time in close detail.

“Since my identification and initial analysis of the text, it has become increasingly clear that this is a previously unknown Christian universal chronicle,” explains Pirtea.

Now referred to as the Maronite Chronicle of 713, the anonymous author narrates human history from Adam to the theological and political debates of his own day.

The chronicle’s pages are penned by a Syriac Christian community that had once identified itself with Constantinople (but would increasingly become estranged over doctrinal issues), yet from which it receives an uncommon glimpse into the east’s reformation during the Islamic period.

Its most valuable sections concern the seventh century, covering the Byzantine–Sasanian War (602–628), the rise of Islam, the early Arab conquests, and subsequent Arab-Byzantine clashes.

The account concludes in 692–693 and demonstrates the author’s awareness of events not only in Syria and the Near East but also in the Balkans, Sicily, and Rome.

A major contribution to scholarship

Pirtea suggests the chronicle may be closely related to a now-lost eighth-century source used by later historians, providing a crucial link for reconstructing early medieval Syriac historiography.

The discovery restores a long-missing Christian perspective on the Near East during Islam’s first century. Pirtea is currently preparing a critical edition and full translation to make the chronicle accessible to scholars worldwide.

Sources : OAW