Native American cultures in the region of the Great Lakes, the Ohio River Valley, and the Mississippi River valley, constructed large characteristic mound earthworks over a period of more than 5,000 years in the United States.

19th century academics theorised that the Native Americans were too primitive to be associated with the mounds, instead, implying that they belonged to a lost culture that disappeared before the arrival of Columbus in 1492.

One of the earliest theories suggested that the mound builders were Norse in origin, who settled in the Americas and migrated south to become the Toltecs in Tula, Mexico. Later theories have connected them with descendants of the Israelites, the Ancient Egyptians, Welsh, Irish, Polynesians, Greeks, Chinese, Phoenicians, and even crossing into the realm of pseudo-science by implying an association with the lost continent of Atlantis.

Proper academic studies have shown that the mounds were built by Native American cultures over a period that spanned from around 3500 BC to the 16th century AD, that includes part of the Archaic Period (8000 to 1000 BC), Woodland Period (1000 BC to AD 1000) and the Mississippian Period (800 AD to 1600 AD).

One of the earliest mound complexes was built at Watson Brake in Louisiana around 3500 BC during the Archaic Period. The site was developed over centuries by a pre-agricultural, pre-ceramic, hunter-gatherer society, who occupied the site on a seasonal basis. The builders constructed an arrangement of eleven earthwork mounds around 7.6 metres in height, connected by ridges to form an oval shaped complex.

Another early site is Poverty Point, a ceremonial mound and ridge complex located on the Bayou Macon also in Louisiana. Poverty Point was constructed over several phases, the earliest being around 1800 BC during the Late Archaic Period, continuing through to 1200 BC. The builders were a society of hunter-fisher-gatherers, identified as the Poverty Point culture, who inhabited stretches of the Lower Mississippi Valley and surrounding Gulf Coast.

The earthworks consist of six concentric C-shaped ridges stretching three-quarters of a mile on the outermost ridge. These encircle a 37.5-acre plaza which contained a series of post circles. The most distinct features from ground level are the mounds constructed using loess, a type of silt loam soil which reaches heights of up to 21.9 metres.

By the Woodland Period, mound-building cultures existed throughout the Eastern United States, stretching as far south as Crystal River in western Florida. One such culture is the Adena culture in Ohio, who mainly built mortuary mounds for burial rituals, in which earth was piled immediately atop a burned mortuary building to form the monument.

Also in Ohio during the Woodland Period is the Hopewell culture, a widely dispersed set of populations connected by a common network of trade routes. People of this culture built complex geometric mounds used for burials, and earthworks which form the shape of animals, birds, or writhing serpents.

The Hopewell created some of the finest craftwork and artwork of the Americas. Most of their works had some religious significance, and their burials were filled with necklaces, ornate carvings made from bone or wood, decorated ceremonial pottery, ear plugs, and pendants.

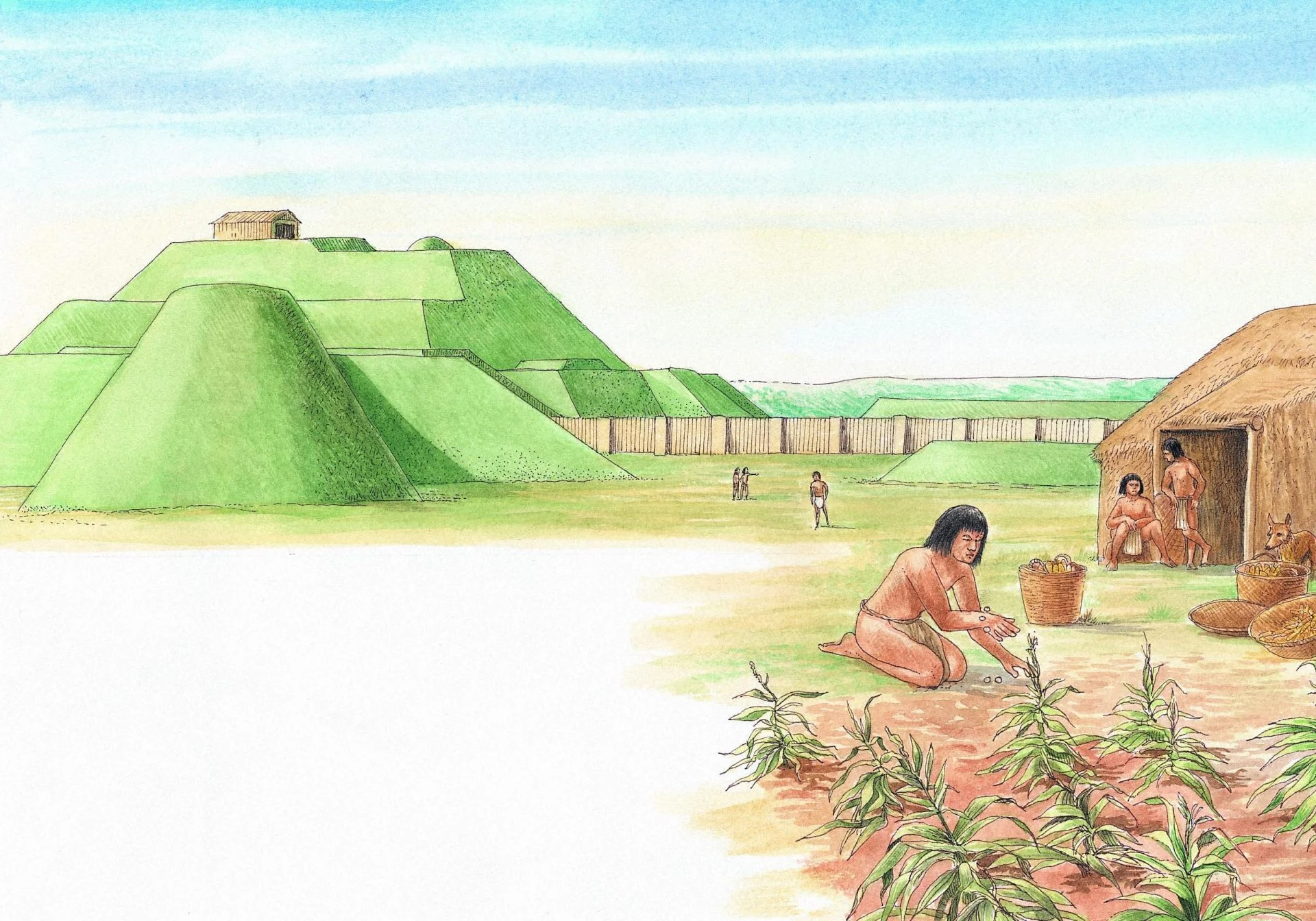

The Mississippian Period saw mound building reaching new heights, with cultures such as the Plaquemine culture and the Mississippian culture, constructing giant platform mounds and settlements that rivalled European cities in size at the time.

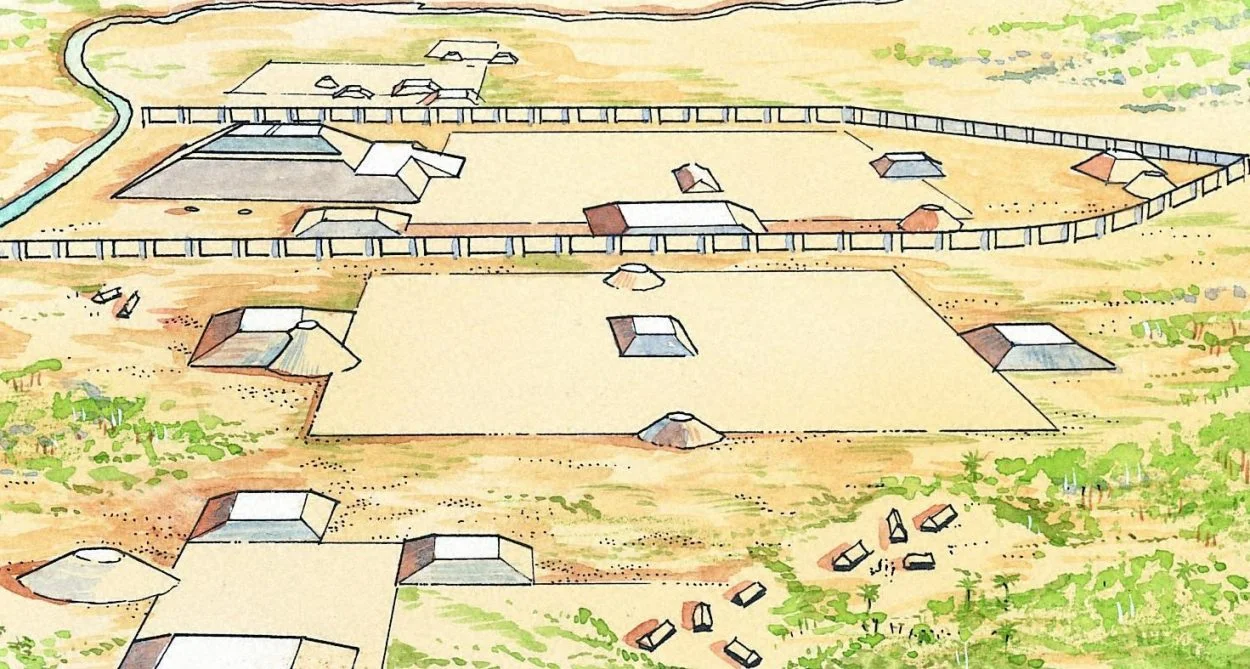

The most famous of these is Cahokia, a centre of the Mississippian Culture that was first constructed around AD 1050 in Western Illinois. Cahokia covered an area between six to nine square miles and contained 120 earthen mounds.

The mounds ranged in size and shape, from raised platforms, conical, and ridge-top designs, with the largest being “Monks Mound” (named after a community of Trappist monks who settled on the mound), a 290-metre-long platform consisting of raised terraces.

After the arrival of Europeans to the Americas, early explorers found the territories of the mound builders largely depopulated and the mounds mostly abandoned. However, there are some accounts, such as the Historia de la Florida by Garcilaso de la Vega, which describes how the Native Americans built mounds and their cultural practices, suggesting a first-hand account from interaction.

One of the last mound builder cultures, the Fort Ancient Culture, likely had contact and traded with Europeans, as evidence of European made goods can be found in the archaeological record. These artefacts include brass and steel items, glassware, and melted down or broken goods reforged into new items.

The Fort Ancient Culture was largely wiped out by successive waves of disease such as smallpox and influenza in the 17th century, suggesting that the population decline in the wider mound building cultures during this period was also a result of disease introduced by the first Europeans to make contact.

Header Image Credit : MattGush – iStock