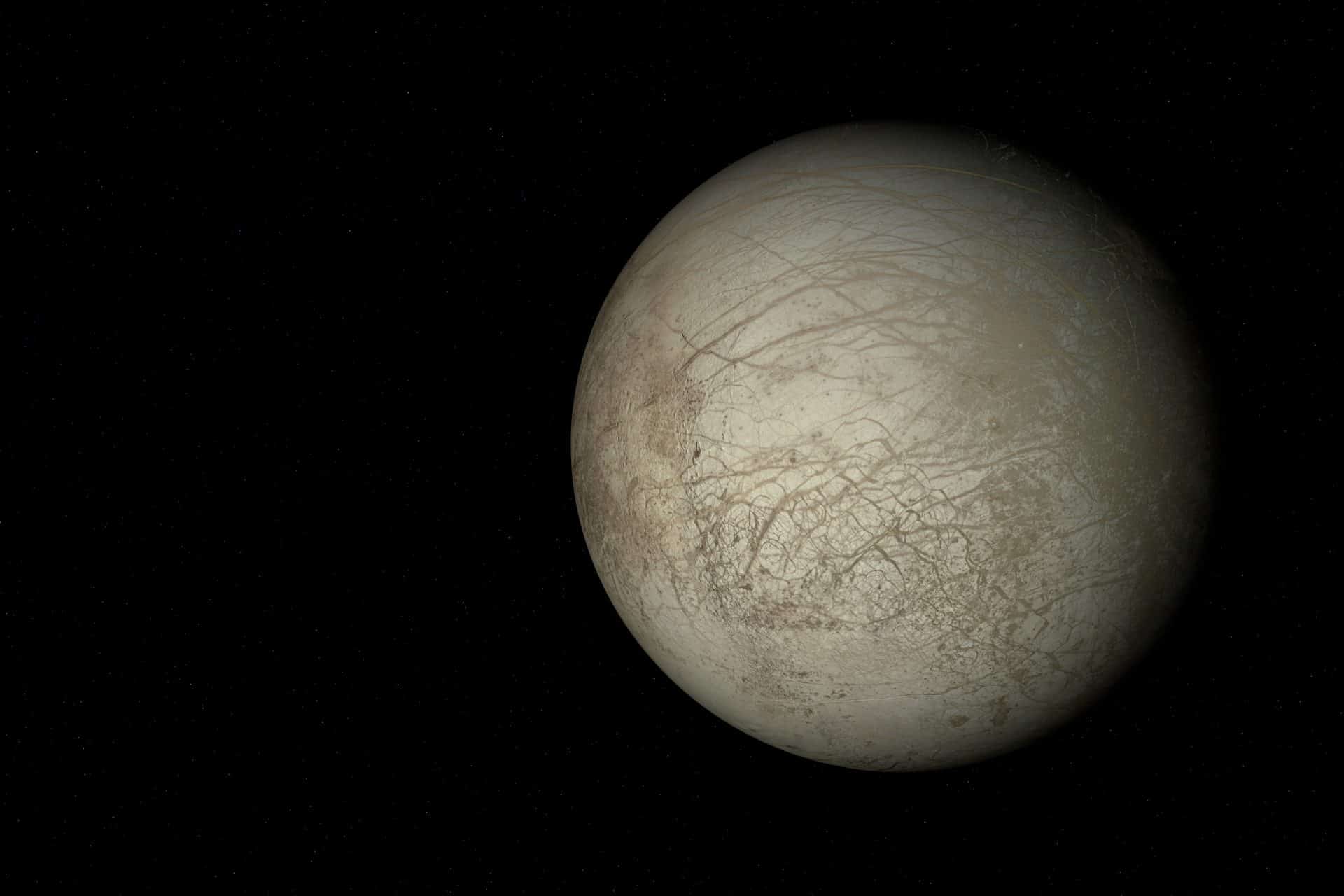

Below Europa’s thick icy crust is a massive, global ocean where the snow floats upwards onto inverted ice peaks and submerged ravines.

The bizarre underwater snow is known to occur below ice shelves on Earth, but a new study shows that the same is likely true for Jupiter’s moon, where it may play a role in building its ice shell.

The underwater snow is much purer than other kinds of ice, which means Europa’s ice shell could be much less salty than previously thought. That’s important for mission scientists preparing NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft, which will use radar to peek beneath the ice shell to see if Europa’s ocean could be hospitable to life. The new information will be critical because salt trapped in the ice can affect what and how deep the radar will see into the ice shell, so being able to predict what the ice is made of will help scientists make sense of the data.

The study, published in the August edition of the journal Astrobiology, was led by The University of Texas at Austin, which is also leading the development of Europa Clipper’s ice penetrating radar instrument. Knowing what kind of ice Europa’s shell is made of will also help decipher the salinity and habitability of its ocean.

“When we’re exploring Europa, we’re interested in the salinity and composition of the ocean, because that’s one of the things that will govern its potential habitability or even the type of life that might live there,” said the study’s lead author Natalie Wolfenbarger, a graduate student researcher at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG) in the UT Jackson School of Geosciences.

Europa is a rocky world about the size of the Earth’s moon that is surrounded by a global ocean and a miles-thick ice shell. Previous studies suggest the temperature, pressure and salinity of Europa’s ocean nearest to the ice is similar to what you would find beneath an ice shelf in Antarctica.

Armed with that knowledge, the new study examined the two different ways that water freezes under ice shelves, congelation ice and frazil ice. Congelation ice grows directly from under the ice shelf. Frazil ice forms as ice flakes in supercooled seawater which float upwards through the water, settling on the bottom of the ice shelf.

Both ways make ice that’s less salty than seawater, which Wolfenbarger found would be even less salty when scaled up to the size and age of Europa’s ice shell. What’s more, according to her calculations, frazil ice – which keeps only a tiny fraction of the salt in seawater – could be very common on Europa. That means its ice shell could be orders of magnitude purer than previous estimates. This affects everything from its strength, to how heat moves through it, and forces that might drive a kind of ice tectonics.

“This paper is opening up a whole new batch of possibilities for thinking about ocean worlds and how they work,” said Steve Vance, a research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) who was not involved in the study. “It sets the stage for how we might prepare for Europa Clipper’s analysis of the ice.”

According to co-author Donald Blankenship, a senior research scientist at UTIG and principal investigator for Europa Clipper’s ice penetrating radar instrument, the research is validation for using the Earth as a model to understand the habitability of Europa.

“We can use Earth to evaluate Europa’s habitability, measure the exchange of impurities between the ice and ocean, and figure out where water is in the ice,” he said.

Wolfenbarger is currently pursuing a doctoral degree in geophysics at the UT Jackson School and is a graduate student affiliate member of the Europa Clipper science team.

The research was funded by the G. Unger Vetlesen Foundation and the Zonta International Amelia Earhart Fellowship.

Header Image Credit : University of Texas at Austin

https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2021.0044