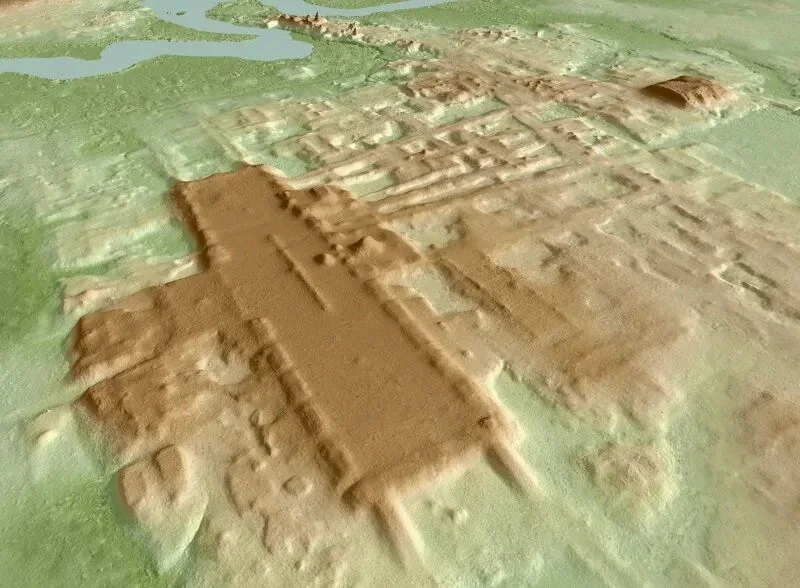

Archaeologists from the University of Arizona have made the monumental discovery of a giant Maya plateau, possibly the largest and oldest Mayan monument discovery to date using LiDar.

Light Detection and Ranging (LiDar) is a method of remote sensing using light in the form of a pulsed laser to measure ranges (variable distances) to the Earth.

The differences in the pulsed laser return times and wavelengths can be used to compile a 3-D digital map of the landscape removing obscuring features such as woodland that could hide archaeological features.

The monument, measuring almost 4600 feet long at a height of 30-50 feet is located at the recently discovered site of Aguada Fénix located in Tabasco, Mexico near the border to Guatemala.

Until now, the Maya site of Ceibal, built-in 950 B.C was considered the oldest confirmed ceremonial centre. The new discovery at Aguada Fénix has been dated to between 1000 – 800 BC using samples of charcoal analysed with a radiocarbon-dating analysis.

Takeshi Inomata, from the School of Anthropology at the University of Arizona said: “Using low-resolution lidar collected by the Mexican government, we noticed this huge platform. Then we did high-resolution lidar and confirmed the presence of a big building. This area is developed – it’s not the jungle; people live there – but this site was not known because it is so flat and huge. It just looks like a natural landscape. But with lidar, it pops up as a very well-planned shape.”

The discovery marks a time of major change in Mesoamerica and has several implications:

First, archaeologists traditionally thought Maya civilization developed gradually. Until now, it was thought that small Maya villages began to appear between 1000 and 350 B.C., what’s known as the Middle Preclassic period, along with the use of pottery and some maize cultivation.

Second, the site looks similar to the older Olmec civilization center of San Lorenzo to the west in the Mexican state of Veracruz, but the lack of stone sculptures related to rulers and elites, such as colossal heads and thrones, suggests less social inequality than San Lorenzo and highlights the importance of communal work in the earliest days of the Maya.

“There has always been debate over whether Olmec civilization led to the development of the Maya civilization or if the Maya developed independently,” Inomata said. “So, our study focuses on a key area between the two.”

The period in which Aguada Fénix was constructed marked a gap in power – after the decline of San Lorenzo and before the rise of another Olmec center, La Venta. During this time, there was an exchange of new ideas, such as construction and architectural styles, among various regions of southern Mesoamerica.

“The extensive plateau and the large causeways suggest the monument was built for use by many people. During later periods, there were powerful rulers and administrative systems in which the people were ordered to do the work. But this site is much earlier, and we don’t see the evidence of the presence of powerful elites. We think that it’s more the result of communal work.” said Inomata.

The fact that monumental buildings existed earlier than thought and when Maya society had less social inequality makes archaeologists rethink the construction process.

“It’s not just hierarchical social organization with the elite that makes monuments like this possible,” Inomata said. “This kind of understanding gives us important implications about human capability, and the potential of human groups. You may not necessarily need a well-organized government to carry out these kinds of huge projects. People can work together to achieve amazing results.”

Inomata and his team will continue to work at Aguada Fénix and do a broader lidar analysis of the area. They want to gather information about surrounding sites to understand how they interacted with the Olmec and the Maya.

Header Image Credit: Takeshi Inomata