Sherlock Holmes is a fictional character that has become a living part of our culture. Since Sir Arthur Conan-Doyle first committed his name to paper in 1887, he has graced thousands of books and hundreds of televised incarnations.

He has remained essentially the same since his conception in 1887. Yet since 1800 the world has undergone a period of the most immense change. In a little over two centuries we have gone from horse power to combustion, from sartorial elegance to the Facebook generation, yet the master of disguise has ironically never even needed one to remain a success. He has been emulated in so many forms, from recent TV’s ‘House’ to Tim Roth’s ‘Lie To Me’.

This success has culminated in the fantastical, masterly incarnation by the BBC, ‘Sherlock’ that has taken the world by storm and unleashed the phenomena of the adventures Sherlock Holmes upon whole new generations of audiences, with t-shirts, apps and even catchphrases available to further titillate the masses. It has fitted neatly into a thoroughly modern paradigm, crystallising the spirit of the books. Even the tagline: ‘A Sleuth for the 21st Century’ is a clever play on the hybridisation of two eras, sleuth being the operative word from a past world.

Due to the success of the new ‘Sherlock’, it is worth looking at the world he was created in. It is possible to view Sherlock Holmes as the bridge between two worlds. Holmes the literary device is a wonderfully realised mirror image of a past that we can no longer see. It can be understood how he is still so relevant to the digital geekery of the 21st century, and how he is essential for the future. It is not the question of who was Sherlock Holmes; it is of why was Sherlock Holmes.

Jack the Ripper

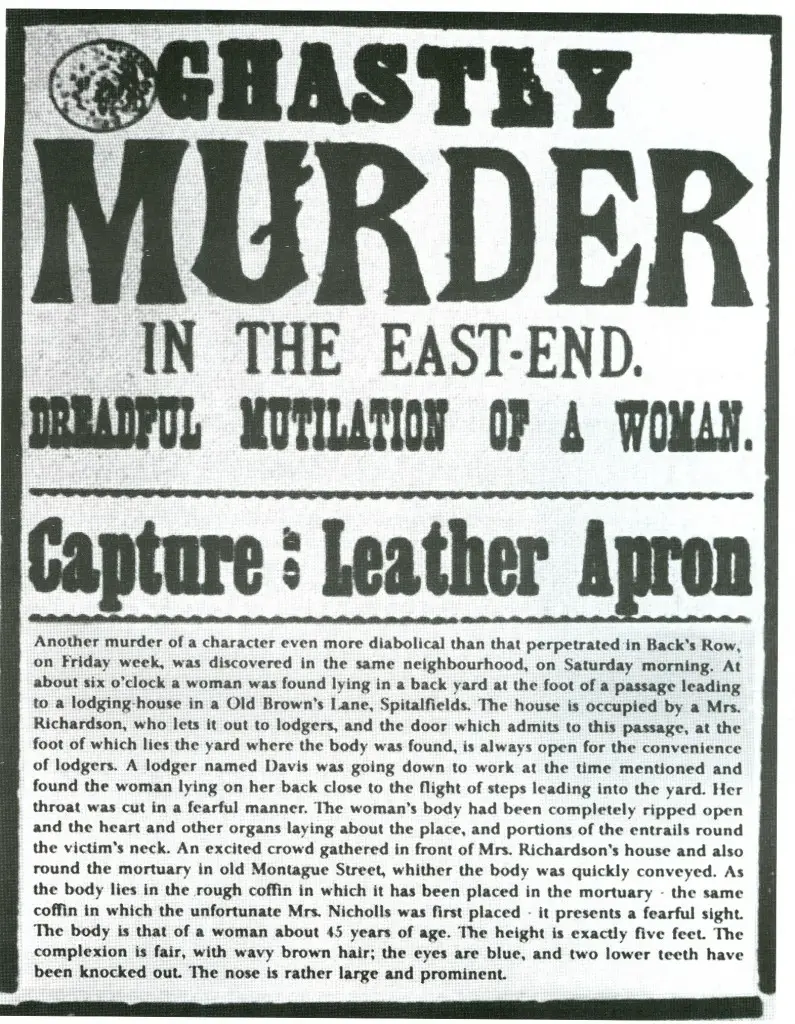

The year is 1888. A grisly and brutal series of events has catapulted a deer stalker wearing vigilante into an international phenomenon, his name is upon thousands of lips. He stalks through the shadows of London’s seedy underbelly, awakening in the world a visceral obsession with crime and detection.

Except this man is not Sherlock Holmes, the most famous of all detectives. This is ‘Jack the Ripper’, the most infamous of all serial killers. Holmes the character was already a year old, and still largely unknown, when Jack went ripping through Whitechapel. Yet it was the Whitechapel murders which changed the nature of Sherlock Holmes’ fortune.

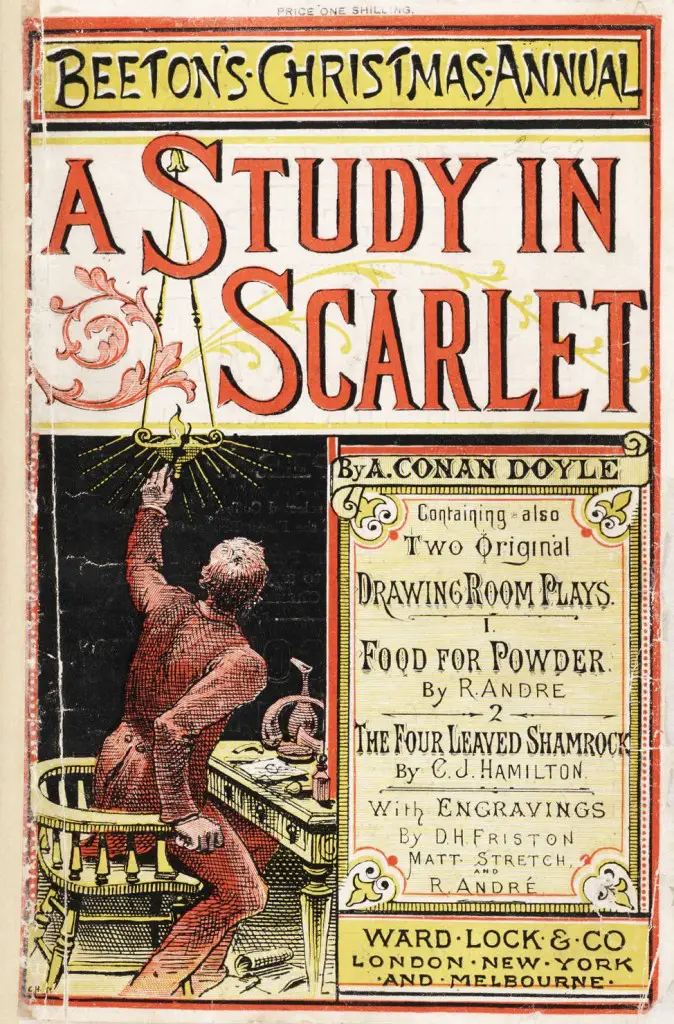

The seeds for the success of Holmes were all sown long before ‘A Study in Scarlet’ was published. It all began with Edgar Allen Poe in 1841 and his creation of Monsieur C. Auguste Dopin, the first true consultant detective. The formula has been relatively unchanged since its conception. A clever and twisted crime takes place and the police always become totally baffled. A brilliant crime breeds a brilliant detective. It is all so reassuringly familiar.

When ‘A Study in Scarlet’ was published in a Christmas annual the year before in 1887 however the reception was lukewarm, people at large didn’t immediately warm to this cold and calculating detective and his Doctor companion. He seemed too alien, perhaps a little too modern.

The brutal slayings of five women in the year of 1888 changed all of that. Sales of Sherlock Holmes stories rocketed. The first story was subsequently re-issued in novel form in the same year, and the rest they say, is history.

A vicious killer on the prowl with seemingly no motive ignited a public scandal that went global, the likes of which had hitherto been unheard of. Jack the Ripper went viral. Fear and disbelief rippled through the streets of the world, of the impoverished and the elite alike. The desperation to find the murderer reached fever pitch. It is illustrated in the issue of ‘The Puck’ magazine from 1888; the confusion is only too evident in its pleading tone.

This cold, seemingly motiveless and utterly mysterious figure that was running rings around the still relatively young Metropolitan Police Force needed to be caught. The public felt the police were bungling and moronic, more prone to scratching their heads than finding the culprit. It didn’t help that hundreds of letters would be sent to Scotland Yard each week, each claiming to be the Ripper. It was a revolution in exposure that the police just weren’t prepared for.

A New Detective for an Evolving World

Enter Sherlock Holmes, the new species of detective that mirrored this public feeling of police inadequacy, to catch the new species of criminal that mirrored the changing nature of society.

Sherlock burst onto a world that was perpetually on the edge of chaos, a world full of great ideas tied down by old ideals. The Ripper killings were a culmination in a new public fascination with the act of murder. The more salacious and debauched the crime, the more the obsession reached fever pitch. The sensational ‘Dr Crippen’ murder case of the early 1900’s that completely seized the world’s attention is a highlight of this trend. This in itself is an ironic product of the civilisation Britain at the time was ardently selling to the world. The British Empire was a term used to illustrate the elegance and optimism of a new world; in reality it just used glittering rhetoric to hide the stench of rot beneath. In Britain it spawned intense immigration, urbanisation and industrialisation, population levels soared, as a result so too did the poverty line. These provided a confusing utopian London, akin to ancient Rome.

Due to this huge population surge in urban centres such as London, for the first time in human history it was possible to be anonymous to your neighbours. The fear of being murdered by somebody you didn’t know was a real possibility.

Newspapers would report the stories with an unhinged fervour, recounting with sadistic glee the grisly details. Scenes of crimes would open as tourist attractions, trinkets pertaining to the murderer and victim would even be sold from little stalls outside. Tours would be arranged of the kill-sites, with Conan-Doyle himself taking a tour of Whitechapel in 1904, even commenting rather reluctantly on how Holmes would catch the elusive killer. Conan-Doyle stated he would study the handwriting of the letters purporting to be the killer.

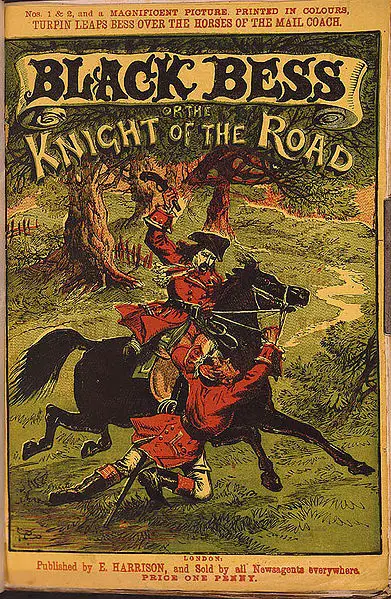

From this bloody atmosphere of seemingly mass sadism, the ‘Penny Dreadful’ became the publication that would define this generation of kill-seekers. The ‘Penny Dreadful’ was a small paper booklet that published lurid tales for only a penny. It is the ‘Penny Dreadful’ that can be accountable for a huge surge in the literacy of the lower classes in the Victorian period, the sensationalism of violence encouraged literacy. The lurid adventures would prove to be an escapism they couldn’t escape from.

Jack the Ripper and Sherlock Holmes share two sides of the same historical coin. The symmetry between the fictional detective and the factual murderer is evident. They both reflect the changing nature of the world. In a bizarre twist of history, one of the only eyewitness accounts attributed to be Jack the Ripper, he is seen wearing a deer stalker. A notion that Jack could have been ‘Sherlocked’ has been advocated by the dreamers of historical narrative, but is purely a sublime coincidence. They share more than that; they are both misfits, outcasts to the society which gave birth to them, both so foreign in their modernism. They are seemingly utterly cold and oblivious to the intricacies of the human condition. Sherlock Holmes then -was a deliciously dangerous hero.

Holmes was the detective the average-Joe approached (as well as the occasional royal visitor) to help in all matters great and small. The great and the good comprised of teachers, lawyers and factory workers. Fictional characters that engineered every adventure reflected the people that really did have to walk the forbidding streets at night, the ones who had read the incredible stories of Sherlock Holmes in the cheap magazines. These were the people that read all about the slayings in Whitechapel, and still clung to the hope he would be caught.

They used the adventures of Sherlock Holmes to escape the horror of their world, and they saw it all through the eyes of a person as bemused and enthralled as them, Dr John Watson. Watson is arguably is the true masterstroke by Conan-Doyle, the realisation of the ordinary. Watson is the heart of Sherlock Holmes, he provides counterbalance and he is the epitome of the era; he is the archetypal Victorian gentleman. If Holmes was a glimpse into the future, it was Watson who provided the tentative link to the past.

Technology and Technique

Interwoven seamlessly with Victorian characterisation is Sherlock’s love for science and technology. This in itself is a reflection of the time he was created. The huge technological boom that occurred in the 19th century was perfectly timed. Britain was reaping the fruits of imperialism, knowledge and ideas from all corners of the globe landed in London in 1851 in the famous ‘Great Exhibition of the Works and Industry of All Nations’ commonly known as the ‘Crystal Palace’. It was the first internet, transmitting the fruits of intelligence to one and all.

The first image we have of Holmes in ‘A Study in Scarlet’- and one that could just as easily fit that of a murderer – he is viciously beating a corpse with a stick to evaluate bruising of the flesh post-mortem, a scientific technique still in its infancy. With the creation of Sherlock, no longer was it pioneered in a remote corner of a laboratory, it was thrust into the public imagination. It spawned a public fascination in forensic science that still resonates today. Open up any television guide, the panoply of forensic detective shows immediately jumps off the page. Contrary to popular belief, he didn’t pioneer forensic science. What he did do – and still does – was make it sexy.

He helped to galvanise a development in the importance of observation, a technique advocated by Conan-Doyle’s own teacher, Dr. Joeseph Bell. It would further go on to inspire hundreds of different disciplines of physical psychology, such as ‘kinesics’, or how to read body language. Never has a fictional character had such an effect on the world of real science.

This love of the new and technological is excellently interwoven in the recent incarnation, with his use of iPhones, blogging and even nicotine patches. The nicotine patches are the well-heeled homage to the darker side of Holmes’s character, his dependence on narcotics – notably, his calculated use of cocaine. This is a shock to us, but to the Victorian world recreational drugs were hardly understood at all, but they still carried the same euphoric effects that culminated in a socially acceptable but incredibly dangerous pastime.

He is a fictional character that can be placed in any reality past or present, and be made utterly real. Even today, 221B Baker Street receives thousands of correspondence from people all the world beseeching Holmes to help them. To millions, he really exists. Such is the draw of Holmes; London has recently suffered a surge in tourism, thanks to a character almost a century and a half old.

On an elemental level, there is something deeply reassuring about Sherlock Holmes. His frosty relationship with his brother, his proneness to dark depression and his incredibly addictive personality resound not just with the people who lived in his time, they are incredibly close to us too. His genius resides in how he overcomes his fallibilities, and in there somewhere is a dark optimism that cannot be quantified. His absolute dedication to justice, not human emotion, further rockets him to heroic status. He was created as the ultimate anti-hero in a world that needed exactly that. He was, and still is, the literary device that carries upon his back the ability to make sense of an ever evolving world.

Written by Paddy Lambert