A recent study led by UCL researchers has discovered that Neanderthal genetic material inherited by humans has an impact on the shape of our noses.

According to a study published in Communications Biology, a specific gene that results in a taller nose (measured from top to bottom) might have undergone natural selection as early humans adapted to colder environments after migrating out of Africa.

Dr. Kaustubh Adhikari, co-corresponding author of the study from UCL Genetics, Evolution & Environment and The Open University, stated that since the sequencing of the Neanderthal genome 15 years ago, it has been discovered that our ancestors interbred with them, resulting in small fragments of their DNA present in our genome.

“Here, we find that some DNA inherited from Neanderthals influences the shape of our faces. This could have been helpful to our ancestors, as it has been passed down for thousands of generations,” said Dr Adhikari.

For the study, data from over 6,000 volunteers with mixed European, Native American, and African ancestry in Latin American countries – including Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Mexico, and Peru, were gathered by the UCL-led CANDELA study.

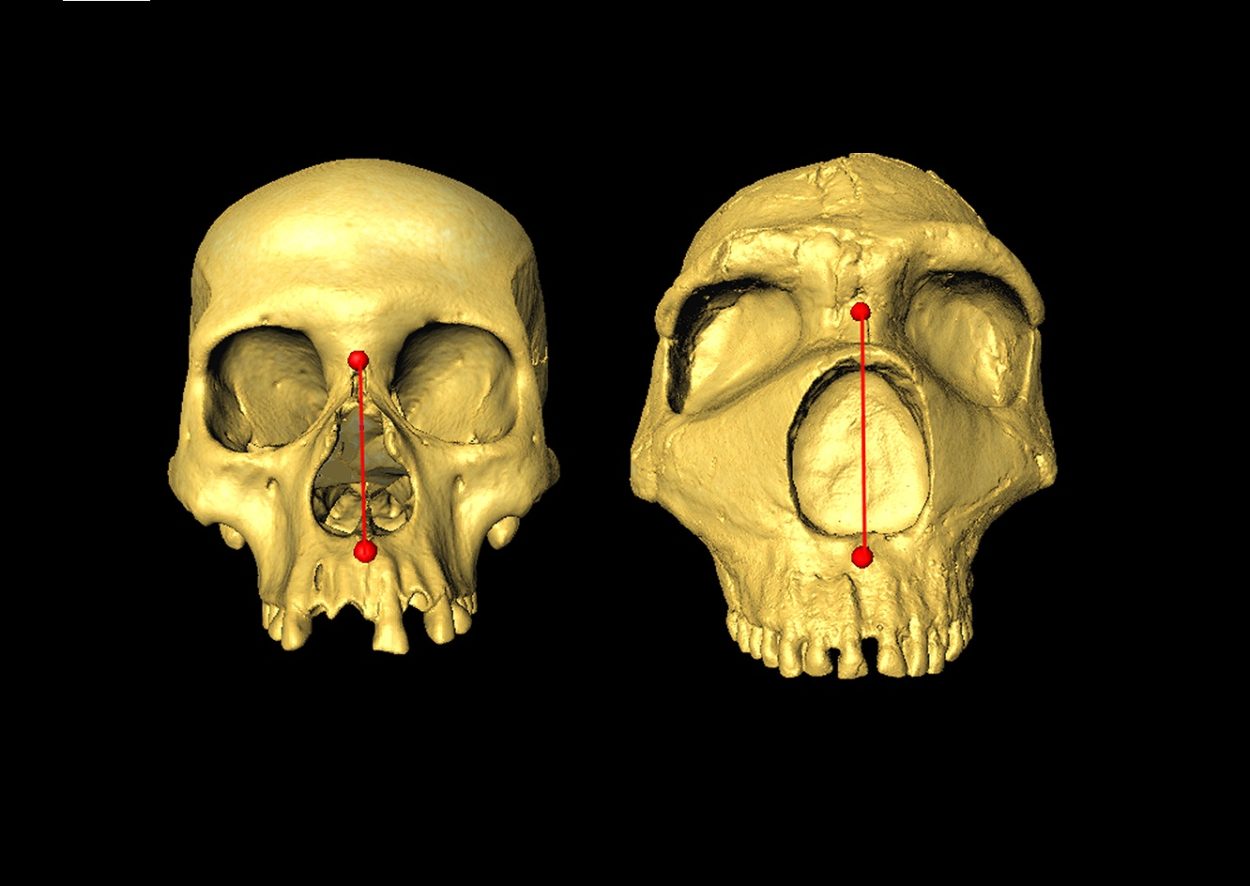

The team utilised photographs of the participants’ faces, focusing on the distances between specific points such as the tip of the nose or the edge of the lips, to investigate the correlation between various facial features and the presence of distinct genetic markers.

The researchers newly identified 33 genome regions associated with face shape, 26 of which they were able to replicate in comparisons with data from other ethnicities using participants in east Asia, Europe, or Africa.

The scientists observed that a specific genome region, known as ATF3, exhibited an interesting pattern. Individuals with Native American ancestry, as well as those with East Asian ancestry from another study, possessed genetic material in this gene inherited from Neanderthals, which led to a higher nasal height. Moreover, the gene region displayed signs of natural selection, indicating that it conferred an advantage to individuals carrying this genetic material.

First author Dr Qing Li (Fudan University) said: “It has long been speculated that the shape of our noses is determined by natural selection; as our noses can help us to regulate the temperature and humidity of the air we breathe in, different shaped noses may be better suited to different climates that our ancestors lived in. The gene we have identified here may have been inherited from Neanderthals to help humans adapt to colder climates as our ancestors moved out of Africa.”

Co-corresponding author Professor Andres Ruiz-Linares (Fudan University, UCL Genetics, Evolution & Environment, and Aix-Marseille University) added: “Most genetic studies of human diversity have investigated the genes of Europeans; our study’s diverse sample of Latin American participants broadens the reach of genetic study findings, helping us to better understand the genetics of all humans.”

Header Image Credit : Dr Kaustubh Adhikari, UCL