The flower wars were semi-ritual battles fought between members of the Aztec Triple Alliance and surrounding city-states, in which participants followed a strict set of conventions at sacred sites known as cuauhtlalli or yaotlalli.

Most of what we know about the flower wars comes from the few codices to survive the Spanish conquest, and from accounts recorded in early Hispanic texts by the conquistadors.

The wars raged intermittently from the mid-1450s to the arrival of the Spaniards in 1519, in which warriors from Tenochtitlan (the Aztec capital), Texcoco, Tlaxcala, Cholula, and Huejotzingo, agreed to engage in the flower wars for several strategic and ritualistic purposes.

Historians believe that the Aztecs used the wars to provide military training for their warriors, and to test the strength of the contending forces so that the Aztecs could defeat or intimidate them to force a change of allegiance, especially in situations where the Aztecs were unable to defeat enemy states using conventional warfare.

The wars were also used to obtain human sacrifices to appease the appetites of the Aztec pantheon of gods, which may have originated from periods of crop failure and severe drought and famine, requiring human sacrifices to bring rains and a good harvest.

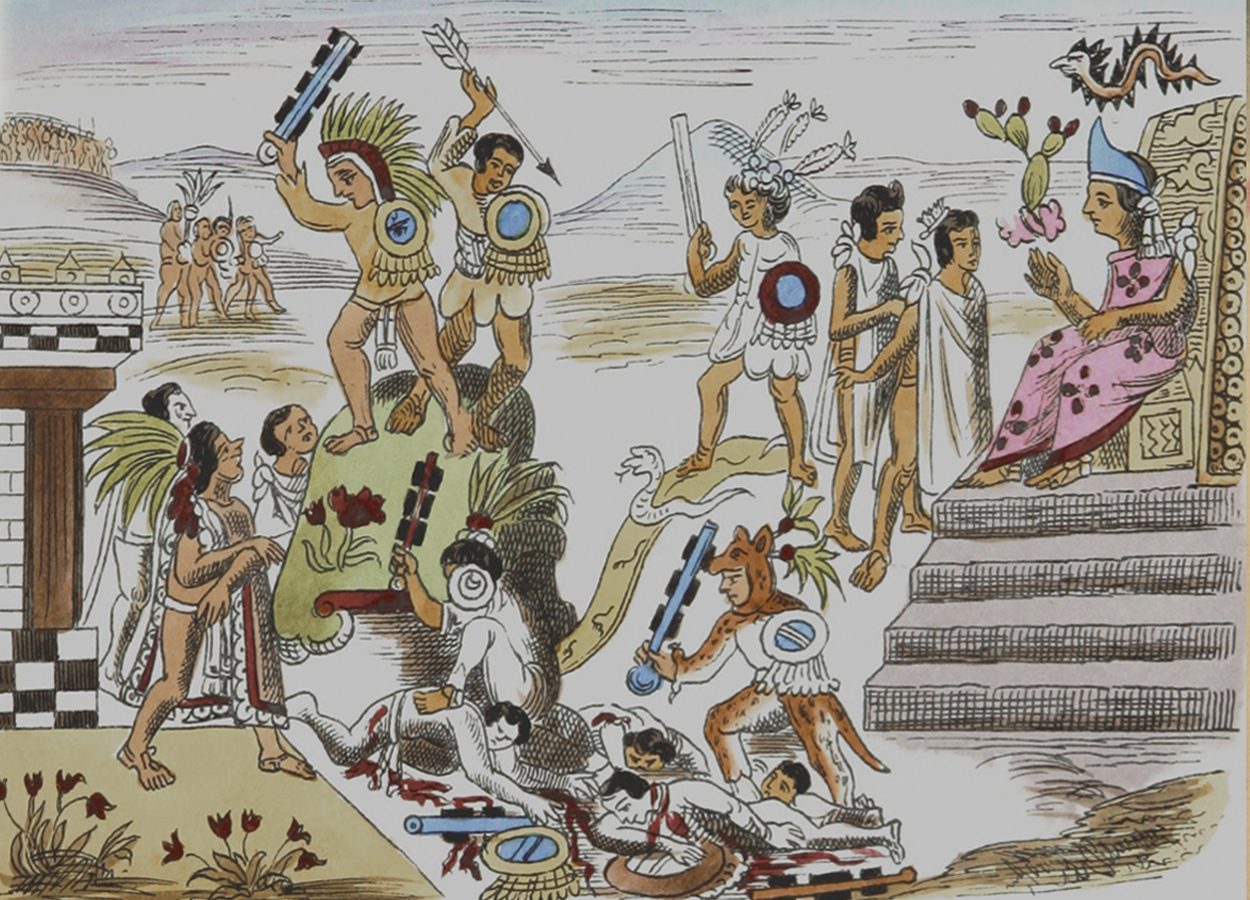

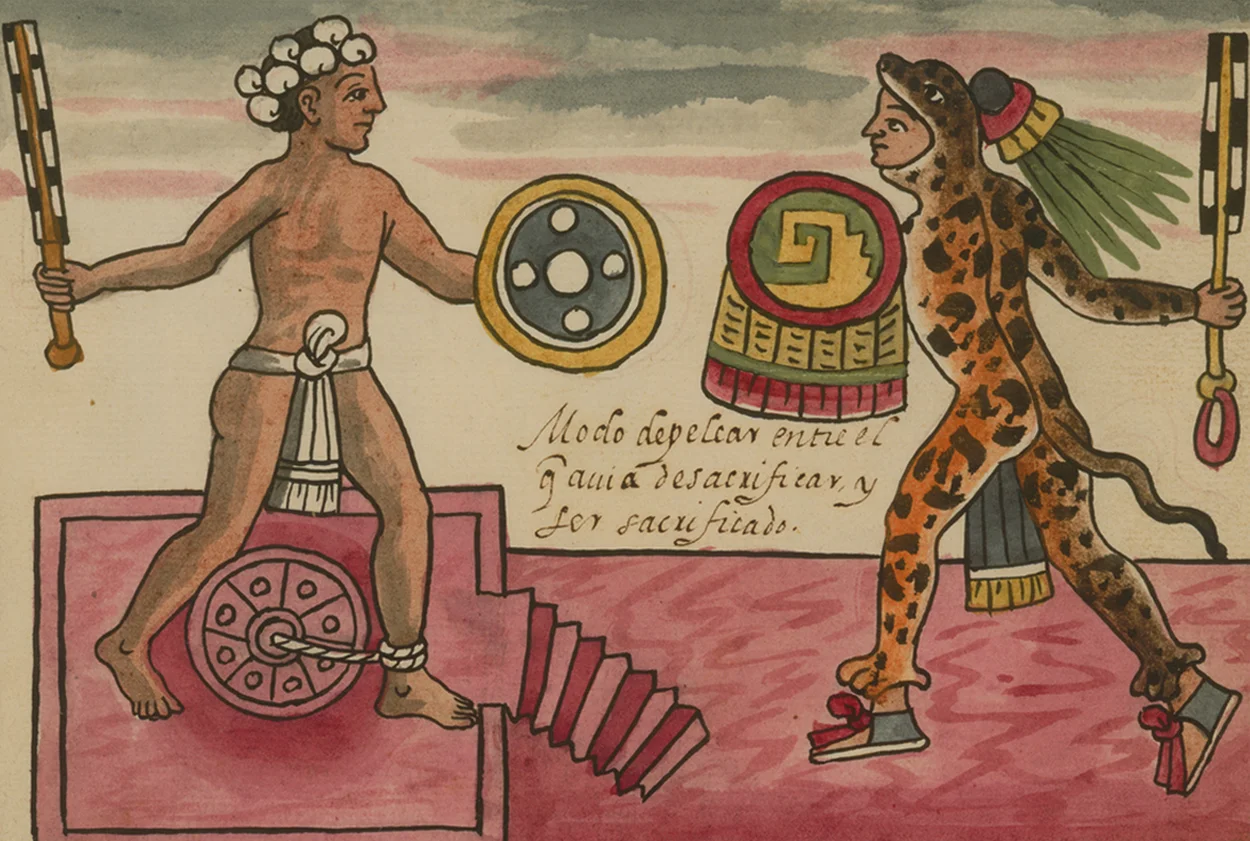

Selected warriors from the nobility and lower classes of each city state would signal the start of the flower wars by burning a large pyre. Rather than use long range weapons, warriors would demonstrate their individual combat skills by using close quartered weapons such as the macuahuitl, a wooden club with several embedded obsidian blades.

The Aztecs considered a death during the flower wars to be more noble than dying in a typical war; this can be seen in the word for a flower war death, xochimiquiztli, which translates to “flowery death, blissful death, fortunate death”.

Furthermore, the Aztecs believed that those who died in a flower war would be transported to the realm of Huitzilopochtli, the supreme god of sun, fire, and war, and the patron god of the Aztec people.

Warriors captured in battle were transported to the Great Temple, or El Templo Mayor, a large, stepped pyramid in the capital city of Tenochtitlan. Sacrificial rites vary, but the most common involved the removing of the heart by temple priests while the victim was still alive.

The heart was considered the ultimate symbol of a person’s life and was presented to the gods in a Cuauhxicali, or Eagle Vessel. It was then burnt, enabling the life force to rise via the smoke to Huitzilopochtli, who would take on new strength and go on giving light and warmth to the Aztec people.

Header Image Credit : Mabarlabin – CC BY-SA 3.0