Archaeologists have conducted a study of hundreds of ancient “bog bodies” found in Europe’s wetlands, revealing that they were part of a tradition that spanned a millennia.

A bog body refers to a human corpse naturally preserved in a peat bog. The exceptional preservation occurs due to the bog’s highly acidic water, low temperatures, and limited oxygen, which effectively conserve elements like skin, hair, nails, and even internal organs.

People were buried in bogs as early as the prehistoric period, with the oldest known bog body being 10,000-year-old Koelbjerg Man from Denmark. Some of the most well-known examples are Lindow Man from the United Kingdom, Tollund Man from Denmark, or Yde Girl from the Netherlands.

Due to the high level of preservation, bog bodies enable scientists to reconstruct aspects of the individual’s life in the distant past, such as their last meal from traces preserved in the stomach, or even the cause of death.

Many bog bodies show a number of similarities, such as violent deaths and a lack of clothing, which has led archaeologists to believe that they were killed and deposited in the bogs as a part of a widespread cultural tradition of human sacrifice mainly during the Iron Age.

“Literally thousands of people have met their end in bogs, only to be found again ages later during peat cutting,” said Doctor Roy van Beek, from Wageningen University, “The well-preserved examples only tell a small part of this far larger story.”

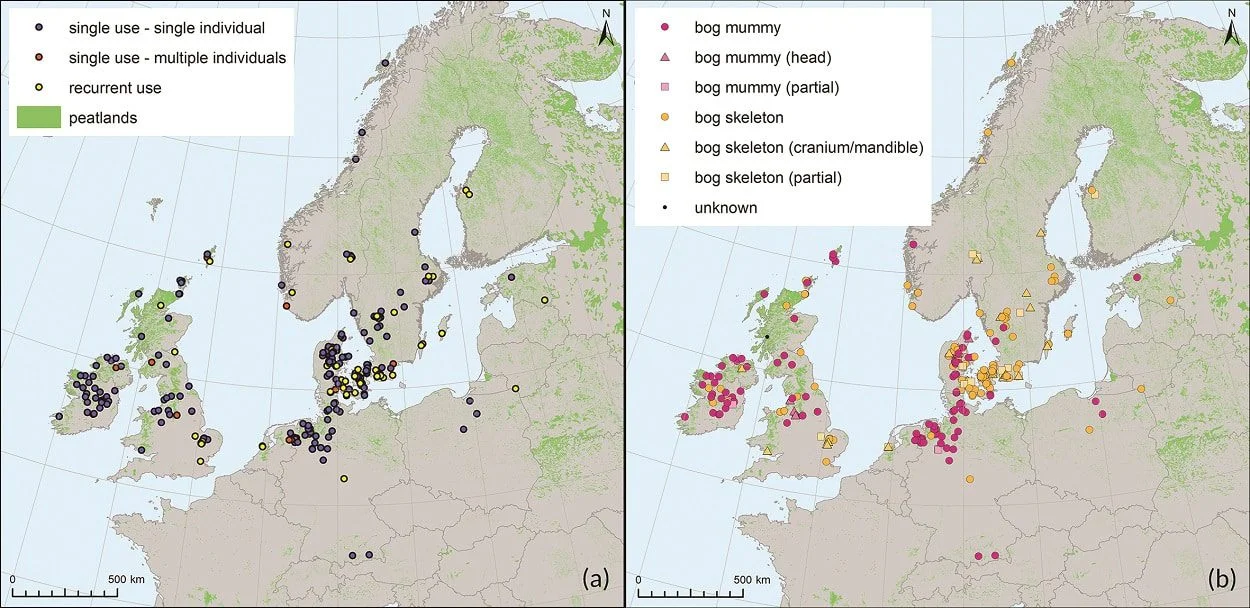

A new study, published in the journal Antiquity, has analysed over 1000 bog body remains from 266 sites across Europe. The researchers have divided the study cases into three main categories: ‘bog mummies’ – where the skin, soft tissue, and hair are preserved, ‘bog skeletons’ – with only the bones surviving, and the third category being the partial remains of either bog mummies or skeletons.

The study has revealed that the bog body practice is part of a millennia-long, deep-rooted tradition. The phenomenon starts in southern Scandinavia during the Neolithic around 5000 BC, and gradually spread over Northern Europe. The most recent discoveries, found in Ireland, the United Kingdom, and Germany, indicate that this tradition persisted through the Middle Ages and into the early modern period.

Where a cause of death could be determined, the majority appear to have met a gruesome end and were likely intentionally left in bogs. The acts of violence are commonly perceived as ritualistic sacrifices, the punishment of criminals, or victims of violent acts. Nevertheless, historical records from recent centuries suggest a notable occurrence of accidental deaths and instances of suicide in bogs.

“This shows that we should not look for a single explanation for all finds,” said Doctor van Beek, “accidental deaths and suicides may also have been more common in earlier periods.”

The research has identified instances of “bog body hotspots” in wetlands where multiple individuals’ remains have been discovered. In some cases, these findings signify singular events, such as the collective interment of casualties from a battle.

Other bogs were used time and again, and the human remains were accompanied by a wide range of other objects that were interpreted as ritual offerings, ranging from animal bones to bronze weapons or ornaments.

These marshy areas are seen as sites of religious significance, likely occupying a central role within the belief systems of local communities. Another notable category comprises what are termed ‘war-booty sites,’ where substantial amounts of weaponry are discovered alongside human remains.

“All in all, the fascinating new picture that emerges is one of an age-old, diverse, and complex phenomenon, that tells multiple stories about major human themes like violence, religion, and tragic losses,” said Doctor van Beek.

https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2022.163

Header Image : Tollund Man – Image Credit : Sven Rosborn – Public Domain