At first glance, it might seem that archaeology and ecology don’t have much in common. One unearths the ancient human past; the other studies the interactions of living organisms.

But taking the long view in understanding humans’ influence on ecosystems and vice versa can provide new insights in both fields, according to a new study by researchers from the Santa Fe Institute, Utah State University, and the University of Washington.

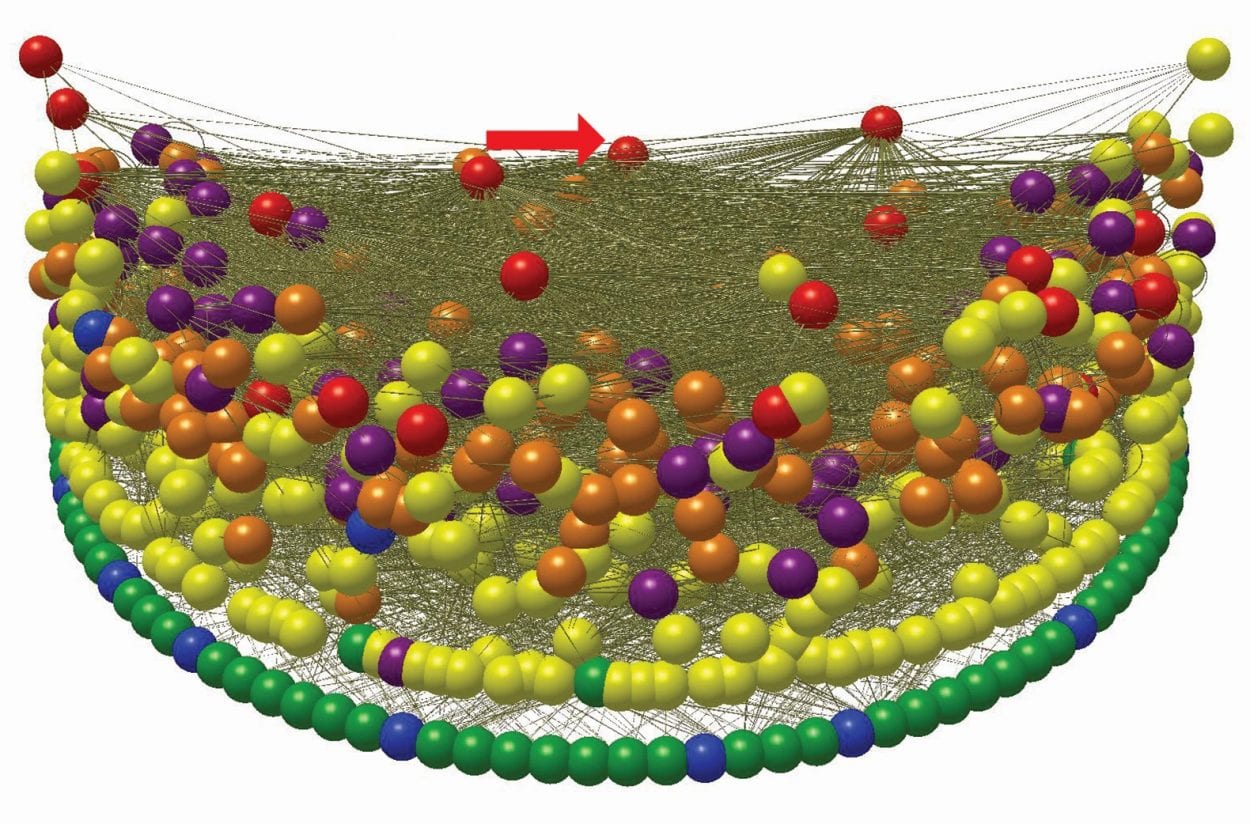

Employing ecological tools such as food web modelling can help archaeologists create a fuller picture of the ways people interacted with their environment in the distant past. At the same time, as archaeologists reconstruct the human-environment relationship in ancient communities, those insights can better inform ecologists’ ideas of how the past has shaped the present, and humanity’s place in today’s ecosystems, says archaeologist Stefani Crabtree of SFI and Utah State University, the lead author of the study published Friday in the journal Antiquity.

“Because we have this record of people going out into the environment and bringing things back home, and then those things being deposited in middens, or trash heaps, we actually have a really good record of how people were interacting with the environment,” she says. “They did all kinds of things to modify their environment. And so we can look back in the archaeological record, and it can help calibrate our understanding of our ecosystems today.”

Ancient communities may seem far removed from us, but they have much to teach us, she adds. “Archaeology can save the future. It really can. Because this gives us an idea of the human place within the environment.

It tells us where we’re sustainable, and where we’re not. In this way archaeology gives us an ability to see past experiments with sustainability,” says Crabtree. “And so that’s what really drew me to doing this research, was using the past as a way to calibrate our understanding of our place in the environment.”

One example of how the past can inform the present lies in recent work on marine food webs in the Aleutian Islands, a volcanic archipelago in the Bering Sea. That research, cited in the study, found that the islands’ first inhabitants, who arrived there ca. 7,000 years ago, lived within their ecological means. “This human population was poised to have negative impacts on the ecosystem, but there is no evidence they did,” says ecologist and complexity scientist Jennifer Dunne of SFI,* who co-authored that study as well as the new paper along with ecologist Spencer Wood at the University of Washington.

That’s in part because the population remained low, but also because “they only used higher-impact hunting technology intermittently, as opposed to lower-impact foraging. Also, when preferred prey became less available to them, they switched to other prey species,” relieving pressure on the preferred food source. “It appears that they were able to become part of the food web without destroying the ecosystem,” Dunne adds. “I think there’s an important lesson there.”

Such lessons could benefit the commercial fisheries in the northern Atlantic, where overfishing has decimated stocks in some areas, adds Wood. “Those fisheries have been fished for thousands of years, so to only look at the past few decades is pretty short-sighted. We’d have a lot better understanding of the effects humans have on them if we look at much deeper time, and you can’t do that without having this archaeological and ecological collaboration,” he says. “If we can, we’ll have a better sense for how to manage them sustainably.”

The researchers hope the paper will inspire archaeologists and ecologists to work together more often and shine new light on what it means to inhabit an ecosystem sustainably.

“A lot of it’s about how to understand when humans are likely to have negative impacts, when they’re neutral and when they may even enhance ecosystem functioning,” Dunne says. “We’re just at the beginning of our understanding.” Find out more

Header Image Credit : Antiquity