Matthew Hopkins was an infamous witch-hunter during the 17th century, who published “The Discovery of Witches” in 1647, and whose witch-hunting methods were applied during the notorious Salem Witch Trials in colonial Massachusetts.

From the 16th century, England was in the grips of hysteria over witchcraft, caused in part by King James VI, who was obsessed with the dark arts and wrote a dissertation entitled “Daemonologie” in 1599.

James had been influenced by his personal involvement in the North Berwick witch trials from 1590, and amassed various texts on magical studies that he published into three books to describe the topics of magic, sorcery, and witchcraft, and tried to justify the persecution and punishment of a person accused of being a witch under the rule of canonical law.

The published works assisted in the creation of the witchcraft reform, that led to the English Puritan and writer – Richard Bernard to write a manual on witch-hunting in 1629 called “A Guide to Grand-Jury Men”. Historians suggest that both the “Daemonologie” and “A Guide to Grand-Jury Men” was an influence that Matthew Hopkins would draw inspiration from and have a significant impact in the direction his life would take many years later.

Matthew Hopkins was born in Great Wenham, located in Suffolk, England, and was the fourth son of James Hopkins, a Puritan vicar of St John’s of Great Wenham. After his father’s death, Hopkins moved to Manningtree in Essex and used his inheritance to present himself as a gentleman to the local aristocracy.

Hopkins’ witch-finding career began in March 1644, when an associate, John Sterne alleged that a group of women in Manningtree were conducting acts of sorcery and were trying to kill him with witchcraft. Hopkins conducted a physical investigation of the women, looking for deformities and a blemish called the “Devil’s Mark” which would lead to 23 women (sources differ in the number) being accused of witchcraft and were tried in 1645. The trial was presided over by the justices of the peace (a judicial officer of a lower or puisne court), resulting in nineteen women being convicted and hanged, and four women dying in prison.

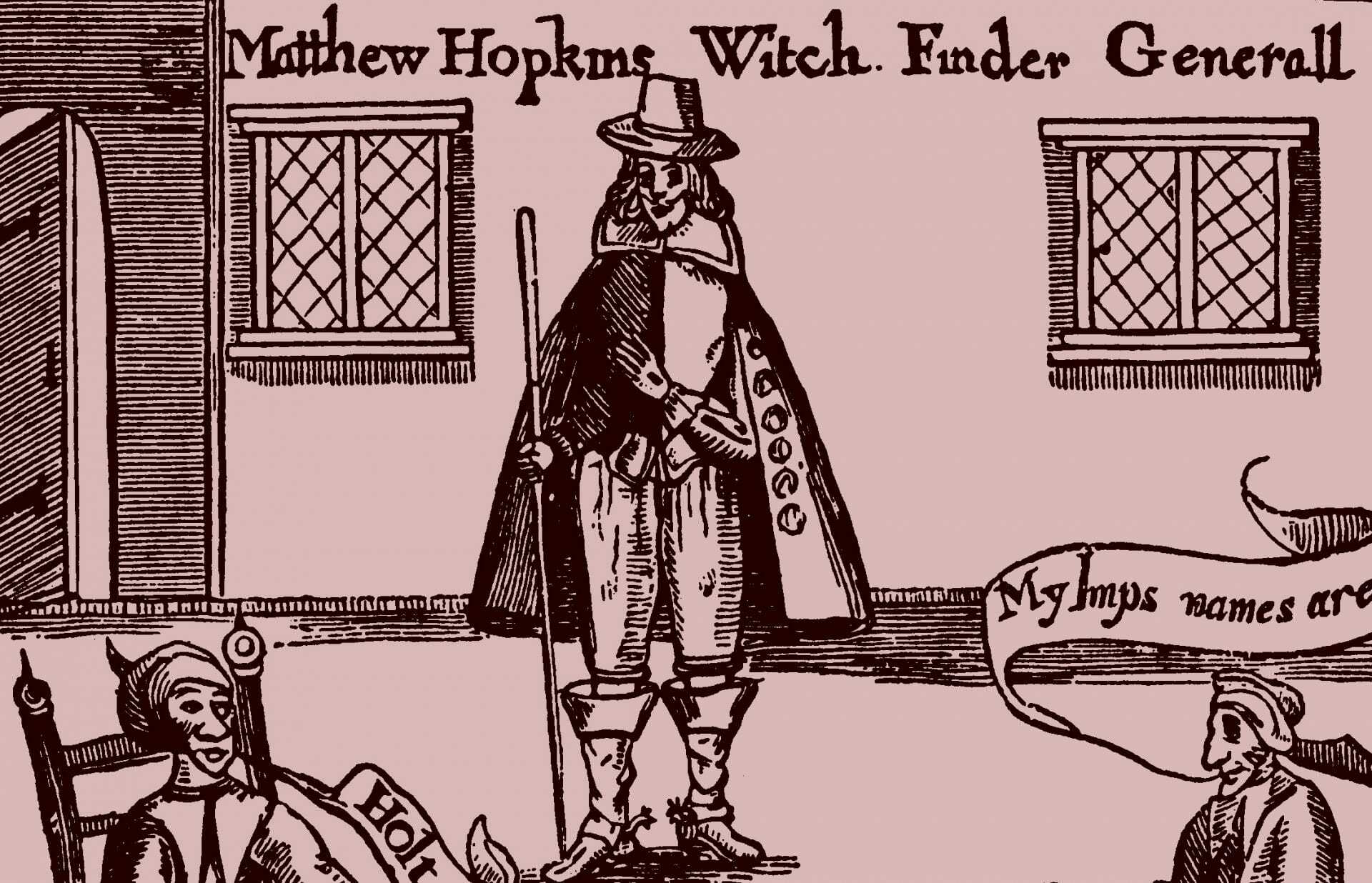

After their success in the trail, Hopkins and Stearne travelled throughout East Anglia and nearby counties with an entourage of female assistants, falsely claiming to hold the office of Witchfinder General and also claimed to be part of an official commission by Parliament to uncover witches residing in the populous by using a practice called “pricking”. Pricking was the process of pricking a suspected witch with a needle, pin or bodkin. The practice derived from the belief that all witches and sorcerers bore a witch’s mark that would not feel pain or bleed when pricked.

Although torture was considered unlawful under English law, Hopkins would also use techniques such as sleep deprivation to confuse a victim into confessing, cutting the arm of the accused with a blunt knife (if the victim didn’t bleed then they’d be declared a witch) and tying victims to a chair who would be submerged in water (if a victim floated, then they’d be considered a witch).

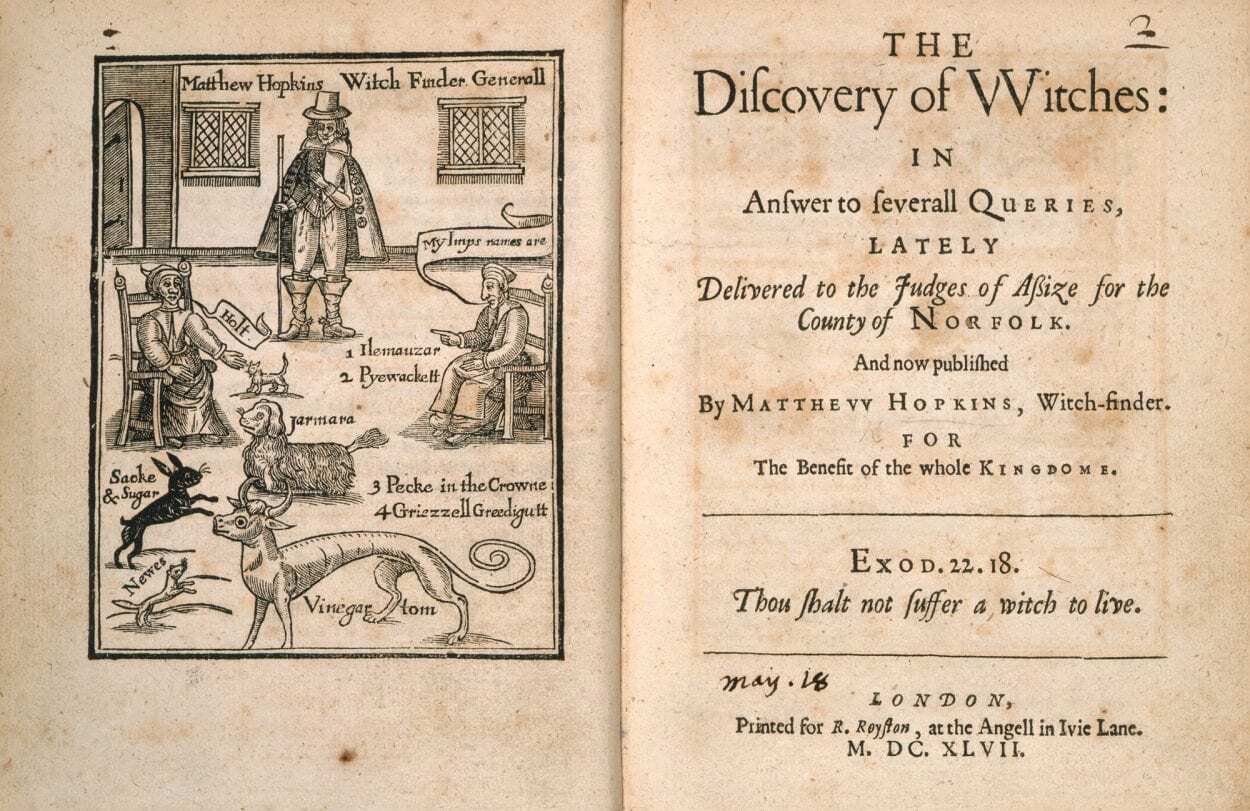

This proved to be a lucrative opportunity in terms of monetary gain, as Hopkins and his company were paid for their investigations, although Hopkins states in his book “The Discovery of Witches” that “his fees were to maintain his company with three horses”, and that he took “twenty shillings a town”. Historical records from Stowmarket shows that Hopkins actually charged the town £23, taking into account inflation would be around £3800 today.

Between the years of 1644 and 1646, Hopkins and his company are believed to be responsible for the execution of around 300 supposed witches and sent to the gallows more accused people than all the other witch-hunters in England of the previous 160 years.

By 1647, Hopkins and Stearne were questioned by justices of the assizes (the precursor to the English Crown Court) into their activities, but by the time the court resumed both Hopkins and Stearne retired from witch-hunting.

That same year, Hopkins published his book, “The Discovery of Witches” which was used as a manual for the trial and conviction of Margaret Jones in the Massachusetts Bay Colony on the east coast of America. Some of Hopkins’ methods were also employed during the Salem Witch Trials, in Salem, Massachusetts in 1692–93, resulting in hundreds of inhabitants being accused and 19 people executed.

Matthew Hopkins died at his home in Manningtree on the 12th August 1647 of pleural tuberculosis and was buried in the graveyard of the Church of St Mary at Mistley Heath. Within a year of the death of Hopkins, Stearne retired to his farm and wrote his own manual “A Confirmation and Discovery of Witchcraft” hoping to further profit from the infamous career path both men had undertaken that caused the death of hundreds of innocent souls.