The accepted date for the collapse of the Western Roman Empire was approximately 476 CE, when the last true Roman Emperor Romulus was overthrown by Odoacer, the Germanic leader who became the first Barbarian to rule Rome.

As the sun was setting on the west, in the east an enduring legacy carried on with the Byzantine Empire, otherwise known as the Eastern Roman Empire.

The Eastern Empire was spared many of the difficulties faced by the west, in part to an established centre of trade, greater financial resources and investment in defending its borders through both construction projects, diplomacy and tributes. The borders of the Empire evolved significantly over time, as it went through several cycles of decline and recovery.

Whilst never fully matching the glory of Imperial Rome in terms of territories in Byzantine control, the Eastern Empire would still grow to become one of the most powerful economic, cultural and military forces across Europe.

A New Hope

It wasn’t until the reign of Justinian I that thoughts turned to “renovatio imperii” – restoration of the Empire. The Byzantines still referred to their empire as “Imperium Romanum” (Roman Empire) and to themselves as “Roman”.

Justinian, known traditionally as “Justinian the Great” ruled the Byzantine Empire from 527 to 565 CE. His rule constitutes a distinct epoch in the history of the Later Roman empire that has left an enduring legacy today.

Dubbed “the emperor who never sleeps”, Justinian reformed the Roman tax and judicial systems, expanded the Empires borders across the Mediterranean and Africa, repelled invading nations and blossomed a golden age in art, literature and architecture. These successes were notably thanks to Justinian’s choosing of highly efficient, but unpopular advisers for state roles and the support of his wife Theodora.

But despite his successes, Justinian knew that his Empire was missing the very thing that makes it Roman… It was missing Rome….

The Ostrogoth Menace

With the fall of the Western Empire in 476 CE, Odoacer had gained the support of the remnants of the Roman Senate in Rome and was crowned the first King of Italy, forming the first Ostrogothic Kingdom.

His rule, although stained with conquest adopted the Roman administrative system and the law of the Empire remained as ruling the Roman population (though Goths were ruled under their own traditional laws).

And so, the Roman way of life continued, albeit a shadow of the glory that was Imperial Rome. But by the Reign of Theoderic the Great (493–526), the relationship with the Byzantine Empire and this fledgling Ostrogothic Kingdom begun to strain. Even the native Roman populous of Italy was feeling an increasing alienation of their cast from the Gothic regime.

The Gothic Wars

In the year 534 CE, the Byzantines under the command of General Belisarius had recovered the lost North African provinces taken by the Vandals from the Western Empire. Belisarius returned to Constantinople with the Vandals’ royal treasure to enjoy a triumph, while Africa was formally restored to imperial rule.

The Vandalic War produced an unexpectedly swift and decisive victory for the Roman Empire, and must certainly have encouraged Justinian in his ambition to recover more of the lost western provinces.

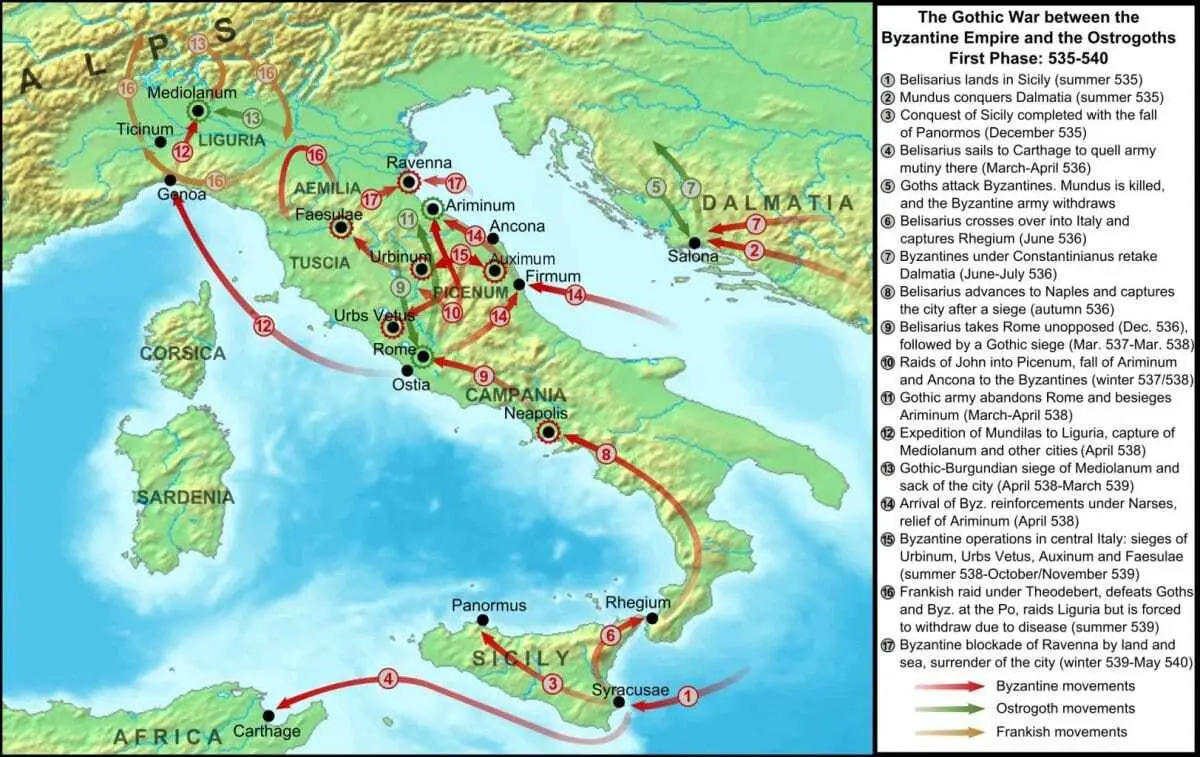

Utilising a dynastic dispute within the Ostrogothic kingdom, Justinian found an excuse for casus belli “an act or event that provokes or is used to justify war” and despatched the newly appointed commander in chief – stratēgos autokratōr Belisarius and Mundus Mundus, the magister militum per Illyricum in the year 535 CE.

Belisarius first landed in Sicily which saw little resistance to the Byzantine conquest. From there, preparations were made for an invasion of Italy by Sea. General Mundus, who commanded the forces in Illyricum led his forces into Dalmatia by land and took the capital, Salona.

The Dalmatian campaign resulted in heavy defeats on the Goths, but the Romans eventually withdrew. Not deterred by failure, Justinian sent a new magister militum per Illyricum named Constantianus to recover Dalmatia, the campaign resulted in a full retreat by gothic forces back to Italy.

In the late spring of 536 CE, Belisarius crossed with his invasion force of just 7,500 men into Italy and captured Rhegium. City after city began to fall until finally, in December of that year Rome was once again under Roman control. In light of the Gothic loses, the present King Theodahad was deposed and a new King, Vitiges was crowned who proceeded to place Rome under siege for a whole year.

With such a small Byzantine force to defend the walls, Belisarius could ill afford to engage in open field combat but did fight the entrenched Goths in sallies and minor engagements.

Reinforcements finally arrived from Constantinople in 537 CE, this allowed the Byzantines to go back on the offensive and push north through Italy. By 540 CE the Byzantine armies had marched on the Ostrogoth capital of Ravenna and captured the King.

Shortly before the taking of Ravenna, the Ostrogoths had offered to make Belisarius the Western Emperor but Belisarius feigned acceptance, before proclaiming the capture of Ravenna on arrival in the name of Emperor Justinian and the Eastern Roman Empire. Hearing of the Ostrogoths offer to crown Belisarius, Justinian had grown to mistrust his general and refused him the honour of a triumph on his return to Constantinople.

Even so, Belisarius was despatched shortly after to deal with the Persian conquest of Syria, a crucial province of the empire, where he repulsed renewed attacks. In his absence from Italy, the Ostrogoths had elected a new leader, Totila who was determined to restore the Gothic realm.

The Byzantine Empire had just been devastated by an outbreak of plague and was distracted by the new Roman-Persian Wars. Totalia took advantage of this period of instability that in part enabled his campaigning to see notable successes in the Gothic resurgence.

In 542 CE at the Battle of Faventia, 5000 Roman soldiers were annihilated. He saw victory again at the Battle of Mucellium when he defeated the pursuing superior Byzantine forces. He then marched the Gothic forces south recapturing large parts of Italy and drove the Romans out of Rome in his quest to reconquer Latium.

The Return of Belisarius

Taking advantage of a five-year truce in the East with the Persians, Belisarius was sent back to Italy with 200 ships and once again recovered Rome, but only briefly. He hastily rebuilt demolished sections of the defending walls and repelled another attack by Totalia’s forces.

Despite some small victories during his second campaign, overall victory proved unsuccessful, partly because of limited supplies and reinforcements from an empire which had been weakened by plague and partly, some historians believe to the jealously of an Emperor that considered Belisarius a potential threat to the crown and plotted his downfall from power. In 548-9 CE, Belisarius was relieved from service.

Narses the Eunuch

Another campaign in Italy was tasked to the nephew of Justinian, but in 550 CE he fell ill and shortly died. Command was passed to Narses, a eunuch and former general in the service of Belisarius who would prove to be another formidable commander in war.

Narses amassed a force of between 20,000 and 30,000 troops and made the long march along the coast of the Adriatic Sea to reach Italy. In support was a fleet of ships that fought the Ostrogothic navy at the Battle of Sena Gallica to victory.

Narses saw success at the Battle of Taginae (also known as the Battle of Busta Gallorum) when in 552 CE, his forces broke the power of the Ostrogoths and Totalia died in the ensuing battle.

He now marched on Rome, and after a short siege the city was once again Roman.

From here Narses coordinated the elimination of Ostrogothic resistance left in Italy who finally succumbed at the Battle of Mons Lactarius. Italy, Rome and many former provinces were now finally part of an integrated Roman Empire.

The Aftermath

The Gothic War drained the life and the finances of the Eastern Roman Empire in Justinian’s folly of a restored empire. He had increased the territories governed by the Byzantines by almost 45% during his reign, but at the cost of almost crippling the Empire and leaving the borders weak and vulnerable to invaders from all sides.

Rome itself, was left in a state of total disrepair — near-abandoned and desolate with much of its lower-lying parts turning to marsh. Justinian tried to grant Rome subsidies for the maintenance of public buildings, aqueducts and bridges — though, being mostly drawn from an Italy dramatically impoverished by the recent wars, these were not always sufficient.

The Senate of Rome was theoretically restored, but was second to the supervision of the urban prefect and Byzantine authorities in Ravenna. Local power in Rome eventually devolved to the Pope and, over the next few decades, both much of the remaining possessions of the senatorial aristocracy and the local Byzantine administration in Rome were absorbed by the Church.

Three years after the death of Justinian, the mainland Italian territories fell into the hands of a Germanic tribe, the Lombards, leaving the Exarchate of Ravenna, a band of territory that stretched across central Italy to the Tyrrhenian Sea and south to Naples, along with parts of southern Italy, as the only remaining Imperial holdings in the country.

Whilst the borders would change many times over the centuries, the Byzantine Empire carried on as a beacon of civilisation, art and culture, that arguably surpassed even Imperial Rome. Almost 900 years later, with the invading Turks on the doorstep of Contantinople, on May 29, 1453 CE, the sun finally set for the Eastern Roman Empire.