After spotting a curious pattern in scientific papers – they described exoplanets as being cooler than expected – Cornell University astronomers have improved a mathematical model to accurately gauge the temperatures of planets from solar systems hundreds of light-years away.

This new model allows scientists to gather data on an exoplanet’s molecular chemistry and gain insight on the cosmos’ planetary beginnings, according to research published April 23 in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Nikole Lewis, assistant professor of astronomy and the deputy director of the Carl Sagan Institute (CSI), had noticed that over the past five years, scientific papers described exoplanets as being much cooler than predicted by theoretical models.

“It seemed to be a trend – a new phenomenon,” Lewis said. “The exoplanets were consistently colder than scientists would expect.”

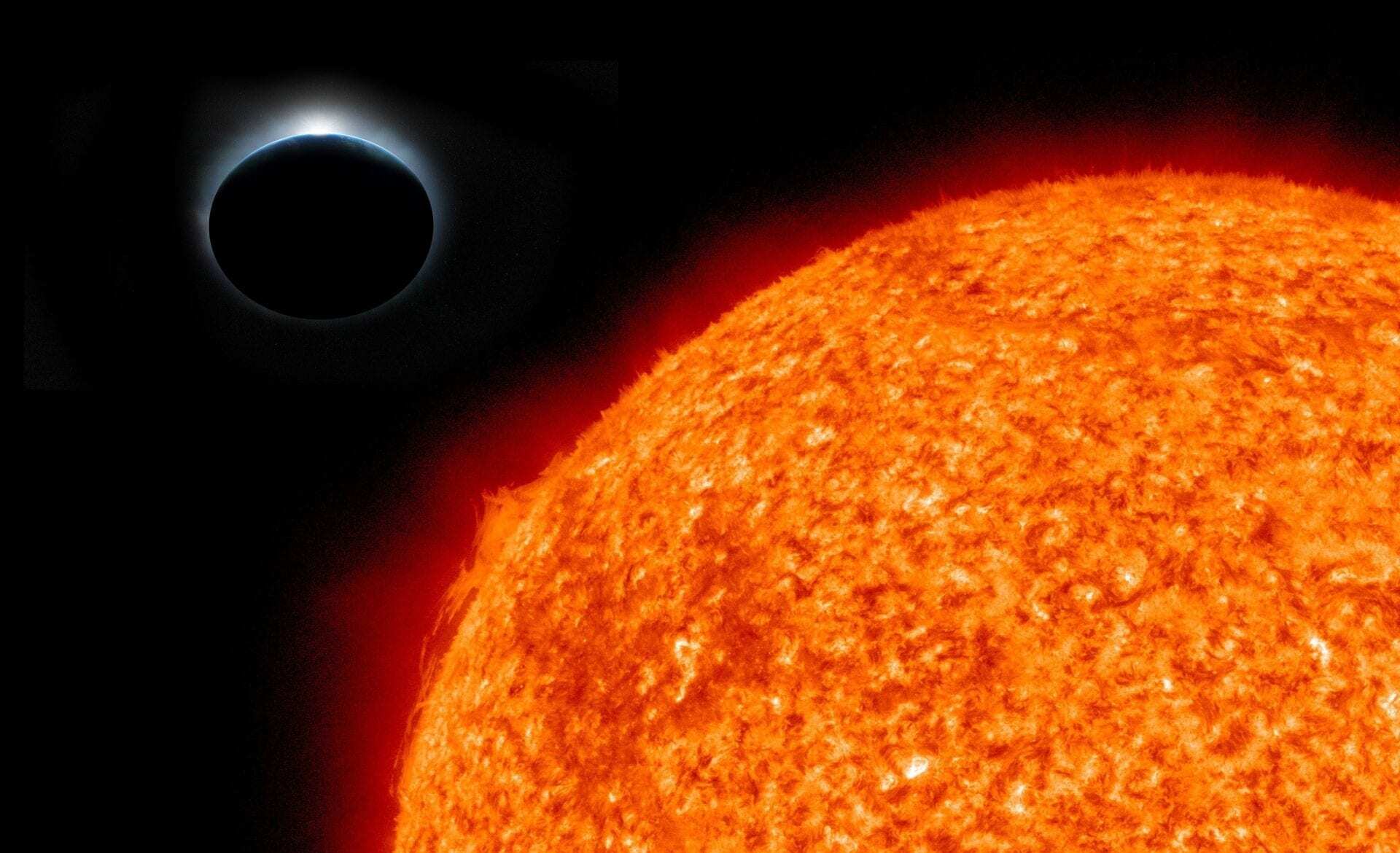

To date, astronomers have detected more than 4,100 exoplanets. Among them are “hot Jupiters,” a common type of gaseous giant that always orbits close to its host star. Thanks to the star’s overwhelming gravity, hot Jupiters always have one side facing their star, a situation known as “tidal locking.”

Therefore, as one side of the hot Jupiter broils, the planet’s far side features much cooler temperatures. In fact, the hot side of the tidally locked exoplanet bulges like a balloon, shaping it like an egg.

From a distance of tens to hundreds of light-years away, astronomers have traditionally seen the exoplanet’s temperature as homogenous – averaging the temperature – making it seem much colder than physics would dictate.

Temperatures on exoplanets – particularly hot Jupiters – can vary by thousands of degrees, according to lead author Ryan MacDonald, a researcher at CSI, who said wide-ranging temperatures can promote radically different chemistry on different sides of the planets.

After poring over exoplanet scientific papers, Lewis, MacDonald and research associate Jayesh Goyal solved the mystery of seemingly cooler temperatures: Astronomers’ math was wrong.

“When you treat a planet in only one dimension, you see a planet’s properties – such as temperature – incorrectly,” Lewis said. “You end up with biases. We knew the 1,000-degree differences were not correct, but we didn’t have a better tool. Now, we do.”

Astronomers now may confidently size up exoplanets’ molecules.

“We won’t be able to travel to these exoplanets any time in the next few centuries, so scientists must rely on models,” MacDonald said, explaining that when the next generation of space telescopes get launched starting in 2021, the detail of exoplanet datasets will have improved to the point where scientists can test the predictions of these three-dimensional models.

“We thought we would have to wait for the new space telescopes to launch,” said MacDonald, “but our new models suggest the data we already have – from the Hubble Space Telescope – can already provide valuable clues.”

With updated models that incorporate current exoplanet data, astronomers can tease out the temperatures on all sides of an exoplanet and better determine the planet’s chemical composition.

Said MacDonald: “When these next-generation space telescopes go up, it will be fascinating to know what these planets are really like.”