Studying the inner ear of apes and humans could uncover new information on our species’ evolutionary relationships.

Humans, gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans and gibbons all belong to a group known as the hominoids. This ‘superfamily’ also includes the immediate ancestors and close relatives of these species, but in many instances, the evolutionary relationships between these extinct ape species remain controversial. The new findings suggest that looking at the structure (or morphology) of the inner ears across hominoids as a whole could go some way to resolving this.

“Reconstructing the evolutionary history of apes and humans and determining the morphology of the last common ancestor from which they evolved are challenging tasks,” explains lead author Alessandro Urciuoli, a researcher at the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP) in Barcelona, Spain. “While DNA can help evolutionary biologists work out how living species are related to one another, fossils are typically the principle source of information for extinct species, although they must be used with caution.”

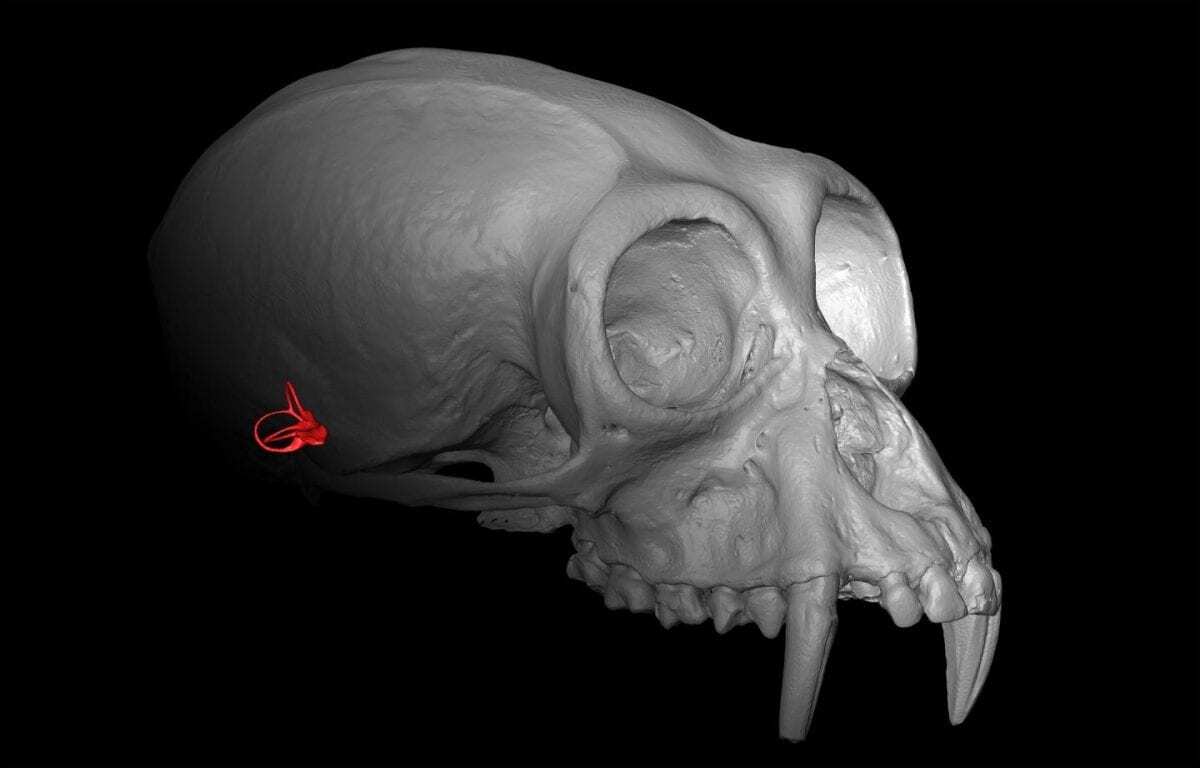

The bony cavity that houses the inner ear, which is involved in balance and hearing and is fairly common in the fossil record, has proven useful for tracing the evolution of certain groups of mammals. But until now, no studies have explored whether this structure could provide insights into the evolutionary relatedness among living and extinct hominoids.

To address this, Urciuoli and his team used a 3D imaging technique to capture the complex shapes of the inner ear cavities of 27 species of monkeys and apes, including humans and the extinct ape Oreopithecus and fossil hominin Australopithecus. Their results confirmed that the shape of these structures most closely reflected the evolutionary relationships between the species and not, for example, how the animals moved.

The team next identified features of these bony chambers that were shared among several hominoid groups, and estimated how the inner ears of these groups’ ancestors might have looked. Their findings for Australopithecus were consistent with this species being the most closely related to modern humans than other apes, while those for Oreopithecus supported the view that this was a much older species of ape related in some respects with other apes still alive today.

“Our work provides a testable hypothesis about inner ear evolution in apes and humans that should be subjected to further scrutiny based on the analysis of additional fossils, particularly for great apes that existed during the Miocene,” says senior author David Alba, Director of the ICP. The Miocene period, which extends from about 23 to five million years ago, is when the evolutionary path to hominoids became distinct.

Urciuoli adds that, in years to come, disentangling the kinship relationships between Miocene apes will be essential for improving our understanding of the evolution of hominoids, including humans and our closest living relatives, the chimpanzee and bonobo.

Header Image – A virtual 3D model of a gibbon skull with part of the inner ear highlighted in red. Credit : Alessandro Urciuoli (CC BY 4.0)