A new Jurassic non-avian theropod dinosaur from 163 million-year-old fossil deposits in northeastern China provides new information regarding the incredible richness of evolutionary experimentation that characterized the origin of flight in the Dinosauria.

Drs. WANG Min, Jingmai K. O’Connor, XU Xing, and ZHOU Zhonghe from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences described and analyzed the well-preserved skeleton of a new species of Jurassic scansoriopterygid dinosaur with associated feathers and membranous tissues. Their findings were published in Nature.

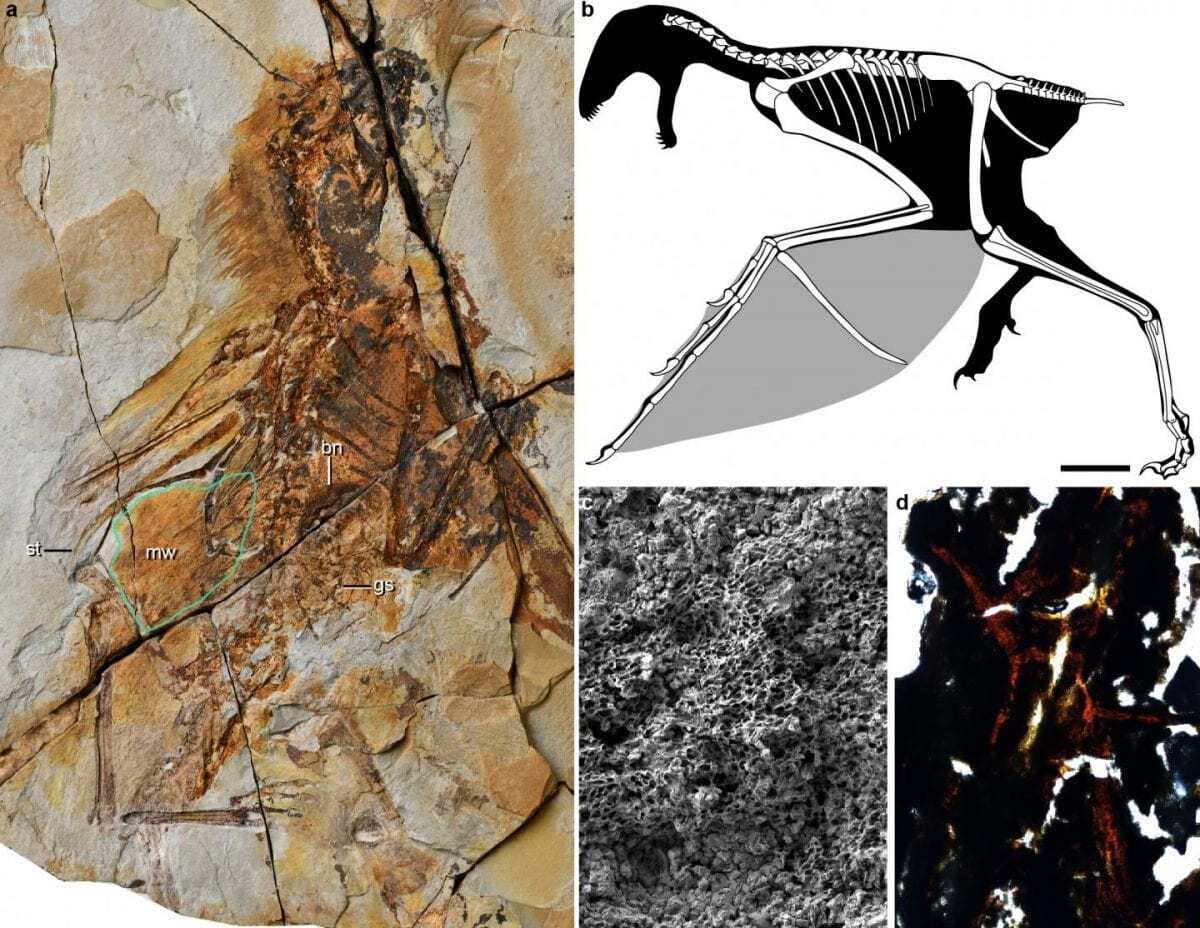

The new species, named Ambopteryx longibrachium, belongs to the Scansoriopterygidae, one of the most bizarre groups of non-avian theropods. The Scansoriopterygidae differ from other theropods in their body proportions, particularly in the proportions of the forelimb, which supports a bizarre wing structure first recognized in a close relative of Ambopteryx, Yi qi.

Unlike other flying dinosaurs, namely birds, these two species have membranous wings supported by a rod-like wrist bone that is not found in any other dinosaur (but is present in pterosaurs and flying squirrels).

Until the discovery of Yi qi in 2015, such a flight apparatus was completely unknown among theropod dinosaurs. Due to incomplete preservation in the holotype and only known specimen of Yi qi, the veracity of these structures and their exact function remained hotly debated.

As the most completely preserved specimen to date, Ambopteryx preserves membranous wings and the rod-like wrist, supporting the widespread existence of these wing structures in the Scansoriopterygidae.

WANG and his colleagues investigated the ecomorphospace disparity of Ambopteryx relative to other non-avian coelurosaurians and Mesozoic birds. The results showed dramatic changes in wing architecture evolution between the Scansoriopterygidae and the avian lineage, as the two clades diverged and underwent very different evolutionary paths to achieving flight.

Interestingly, forelimb elongation, an important characteristic of flying dinosaurs, was achieved in scansoriopterygids primarily through elongation of the humerus and ulna, whereas the metacarpals were elongated in non-scansoriopterygid dinosaurs including Microraptor and birds.

In scansoriopterygids, the presence of an elongated manual digit III and the rod-like wrist probably compensated for the relatively short metacarpals and provided the main support for the membranous wings. In contrast, selection for relatively elongated metacarpals in most birdlike dinosaurs was likely driven by the need for increased area for the attachment of the flight feathers, which created the wing surface in Microraptor and birds.

The co-occurrence of short metacarpals with membranous wings, versus long metacarpals and feathered wings, exhibits how the evolution of these two significantly different flight strategies affected the overall forelimb structure. So far, all known scansoriopterygids are from the Late Jurassic and their unique membranous wing structure did not survive into the Cretaceous.

This suggests that this wing structure represents a short-lived and unsuccessful attempt to fly. In contrast, feathered wings, first documented in Late Jurassic non-avian dinosaurs, were further refined through the evolution of numerous skeletal and soft tissue modifications, giving rise to at least two additional independent origins of dinosaur flight and ultimately leading to the current success of modern birds.

CHINESE ACADEMY OF SCIENCES HEADQUARTERS

Header Image – Fossil; b. restoration, scale bar equal 10 mm; c. melanosomes of the membranous wing (mw); d. histology of the bony stomach content (bn). st, styliform element; gs, gastroliths. Credit : WANG Min