Most of Earth’s essential elements for life — including most of the carbon and nitrogen in you — probably came from another planet.

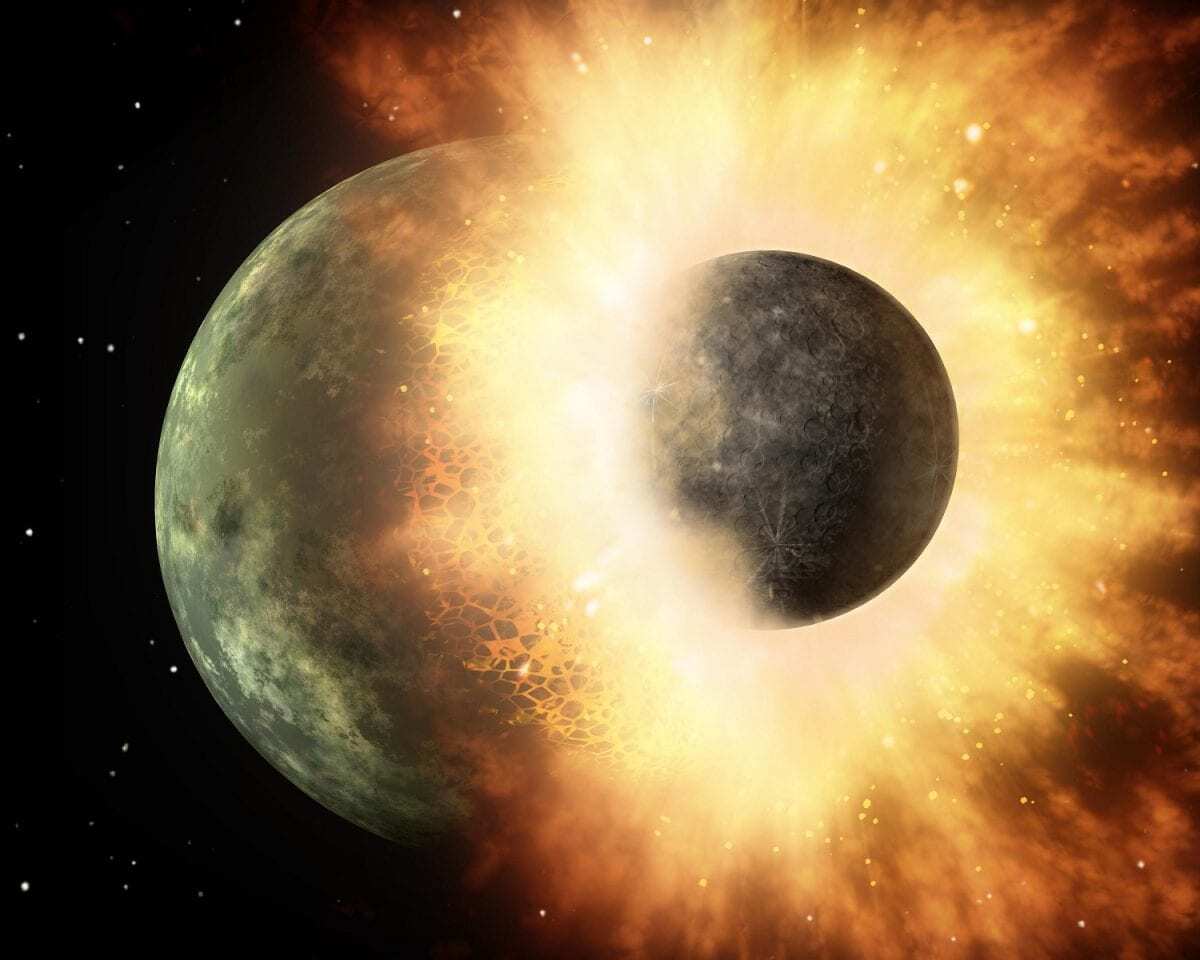

Earth most likely received the bulk of its carbon, nitrogen and other life-essential volatile elements from the planetary collision that created the moon more than 4.4 billion years ago, according to a new study by Rice University petrologists in the journal Science Advances.

“From the study of primitive meteorites, scientists have long known that Earth and other rocky planets in the inner solar system are volatile-depleted,” said study co-author Rajdeep Dasgupta. “But the timing and mechanism of volatile delivery has been hotly debated. Ours is the first scenario that can explain the timing and delivery in a way that is consistent with all of the geochemical evidence.”

The evidence was compiled from a combination of high-temperature, high-pressure experiments in Dasgupta’s lab, which specializes in studying geochemical reactions that take place deep within a planet under intense heat and pressure.

In a series of experiments, study lead author and graduate student Damanveer Grewal gathered evidence to test a long-standing theory that Earth’s volatiles arrived from a collision with an embryonic planet that had a sulfur-rich core.

The sulfur content of the donor planet’s core matters because of the puzzling array of experimental evidence about the carbon, nitrogen and sulfur that exist in all parts of the Earth other than the core.

“The core doesn’t interact with the rest of Earth, but everything above it, the mantle, the crust, the hydrosphere and the atmosphere, are all connected,” Grewal said. “Material cycles between them.”

One long-standing idea about how Earth received its volatiles was the “late veneer” theory that volatile-rich meteorites, leftover chunks of primordial matter from the outer solar system, arrived after Earth’s core formed. And while the isotopic signatures of Earth’s volatiles match these primordial objects, known as carbonaceous chondrites, the elemental ratio of carbon to nitrogen is off. Earth’s non-core material, which geologists call the bulk silicate Earth, has about 40 parts carbon to each part nitrogen, approximately twice the 20-1 ratio seen in carbonaceous chondrites.

Grewal’s experiments, which simulated the high pressures and temperatures during core formation, tested the idea that a sulfur-rich planetary core might exclude carbon or nitrogen, or both, leaving much larger fractions of those elements in the bulk silicate as compared to Earth. In a series of tests at a range of temperatures and pressure, Grewal examined how much carbon and nitrogen made it into the core in three scenarios: no sulfur, 10 percent sulfur and 25 percent sulfur.

“Nitrogen was largely unaffected,” he said. “It remained soluble in the alloys relative to silicates, and only began to be excluded from the core under the highest sulfur concentration.”

Carbon, by contrast, was considerably less soluble in alloys with intermediate sulfur concentrations, and sulfur-rich alloys took up about 10 times less carbon by weight than sulfur-free alloys.

Using this information, along with the known ratios and concentrations of elements both on Earth and in non-terrestrial bodies, Dasgupta, Grewal and Rice postdoctoral researcher Chenguang Sun designed a computer simulation to find the most likely scenario that produced Earth’s volatiles. Finding the answer involved varying the starting conditions, running approximately 1 billion scenarios and comparing them against the known conditions in the solar system today.

“What we found is that all the evidence — isotopic signatures, the carbon-nitrogen ratio and the overall amounts of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur in the bulk silicate Earth — are consistent with a moon-forming impact involving a volatile-bearing, Mars-sized planet with a sulfur-rich core,” Grewal said.

Dasgupta, the principal investigator on a NASA-funded effort called CLEVER Planets that is exploring how life-essential elements might come together on distant rocky planets, said better understanding the origin of Earth’s life-essential elements has implications beyond our solar system.

“This study suggests that a rocky, Earth-like planet gets more chances to acquire life-essential elements if it forms and grows from giant impacts with planets that have sampled different building blocks, perhaps from different parts of a protoplanetary disk,” Dasgupta said.

“This removes some boundary conditions,” he said. “It shows that life-essential volatiles can arrive at the surface layers of a planet, even if they were produced on planetary bodies that underwent core formation under very different conditions.”

Dasgupta said it does not appear that Earth’s bulk silicate, on its own, could have attained the life-essential volatile budgets that produced our biosphere, atmosphere and hydrosphere.

“That means we can broaden our search for pathways that lead to volatile elements coming together on a planet to support life as we know it.”

Header Image Credit : NASA/JPL-Caltech