A hillfort or hill fortification is a type of earthworks used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage.

The fortification usually follows the contours of a hill, consisting of one or more lines of earthworks, with stockades or defensive walls, and external ditches.

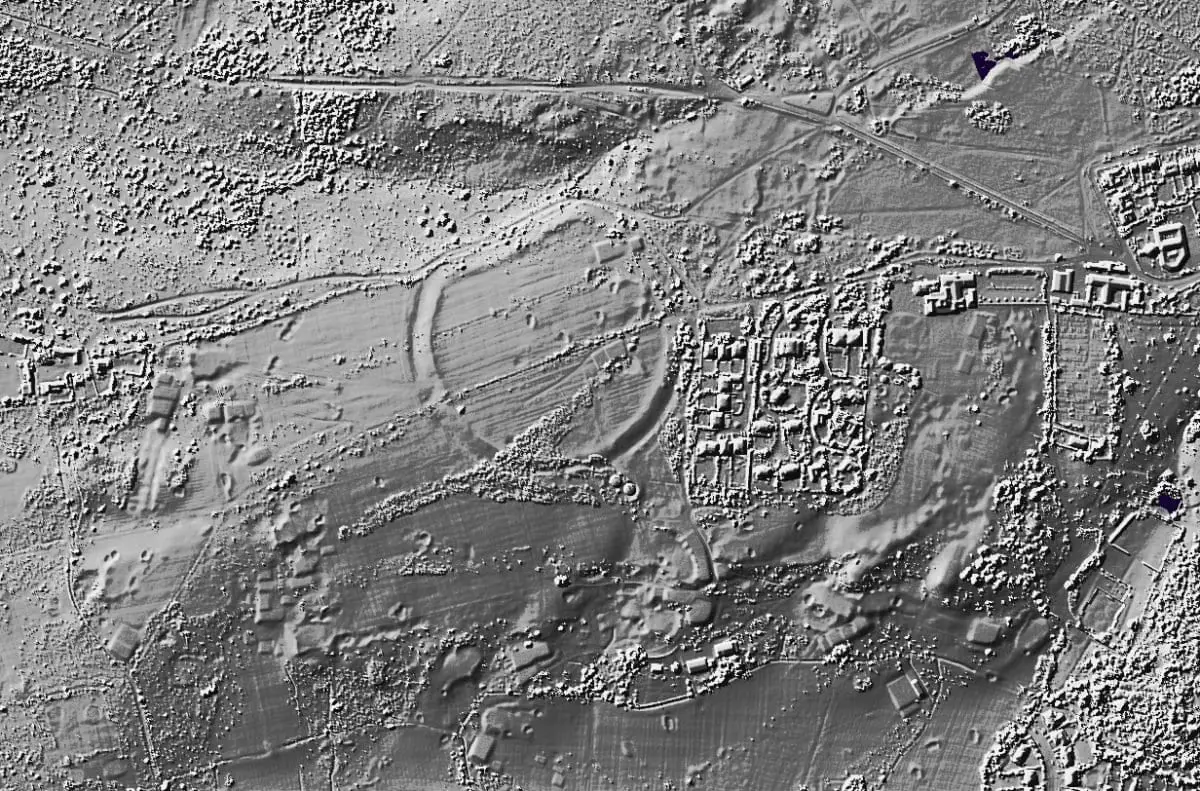

Loughton Camp Iron Age Fort

Loughton Camp is an Iron Age fort in Epping Forest NE London and built around 500 BC.

The camp’s earthworks cover 10 acres and would originally have been 3 metres high with outer ditches dug to a depth of also 3 metres. They would have been built by hand and wooden or bone tools used to scrape the soil.

Built at one of the highest points in Epping Forest, the camp would have had strategic views that has led to the theory of being a look-out post for the Tinovantes in defence against their neighbours, the Catuvellauni.

The most accepted theory is that they were used as animal folds in times of attack from other tribes.

The Hill Fort was ‘discovered’ by Mr Benjamin Harris Cowper in 1872 and excavated in 1881 by Augustus Pitt-Rivers (Britain’s first Inspector of Ancient Monuments – charged with cataloguing archaeological sites and protecting them from destruction).

Ambresbury Banks – Iron Age Fort

Ambresbury Banks is an Iron Age Fort in Epping Forest NE London and built around 500 BC.

The forts earthworks cover 9 acres and would originally have been 3 metres high with outer ditches dug to a depth of also 3 metres.

A re-cutting of the forts ditches in the first century AD may represent re-occupation in the pre-conquest years, however, no later occupation has been noted from later dates.

Archaeologists have explored the site on 9 occasions, the first being in 1881 by Augustus Pitt-Rivers (Britain’s first Inspector of Ancient Monuments – charged with cataloguing archaeological sites and protecting them from destruction).

The area within and around the fort is now completely wooded, but in the Iron Age period it would have been cleared of trees for agriculture and commanding views of the landscape. (Suggested by evidence of Wild Service trees which are an indicator of regrown forest).

Wimbledon Iron Age Fort (Caesar’s Camp)

On Wimbledon Common remains a circular contour Iron Age Fort that covers an area of around 11 acres.

The earthworks date from around the 3rd century BC, with further traces of Belgic (Late Iron Age) occupation.

The fort, also named Caesar’s Camp is situated on a spur that overlooks the land to the west across Beverly Brook in Wimbledon Common just south of Putney.

The ramparts were slighted in 1875 by John Samuel Sawbridge-Erle-Drax who had planned to develop and build on the monument. Thankfully site plans had been drawn prior that showed a counterscarp bank on all sides.

Only on the NNW side, where the ground slopes steeply down to a boggy area is there any significant natural defence surviving today.

There are no signs of the entrance in the NW corner, nor of that in the south side shown but remains of a counterscarp bank still survive in the southern half.

Grim’s Ditch

Grim’s Ditch (also known as Grim’s Dyke) is an ancient earthwork in North West London.

This ditch once stretched through Harrow for some six miles from Cuckoo Hill, Pinner to Pear Wood, Stanmore, but now only parts remain with limited access.

Grim is the Saxon word for devil or goblin and was given to various linear earthworks similar to the one in Harrow and as such it is likely that the earthworks name was derived from this time.

Little conclusive evidence has been found to accurately date the construction of the bank and ditch. However, archaeological excavations at Grim’s Dyke Hotel carried out in 1979 found a 1st century, or slightly earlier, fire hearth. Other discoveries include Iron Age and Belgic Pottery found during excavations of the Montesole Playing Fields the earthwork runs through in 1957.

One theory for its construction was a defence against the Romans by the Catuvellauni tribe, but there lacks any archaeological evidence or historical context to support this.

The ditch is too small to have any military application, but archaeologists believe that they may have served to demarcate territory.

St Ann’s Hill (Iron Age Hill Fort)

St Ann’s Hill Hillfort (Eldebury or Oldbury Hill) is a univallate hill fort enclosing around 12 acres that dates mostly to the middle Iron Age.

Finds date from the Mesolithic and Bronze Age through to the Roman period which suggests the elevated position (69 metres above sea level) offered opportunistic commanding views of the local landscape.

A small trench in the interior identified 53 prehistoric features with post-holes indicating three or more building phases.

Uphall Camp (Iron Age Fort)

Uphall Camp is the site of an Iron Age fort from around 150-200 BC and a later Roman settlement that is now covered by modern development in Ilford.

Situated above the left bank of the River Roding, the 48 acre fortification was around 550 metres long and between 400-500 metres wide.

Surrounded by defensive ditches and palisades, Uphall camp contains two groupings of structures, perhaps representing two groups of people who existed on site at different periods.

Excavations suggest that there was several round buildings with gullies in addition to houses and some sort of ‘barn’.

Caesar’s Camp Keston (Iron Age Fort)

Caesar’s Camp is a multivallate hillfort containing earthworks and below-ground remains. It is situated near the summit of a hill in Holwood Park, east of Keston Common and covers an area of about 43 acres.

Earthworks include two eastern banks and ditches about 40m wide, with in places a counterscarp bank. The ramparts or banks are about 3m above the original ground surface.

The site was first documented by Thomas Milne in the late 18th century, followed by excavations in 1956-7 that excavated the interior of the fort. Mesolithic flints and Iron Age pottery were recovered and evidence indicated that the hillfort was built in about 200 BC.

The London History Group is a project aimed at documenting and recording the less known historical sites from across London. The project is run by community archaeologists and historians who are working with an active social audience to investigate the sites and create a lasting online directory. – FIND OUT MORE