A University of Bristol-led study has revealed new details about dinosaur feathers and enabled scientists to further refine what is potentially the most accurate depiction of any dinosaur species to date.

Birds are the direct descendants of a group of feathered, carnivorous dinosaurs that, along with true birds, are referred to as paravians – examples of which include the infamous Velociraptor.

Researchers examined, at high resolution, an exceptionally-preserved fossil of the crow-sized paravian dinosaur Anchiornis – comparing its fossilised feathers to those of other dinosaurs and extinct birds.

The feathers around the body of Anchiornis, known as contour feathers, revealed a newly-described, extinct, primitive feather form consisting of a short quill with long, independent, flexible barbs erupting from the quill at low angles to form two vanes and a forked feather shape.

The observations were made possible by decay processes that separated some of these feathers from the body prior to burial and fossilisation, making their structure easier to interpret.

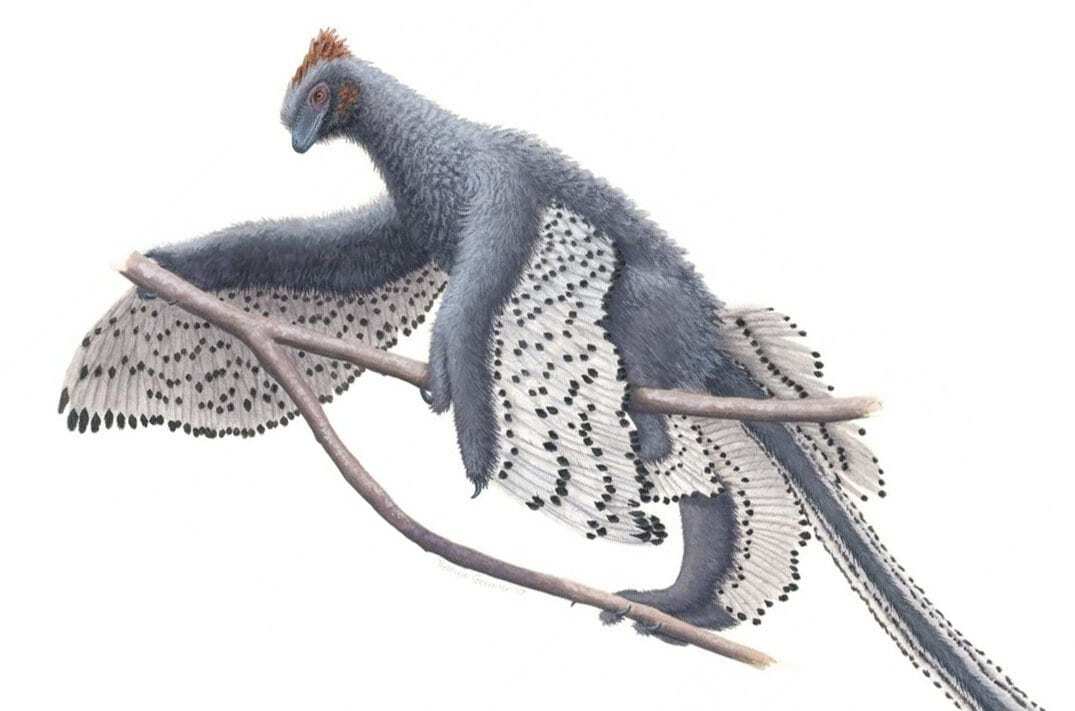

Such feathers would have given Anchiornis a fluffy appearance relative to the streamlined bodies of modern flying birds, whose feathers have tightly-zipped vanes forming continuous surfaces. Anchiornis‘s unzipped feathers might have affected the animal’s ability to control its temperature and repel water, possibly being less effective than the vanes of most modern feathers. This shaggy plumage would also have increased drag when Anchiornis glided.

Additionally, the feathers on the wing of Anchiornis lack the aerodynamic, asymmetrical vanes of modern flight feathers, and the new research shows that these vanes were also not tightly-zipped compared to modern flight feathers. This would have hindered the feather’s ability to form a lift surface. To compensate, paravians like Anchiornis packed multiple rows of long feathers into the wing, unlike modern birds, where most of the wing surface is formed by just one row of feathers.

Furthermore, Anchiornis and other paravians had four wings, with long feathers on the legs in addition to the arms, as well as elongated feathers forming a fringe around the tail. This increase in surface-area likely allowed for gliding before the evolution of powered flight.

To assist in reconstructing the updated look of Anchiornis, scientific illustrator Rebecca Gelernter worked with Evan Saitta and Dr Jakob Vinther, from the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences and School of Biological Sciences, to draw the animal as it was in life.

The new piece represents a radical shift in dinosaur depictions and incorporates previous research.

The color patterns for Anchiornis are known from fossilised pigment studies, the outline of the flesh of the animal has been constructed by examining fossils under laser fluorescence, and previous work has described the multi-tiered layering of the wing feathers.

Evan Saitta said: “The novel aspects of the wing and contour feathers, as well as fully-feathered hands and feet, are added to the depiction.

“Most provocatively, Anchiornis is presented in this artwork climbing in the manner of hoatzin chicks, the only living bird whose juveniles retain a relic of their dinosaurian past, a functional claw.

“This contrasts much previous art that places paravians perched on top of branches like modern birds.

“However, such perching is unlikely given the lack of a reversed toe as in modern perching birds and climbing is consistent with the well-developed arms and claws in paravians.

“Overall, our study provides some new insight into the appearance of dinosaurs, their behavior and physiology, and the evolution of feathers, birds, and powered flight.”

Rebecca Gelernter added: “Paleoart is a weird blend of strict anatomical drawing, wildlife art, and speculative biology. The goal is to depict extinct animals and plants as accurately as possible given the available data and knowledge of the subject’s closest living relatives.

“As a result of this study and other recent work, this is now possible to an unprecedented degree for Anchiornis. It’s easy to see it as a living animal with complex behaviours, not just a flattened fossil.

“It’s really exciting to be able to work with the scientists at the forefront of these discoveries, and to show others what we believe these fluffy, toothy almost-birds looked like as they went about their Jurassic business.”

Header Image: A new depiction of Anchiornis and its contour feather. CREDIT Rebecca Gelernter