The ancient Romans were famous for their advanced water supply. But the drinking water in the pipelines was probably poisoned on a scale that may have led to daily problems with vomiting, diarrhoea, and liver and kidney damage. This is the finding of analyses of water pipe from Pompeii.

– The concentrations were high and were definitely problematic for the ancient Romans. Their drinking water must have been decidedly hazardous to health.

This is what a chemist from University of Southern Denmark reveals: Kaare Lund Rasmussen, a specialist in archaeological chemistry. He analysed a piece of water pipe from Pompeii, and the result surprised both him and his fellow scientists. The pipes contained high levels of the toxic chemical element, antimony.

The result has been published in the journal Toxicology Letters.

Romans poisoned themselves

For many years, archaeologists have believed that the Romans’ water pipes were problematic when it came to public health. After all, they were made of lead: a heavy metal that accumulates in the body and eventually shows up as damage to the nervous system and organs. Lead is also very harmful to children. So there has been a long-lived thesis that the Romans poisoned themselves to a point of ruin through their drinking water.

– However, this thesis is not always tenable. A lead pipe gets calcified rather quickly, thereby preventing the lead from getting into the drinking water. In other words, there were only short periods when the drinking water was poisoned by lead: for example, when the pipes were laid or when they were repaired: assuming, of course, that there was lime in the water, which there usually was, says Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

Instead, he believes that the Romans’ drinking water may have been poisoned by the chemical element, antimony, which was found mixed with the lead.

Advanced equipment at SDU

Unlike lead, antimony is acutely toxic. In other words, you react quickly after drinking poisoned water. The element is particularly irritating to the bowels, and the reactions are excessive vomiting and diarrhoea that can lead to dehydration. In severe cases it can also affect the liver and kidneys and, in the worst-case scenario, can cause cardiac arrest.

This new knowledge of alarmingly high concentrations of antimony comes from a piece of water pipe found in Pompeii.

– Or, more precisely, a small metal fragment of 40 mg, which I obtained from my French colleague, Professor Philippe Charlier of the Max Fourestier Hospital, who asked if I would attempt to analyse it. The fact is that we have some particularly advanced equipment at SDU, which enables us to detect chemical elements in a sample and, ever more importantly, to measure where they occur in large concentrations.

Volcano made it even worse

Kaare Lund Rasmussen underlines that he only analysed this one little fragment of water pipe from Pompeii. It will take several analyses before we can get a more precise picture of the extent, to which Roman public health was affected.

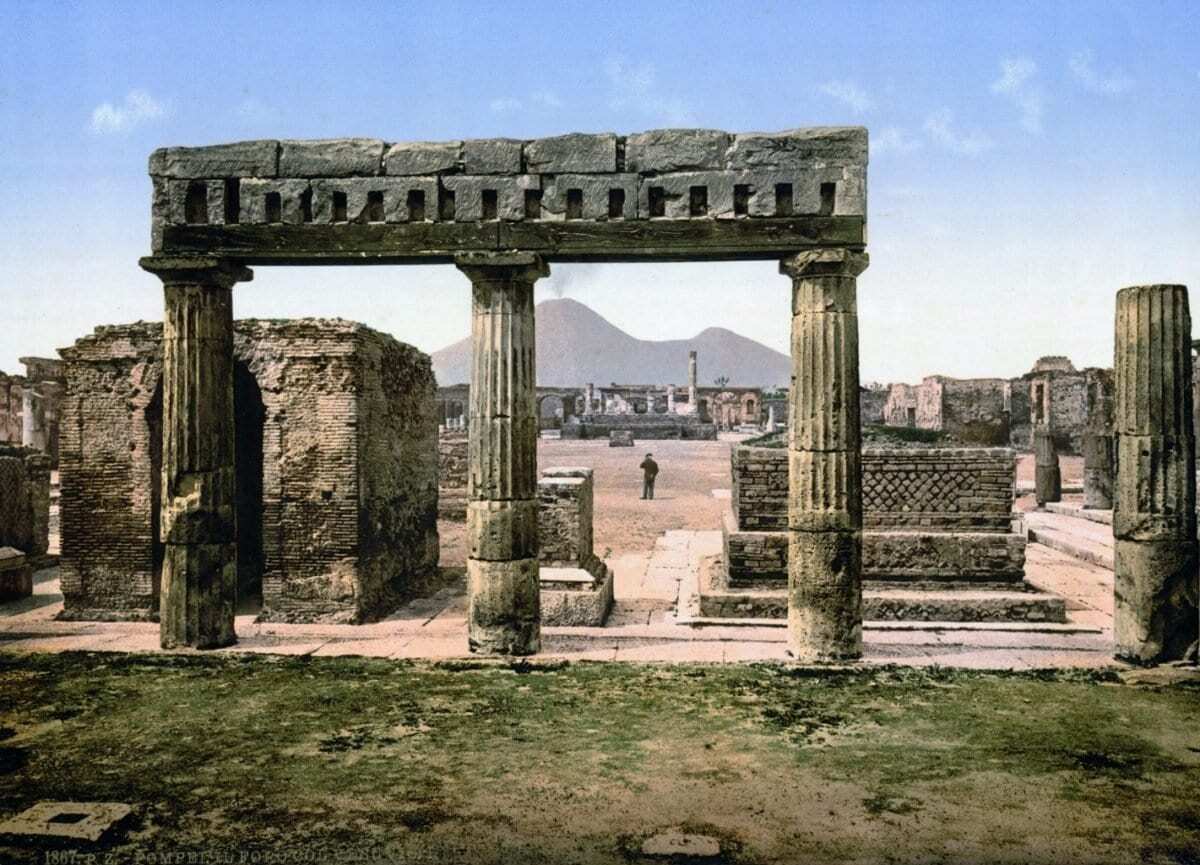

But there is no question that the drinking water in Pompeii contained alarming concentrations of antimony, and that the concentration was even higher than in other parts of the Roman Empire, because Pompeii was located in the vicinity of the volcano, Mount Vesuvius. Antimony also occurs naturally in groundwater near volcanoes.

This is what the researchers did

The measurements were conducted on a Bruker 820 Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer.

The sample was dissolved in concentrated nitric acid. 2 mL of the dissolved sample was transferred to a loop and injected as an aerosol in a stream of argon gas which was heated to 6000 degrees C by the plasma.

All the elements in the sample were ionized and transferred as an ion beam into the mass spectrometer. By comparing the measurements against measurements on a known standard the concentration of each element is determined.

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN DENMARK

Header Image – CC Public Domain