Cleopatra VII Philopator, commonly known simply as Cleopatra, ruled over Egypt during the century preceding the birth of Christ. By Robyn Antanovskii

Over the next two thousand years and counting, she would be renowned for her outstanding physical beauty, inspiring innumerable works of art depicting her as an alluring temptress, and spawning countless modern beauty parlours in her name.

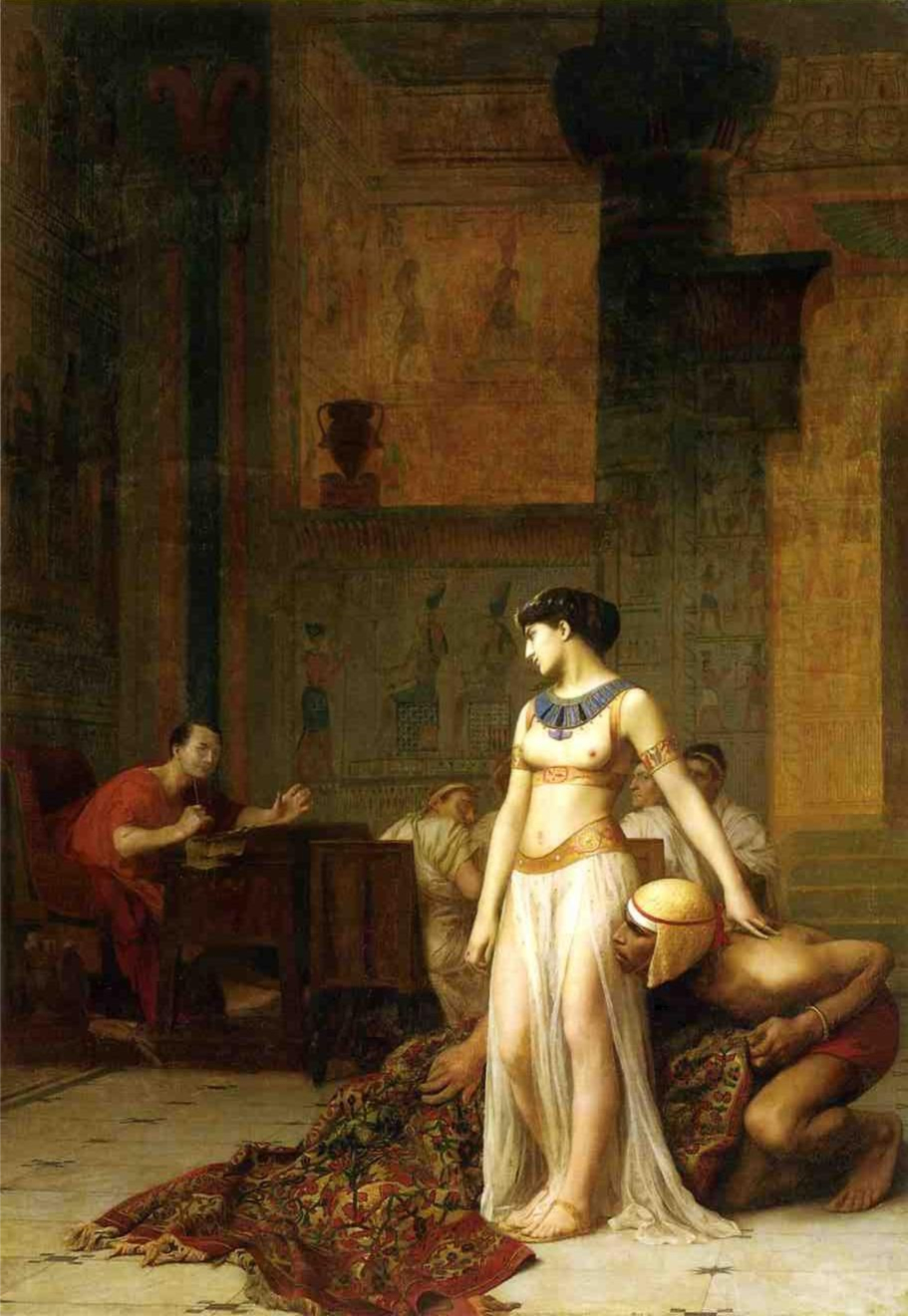

No doubt the legend of her beauty is based in part on her famous seduction of both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, both powerful Roman leaders. But what did she really look like? Is there any solid basis to the claims of unparalleled physical beauty? Let’s have a look at what the historical and archaeological evidence tells us.

Writing another two centuries after Cleopatra’s reign, the Roman historian Cassius Dio describes Cleopatra as “a woman of surpassing beauty” who was “brilliant to look upon.” Yet Greek historian Plutarch, writing more than a century earlier than Dio, maintains that “her beauty… was in itself not altogether incomparable, nor such as to strike those who saw her.” As neither are contemporary accounts, there is no good reason to believe one over the other, or even to believe either of them at all.

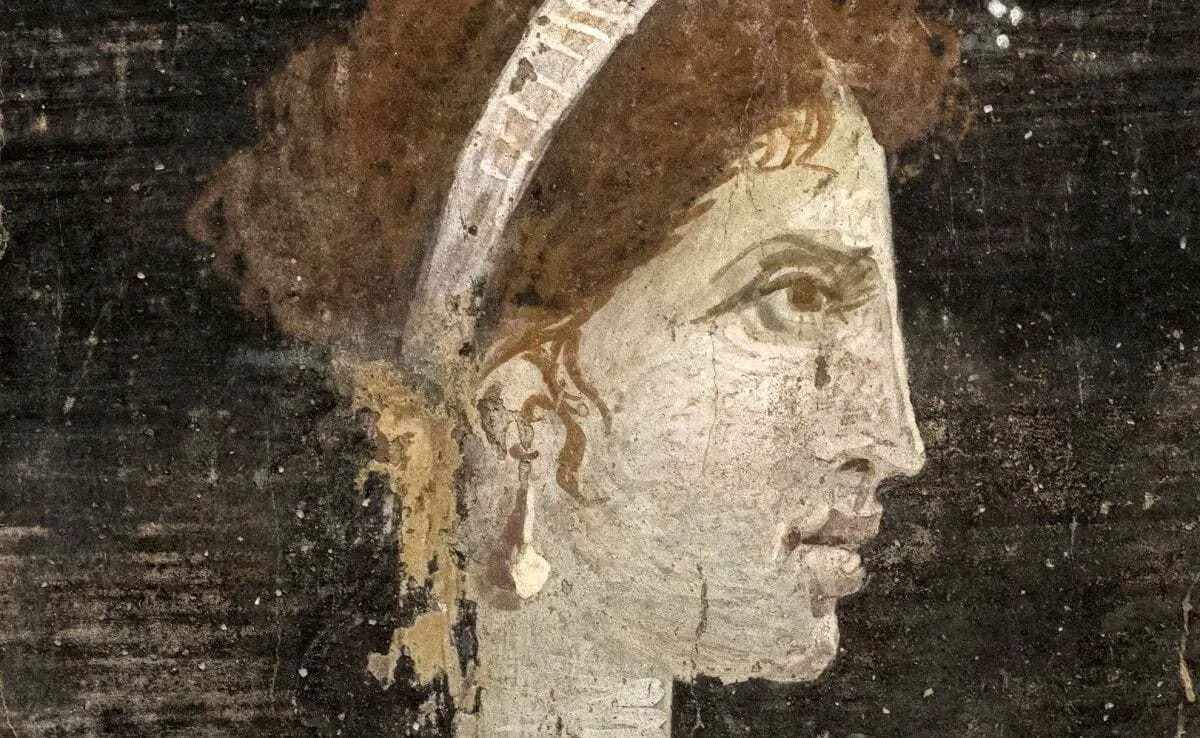

There remain no busts that can be reliably attributed to Cleopatra, but we do have various images of her surviving on ancient coinage. In these images, she is depicted as anywhere from average-looking to hook-nosed and manly. However, it must be remembered that coins in the ancient world were a powerful piece of political propaganda. The deliberate portrayal of Cleopatra with masculine features not dissimilar to her ancestral male rulers the Ptolemies was not an attempt to capture a true likeness, but rather to help legitimise the rule of a young female queen.

It is also important to keep in mind that ancient ideals of beauty were quite different to those of the modern Western world. For example, ancient Greek depictions of the beautiful love goddess Aphrodite invariably show a full-bodied woman with a prominent nose; a woman who modern society would probably advise to lose weight and get a nose job! Asking whether Cleopatra was beautiful is perhaps then a fruitless question, if beauty is truly in the eyes of the culture in which it is beheld.

Or maybe all we need do is move beyond beauty as a purely physical concept. Dio also tells us that Cleopatra had ‘a most delicious voice and a knowledge of how to make herself agreeable to everyone.” Likewise, Plutarch states that conversation with Cleopatra “had an irresistible charm, and her presence, combined with the persuasiveness of her discourse and the character which was somehow diffused about her behaviour towards others, had something stimulating about it.” He wrote that “there was sweetness also in the tones of her voice; and her tongue, like an instrument of many strings, she could readily turn to whatever language she pleased.”

The message is clear: Cleopatra’s allure had little to do with her physical appearance and a lot to do with her intellect, character and, apparently, the tone of her voice. When you consider how deeply involved both Caesar and Antony became with her, it is obvious that there must have been something more at play than just a sexy young body. After all, both were notorious womanisers and would surely not have fallen for Cleopatra on the basis of sex alone.

It seems likely that Cleopatra’s physical appearance was not more or less attractive than the next woman, yet through her wit, charm and daring she captivated not only two of the most powerful men of the ancient world, but the collective imagination of the entire world for all centuries that followed. That the most renowned beauty in human history was beautiful in character more so than in appearance could be an important lesson for our modern fixation on the purely physical.

References:

Bradford, E. 1971. Cleopatra, Corgi Books.

Cassius Dio. c. 200 CE. Book XLII, Roman History, trans. H.B. Foster, 1905.

Flamarion, E. 1997. Cleopatra: From History to Legend, Thames & Hudson.

Fletcher, J. 2008. Cleopatra the Great: The Woman Behind The Legend, Hodder & Stoughton.

Goldsworthy, A. 2010. Antony and Cleopatra, Orion Publishing Group.

Plutarch. c. 100 CE. Life of Antony, Parallel Lives, Loeb Classical Library, 1920.

Written by Robyn Antanovskii