An archaeological dig in the southeast of Turkey has unveiled a considerable number of clay tokens that were used as records of trade until the advent of writing, or so it was believed.

But the new cohort of tokens dates from a time when writing was common-thousands of years after the technology had been considered obsolete. Researchers compare it to the continued use of pens in the technological age of the word processor.

The tokens-small clay pieces in a variety of simple shapes- are thought to have been used as a simple bookkeeping system in prehistoric times.

One possible theory is that different types of tokens represented units of various commodities such as livestock and grain. These would be exchanged and later sealed in more clay as a permanent record of the trade- the world’s first contract.

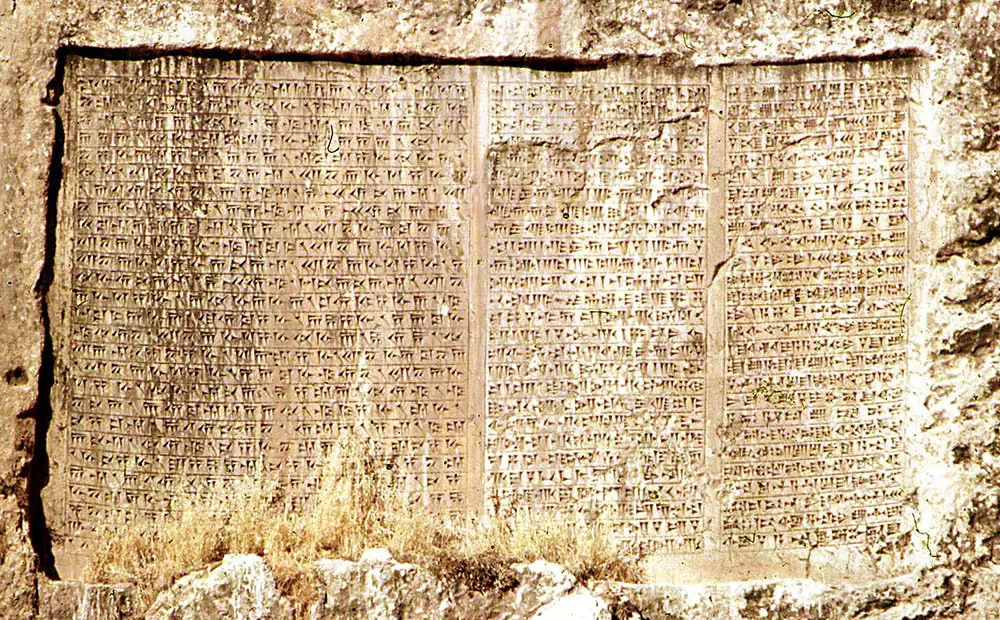

This system was used in the time leading to approximately 3000 BC, at which point clay tablets filled with pictorial symbols drawn using triangular-tipped reeds beginning to emerge: the creation of writing and thus, history.

From this time in the archaeological record, the tokens begin to shrink in number and they ultimately disappeared; leading to the assumption that writing quickly took over from the token system.

However, recent excavations at Ziyaret Tepe- the site of ancient city Tushan, a provincial capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire- have unearthed a substantial amount of tokens dating back to the first millennium BC: two thousand years after ‘cuneiform’- the very first form of writing- emerged on clay tablets.

“Complex writing didn’t stop the use of the abacus, just as the digital age hasn’t wiped out pencils and pens,” said Dr John MacGinnis from Cambridge’s MacDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, who led the research.

“In fact, in a literate society there are multiple channels of recording information that can be complementary to each other. In this case both prehistoric clay tokens and cuneiform writing used together.”

Archaeologists found the tokens in the main administrative building in Tushan’s lower town, accompanied by many cuneiform clay tablets as well as weights and clay sealings. An excess of 300 tokens were discovered in two rooms near the back of the building that MacGinnis describes as having the character of a ‘delivery area’, suggesting that is was once an ancient loading bay.

“We think one of two things happened here. You either have information about livestock coming through here, or flocks of animals themselves. Each farmer or herder would have a bag with tokens to represent their flock,” said MacGinnis.

“The information is travelling through these rooms in token form, and ending up inscribed onto cuneiform tablets further down the line.”

Archaeologists have said that, while cuneiform writing was more advanced, the combination of it with the flexibility of tokens the ancient Assyrians created a record-keeping system that was of a higher level of sophistication.

“The tokens provided a system of moveable numbers that allowed for stock to be moved and accounts to be modified and updated without committing to writing; a system that doesn’t require everyone involved to be literate.”

MacGinnis believes that the new evidence indicates that prehistoric tokens used in combination with cuneiform, as an empire-wide ‘admin’ system stretching across what is now Turkey, Syria and Iraq. At the time, roughly 900 to 600 BC, the Assyrian empire was the largest in the world.

The various tokens ranged from basic spheres, discs and triangles to tokens resembling animals, such as oxhide and bull heads.

While the majority of the cuneiform tablets discovered relate to grain trades, it is still unknown what the various tokens represent. The research team say that some of the tokens likely stand for grains, as well as different forms of livestock (such as goat and cattle), but- as they were used in the height of a large empire- it is a possibility that the tokens were used to represent goods such as oil, wool and wine.

“One of my dreams is that one day we’ll dig up the tablet of an accountant who was making a meticulous inventory of goods and systems, and we will be able to crack the token system’s codes,” said MacGinnis.

“The inventions of recording systems are milestones in the human journey, and any finds which contribute to the understanding of how they came about makes a basic contribution to mapping the progress of mankind,” he said.

Contributing Source: University of Cambridge

Header Image Source: WikiPedia