European researchers have recovered a genome of the bacterium Brucella melitensis from a 700-year-old-skeleton discovered in the ruins of a Medieval Italian village.

Reporting this week in mBio®, the online open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology, the authors used a technique called shotgun metagenomics to sequence DNA from a calcified nodule in the pelvic region of a middle-aged male skeleton excavated from the settlement of Geridu in Sardinia. It is thought that Geridu was abandoned in the late 14th century. Shotgun metagenomics has the ability to allow scientists to sequence DNA without looking for a specific target.

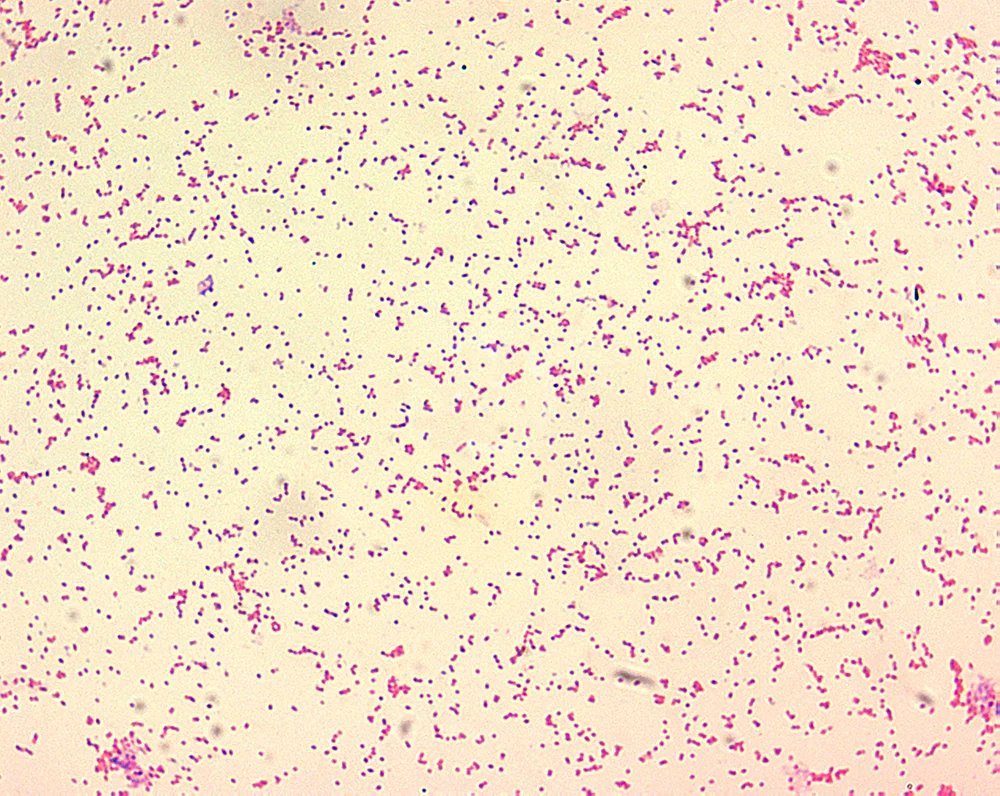

From this particular sample, the team of researchers recovered the genome of Brucella melitensis, which causes the infection brucellosis in livestock and humans. In humans, brucellosis is typically acquired through the ingestion of unpasteurized dairy products or direct contact with infected animals. Symptoms of the infection include fevers, arthritis and swelling of the heart and liver. The disease can still be found in the Mediterranean region.

“Normally when you think of calcified material in human or animal remains you think about tuberculosis, because that’s the most common infection that leads to calcification,” says senior study author Mark Pallen, PhD, professor of microbial genomics at Warwick Medical School in Coventry, England. “We were a bit surprised to get Brucella instead.”

Following further experimentation, the research team unveiled that the DNA fragments extracted had the appearance of aged DNA-they were shorter than contemporary strands and characteristic mutations at the ends. The researchers also discovered that the medieval Brucella strain, which they called Geridu-1, was closely related to a recent Brucella strain called Etheer, which was identified in Italy in 1961, along with two other Italian strains identified in 2006 and 2007.

Pallen and others have used shotgun metagenomics previously in order to detect pathogens in contemporary and historical human material. Last summer, Pallen published a report in the New England Journal of Medicine describing the recovery of tuberculosis genomes from the lung tissue of a 215-year-old mummy from Hungary. Pallen also managed to identify Eschericia coli from stool samples during a 2011 outbreak in Germany.

Pallen’s team is currently testing the technique on a range of additional samples from different time periods and locations. These include historical material from Hungarian mummies, Egyptian mummies, a Korean mummy from the 16th or 17th century, contemporary samples from the Gambia in Africa and lung tissue from a French queen from the Merovingian dynasty, which ruled France from the 5th to the 8th centuries.

“Metagenomics stands ready to document past and present infections, shedding light on the emergence, evolution and spread of microbial pathogens,” Pallen says. “We’re cranking through all of these samples and we’re hopeful that we’re going to find new things.”

Contributing Source: American Society for Microbiology

Header Image Source: Wikimedia