Poor peepers are a problem, even if you are a big, bad sea scorpion.

One minute, you are one of the most feared predators, scouring the waters for your next meal. The next, thanks to a post-extinction eye exam by Yale University scientists, you are reduced to trolling for the much weaker, soft-bodied animals that you happen to stumble upon at night.

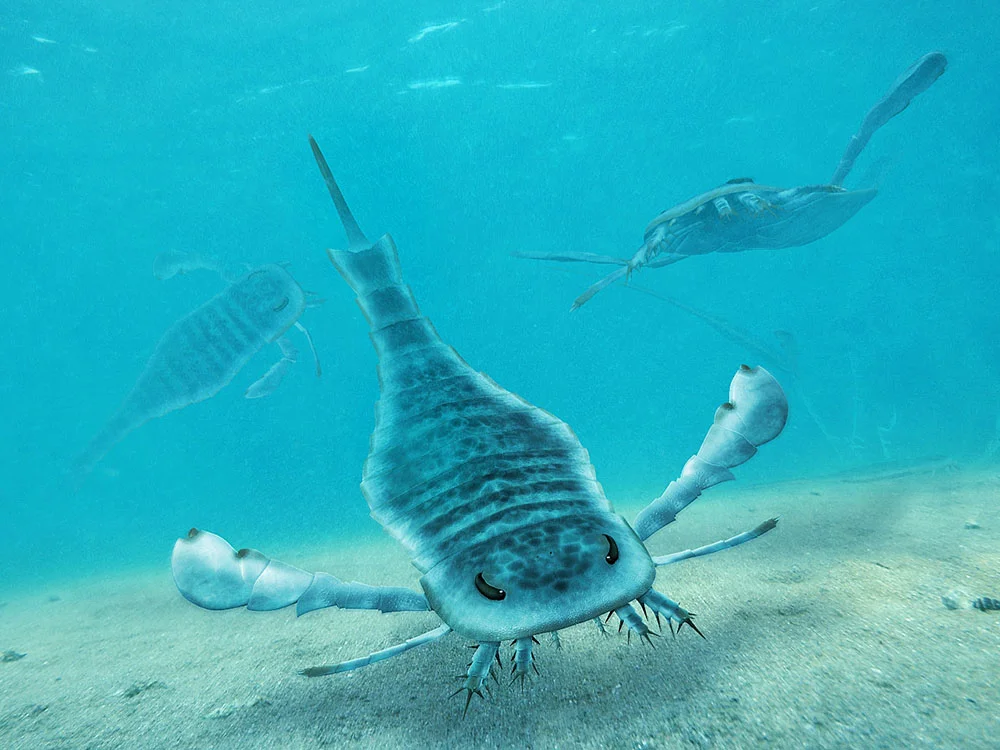

This is the case for the giant pterygotid eurypterid, the largest arthropod to ever grace the earth. A new paper by Yale paleontologists, published in the journal Biology Letters, dramatically reinterprets the sea creature’s habits, capabilities and ecological role. The paper is entitled “What big eyes you have: The ecological role of giant pterygotid euryterids.

“We thought it was this large, swimming predator that dominated Paleozoic seas,” said Ross Anderson, a Yale graduate student and lead author of the paper. “But one thing it would need is to be able to find the prey, to see it.”

Pterygotids, which could reach sizes of over two meters long, roamed shallow, shoreline basins for 35 million years. Due to the creature’s size, long-toothed grasping claws in the front of their mouth, and their forward facing, compound eyes, scientists have been under the impression that these sea scorpions were fearsome predators.

Research conducted by Richard Laub of the Buffalo Museum of Science cast doubt on the ability of pterygotid’s claws to penetrate armored prey. Yale’s eye study further confirmed the idea that pterygotids were not the top predators they were previously thought to be.

“Our analysis shows that they could not see as well as other eurypterids and may have lived in dark or cloudy water. If their claws could not penetrate the armor of contemporary fish, the shells of cephalopods, or possibly even the cuticle of other eurypterids, they may have preyed on soft-bodied, slower-moving prey,” said Derek Briggs, the G. Evelyn Hutchinson Professor of Geology & Geophysics at Yale and curator of invertebrate paleontology at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. Briggs co-authored the paper.

Victoria McCoy, a Yale graduate student, developed an innovative mathematical analysis method to obtain a better understanding of properties of the sea scorpion’s eyes. Yale also used imaging technology with backscattered electrons on a scanning electron microscope to reveal the eye lenses without causing damage to the fossils. The results were compared with the eyes of other extinct species during the same time period, as well as modern day species such as the horseshoe crab.

Although the data could not be used to determine the nearsightedness or farsightedness of the animal, it did unveil a basic visual acuity level for the sea scorpions, which had thousands of eye lenses. “We measured the angle between the lenses of the eye itself,” Anderson said. “The smaller the angle, the better the eyesight.”

Unfortunately for the prehistoric sea giant, their eyesight was proved to be less than exceptional. In fact, it was found that their vision grew worse as they grew larger. It certainly wasn’t on par with high-level arthropod predators such as mantis shrimp and dragonflies, said the scientists.

“Maybe this thing was not a big predator, after all,” Anderson said. “It’s possible it was more of a scavenger that hunted at night. It forces us to think about these ecosystems in a very different way.”

The Yale team’s vision testing methodology may prove fundamental in the understanding of how other species functioned as well. You could use it on a number of different organisms,” according to Anderson. “It will be particularly useful with other arthropod eyesight examinations.”

Former Yale postdoctoral fellow Maria McNamara of University College Cork also co-authored the paper. The research began as a project in a fossil preservation class taught by Briggs at Yale University.

Contributing Source: Yale University

Header Image Source: WikiPedia