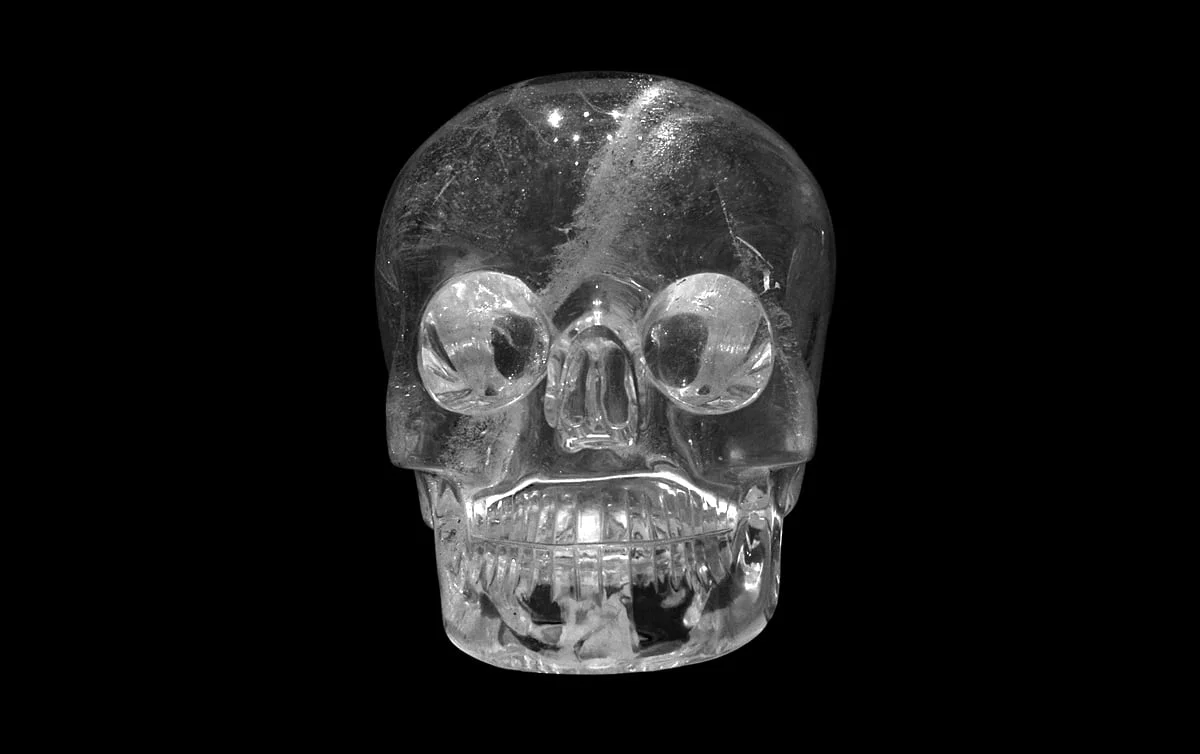

The crystal skulls have been the subject of much controversy and speculation, claimed to be the work of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures, such as the Aztec and Maya.

There are a dozen or so crystal skulls in private and public museum collections, mostly made from clear or milky white quartz, a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide).

Pseudo theories about the skulls claim that they have paranormal powers, enabling the gift of premonitions, cure diseases, or forestalling a catastrophe allegedly predicted or implied by the ending of the Maya calendar b’ak’tun-cycle.

In Mesoamerican artwork, skulls are featured prominently in a variety of settings, such as Aztec monoliths made from volcanic rock, or the skull masks of obsidian, cabochon and jade. Both the Aztec and Maya also displayed human skulls on a rack known as a tzompantli, encapsulating the practice into stone at sites such as Chichén Itzá, where a large carved tzompantli displays over 500 bas-relief skulls.

During the 19th century, public and scholarly interest in Mesoamerican sites led to an increase in the trade of fake pre-Columbian artefacts. The trade became so problematic, that Smithsonian archaeologist, William Henry Holmes, wrote an article called “The Trade in Spurious Mexican Antiquities” for Science in 1886.

In 1857, Eugène Boban, a French antiquarian, art dealer, and “official archaeologist” of the court of Maximilian I of Mexico, headed an expedition commissioned by Napoleon III to collect Mexican art and artifacts. He exhibited his finds at the Trocadéro, where he is reported to have displayed a collection of crystal skulls.

After opening a shop in New York, Boban sold a crystal skull to American entrepreneur, George H. Sisson, then passing to George F. Kunz and displayed at the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The skull was auctioned off by Tiffany and Co to the British Museum in 1898, where it was placed on display as an Aztec artefact. Boban sold another crystal skull to French ethnologist and collector, Alphonse Pinart, who donated the skull to the Trocadéro Museum, now displayed at the Musée du Quai Branly.

A scientific study on the skulls revealed that the indented lines marking the teeth were carved using relatively modern rotary tools. A closer examination of the composition showed that they have chlorite inclusions only found in Madagascar and Brazil, and thus unobtainable or unknown within pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. The study also suggests that the skulls were crafted in Germany during the 19th century, possibly in the workshops of Idar-Oberstein which was renowned for crafting quartz objects.

In 1900, Boban gave a lecture in Paris at the Americanist Conference on Ethnographic Sciences, where he stated: “numbers of so-called rock crystal pre-Columbian skulls have been so adroitly made as almost to defy detection and have been palmed off as genuine”.

In 1924, Anna Mitchell-Heges (the adopted daughter of adventurer Frederick Albert Mitchell-Hedges), claimed to discover another crystal skull inside a temple in Lubaantun, Belize. It has been determined that Frederick Albert Mitchell-Hedges purchased the skull at Sotheby’s auction house in 1943, and a scientific study in 2007 has shown that the skull was carved with a rotary tool coated with a hard abrasive.

The study concluded that the skull was probably carved in the 1930s, with Smithsonian researchers stating that the skull was “very nearly a replica of the British Museum skull – almost exactly the same shape, but with more detailed modelling of the eyes and the teeth.”

More recently, a crystal skull was mailed to the Smithsonian Institution anonymously, claiming to be of Aztec origin from the collection of Porfirio Díaz, a Mexican general and politician who served seven terms as President of Mexico during the 19th century. It has been determined that the skull was carved using Silicon carbide (SiC), also known as carborundum, an abrasive mass-produced from 1893.

The skulls examined were manufactured in the mid-19th century or later, almost certainly in Europe, during a time when interest in ancient culture abounded. The skulls have no written accounts in the any ancient codex, or mythology and folklore associated with Mesoamerican or other Native American stories, concluding that the crystal skulls are nothing more than a 19th century invention that has morphed into a fake narrative of the Aztec and Maya civilisations.

Header Image – British Museum Crystal Skull – Image Credit : Vassil – CC0 1.0