The Samnites were an Italic civilisation who lived in Samnium, a region of Southern Italy that includes the present-day Abruzzo, Molise and Campania.

They were an Oscan-speaking people, an extinct Indo-European language of southern Italy spoken by several tribes that includes the Aurunci and the Sidicini. The longest and most important inscription of the Samnite dialect is the small bronze Tabula Agnonensis, which is engraved in full Oscan alphabet.

Scholars such as Strabo suggest that the Samnites were an offshoot of the Sabines from the central Apennine Mountains, whilst another origin myth connects them with the Spartans. The latter likely comes from Ancient Greek legends to form a connection with the Italic peoples for alliances, although archaeological evidence suggests that the Samnites developed from a pre-existing Italian culture.

Most of their territory consisted of rugged and mountainous terrain, with a mixed economy focused on highly developed forms of subsistence agriculture, mixed farming, animal husbandry, sheep farming, pastoralism, and smallholdings.

From the Iron Age, the territory was ruled by chieftains and an elite group, but by the 3rd and 4th century BC the Samnite political system developed into a hierarchy focused on rural settlements led by magistrates.

At the bottom of the hierarchy were the vici grouped into cantons called Pagi, organised into the tribal groups called the touto. Each touto was led by an elected official known as a meddis, who governed through a system known as the meddíss túvtiks.

This developed into the Kombennio, an early form of an assembly or Senate that was responsible for enforcing laws and electing officials, although society was still dominated by an elite group of families such as the Papii, Statii, Egnatii, and Staii.

Samnite religion worshipped both spirits called numina and gods and goddesses. The Samnites honoured their gods by sacrificing live animals and using votive offerings. Few Samnite gods and goddesses are known, although there’s evidence that they worshiped Vulcan, Diana, Mars and Mefitis (goddess of the foul-smelling gases of the earth).

Strabo states that the Samnites would take ten virgin women and ten young men, who were considered to be the best representation of their sex and mate them. Following this, the best women would be given to the best male, then the second-best women to the second-best male until all were coupled.

Samnite soldiers were generally armed with projectiles such as spears and javelins, whilst swords were highly valued in Samnite society, often depicted on pottery, figurines, and Samnite art that shows soldiers receiving swords in ritual ceremonies.

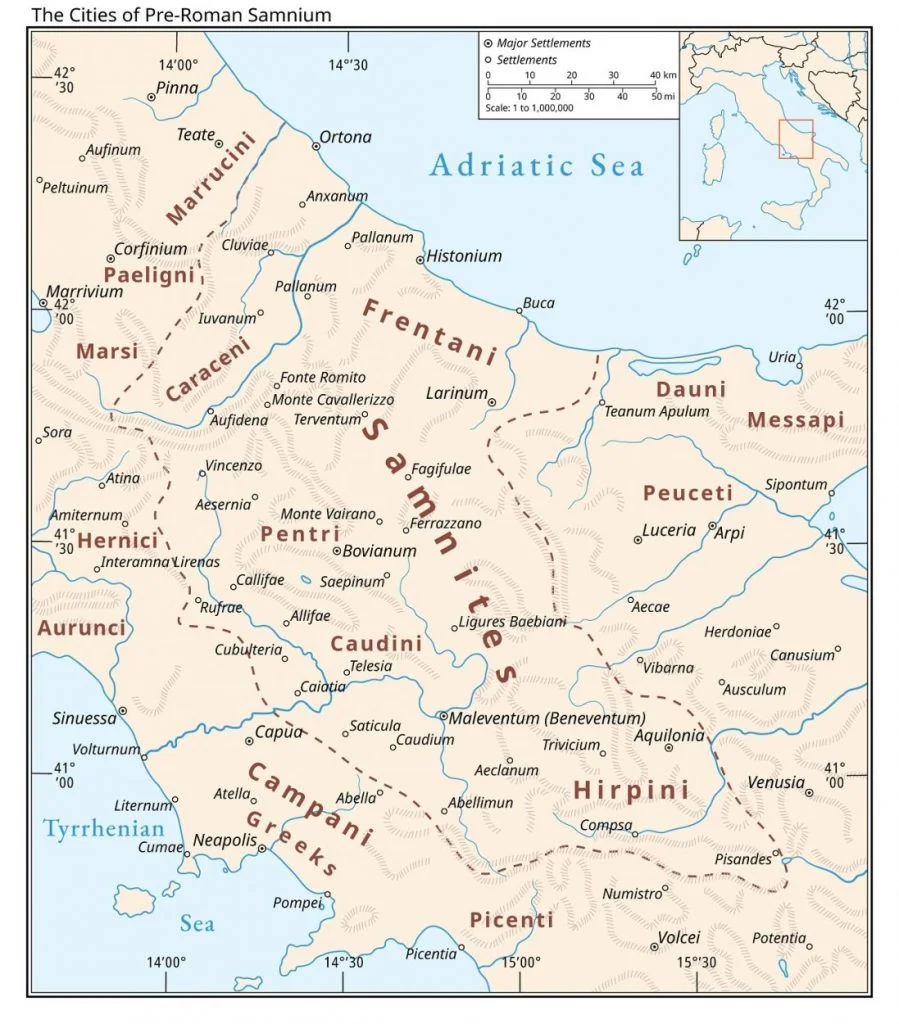

The Samnites and Romans first came into contact after the Roman conquest of the Volscians during the 4th century BC. Four cantons, consisting of the tribal Hirpini, Caudini, Caraceni, and Pentri formed a Samnite confederation similar to the Latin League, coming into conflict with the Romans as a result of Rome’s intervention to rescue the Campanian city of Capua from a Samnite attack.

This led to the Samnite Wars, a period of three major wars over half a century, resulting in a Samnite defeat at the Battle of Aquilonia and the assimilation of all Samnite territories and peoples into the Roman Republic.

Roman historians nicknamed the Samnite military the Belliger Samnis, loosely translated as the “Warrior Samnites”, whilst the Roman historian, Titus Livius (59 BC – AD 17), described an elite group of Samnite soldiers known as the legio linteata, meaning “linen legion”, that used flamboyant equipment and took an oath to never flee from battle.

Such accounts are likely a romanticised portrayal, however, Livy does describe the Samnite military forming closed formations as tightly knit phalanxes and comprising of cohorts divided into maniples which the Romans later adopted for their own army.

The legacy of the Samnites can be found in the archaeological record, where coins, pottery, architectural remains and Samnite art has been excavated in former Samnite centres such as Saepinum and Caiatia.

Header Image Credit : Public Domain