The Black Death, also known as the Pestilence, was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Afro-Eurasia during the 14th century.

The disease is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and spread mainly by fleas, leading to the death of 75–200 million people.

In 1347, the plague first entered the Mediterranean via trade ships transporting goods from the territories of the Golden Horde in the Black Sea. This first wave further extended into a 500-year-long pandemic, the so-called Second Plague Pandemic, which lasted until the early 19th century.

The origins of the Second Plague Pandemic have long been debated. One of the most popular theories has supported its source in East Asia, specifically in China. To the contrary, the only so-far available archaeological findings come from Central Asia, close to Lake Issyk Kul, in what is now Kyrgyzstan.

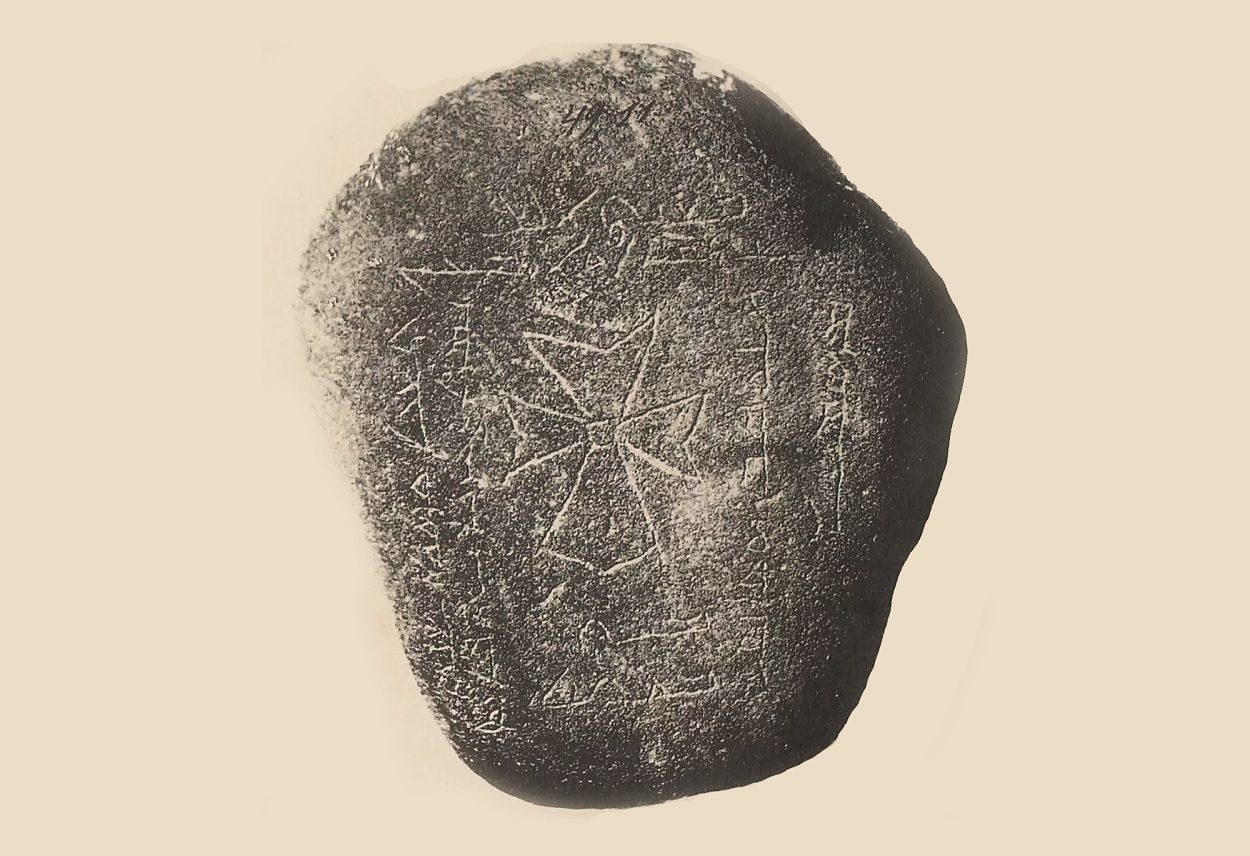

These findings show that an epidemic devastated a local trading community in the years 1338 and 1339. Specifically, excavations that took place almost 140 years ago revealed tombstones indicating that individuals died in those years of an unknown epidemic or “pestilence”. Since their first discovery, the tombstones inscribed in Syriac language, have been a cornerstone of controversy among scholars regarding their relevance to the Black Death of Europe.

In this study, an international team of researchers analysed ancient DNA from human remains as well as historical and archaeological data from two sites that were found to contain “pestilence” inscriptions.

The team’s first results were very encouraging, as DNA from the plague bacterium, Yersinia pestis, was identified in individuals with the year 1338 inscribed on their tombstones. “We could finally show that the epidemic mentioned on the tombstones was indeed caused by plague”, says Phil Slavin, one of the senior authors of the study and historian at the University of Sterling, UK.

The Black Death source strain

Researchers have previously associated the Black Death’s initiation with a massive diversification of plague strains, a so-called Big Bang event of plague diversity. But the exact date of this event could not be precisely estimated, and was thought to have happened sometime between the 10th and 14th centuries.

The team now pieced together complete ancient plague genomes from the sites in Kyrgyzstan and investigated how they might relate with this Big Bang event. “We found that the ancient strains from Kyrgyzstan are positioned exactly at the node of this massive diversification event. In other words, we found the Black Death’s source strain and we even know its exact date [meaning the year 1338]”, says Maria Spyrou, lead author and researcher at the University of Tübingen.

But where did this strain come from? Did it evolve locally or did it spread in this region from elsewhere? Plague is not a disease of humans; the bacterium survives within wild rodent populations across the world, in so-called plague reservoirs. Hence, the ancient Central Asian strain that caused the 1338-1339 epidemic around Lake Issyk Kul must have come from one such reservoir. “We found that modern strains most closely related to the ancient strain are today found in plague reservoirs around the Tian Shan mountains, so very close to where the ancient strain was found. This points to an origin of Black Death’s ancestor in Central Asia”, explains Johannes Krause, senior author of the study and director at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

The study demonstrates how investigations of well-defined archaeological contexts, and close collaborations among historians, archaeologists and geneticists can resolve big mysteries of our past, such as the infamous Black Death’s origins, with unprecedented precision.

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04800-3

Header Image – Plague inscription from the Chu-Valley region in Kyrgyzstan. The inscription is translated as follows: “In the Year 1649 [= 1338 CE], and it was the Year of the tiger, in Turkic [language] “Bars”. This is the tomb of the believer Sanmaq. [He] died of pestilence” – Image Credit : A.S. Leybin, August 1886