DNA analysis has revealed the presence of ‘Yersinia Pestis’ – the pathogen that causes plague – in skeletal remains from individual burials in medieval Cambridgeshire, confirming for the first time that not all plague victims were buried in mass graves.

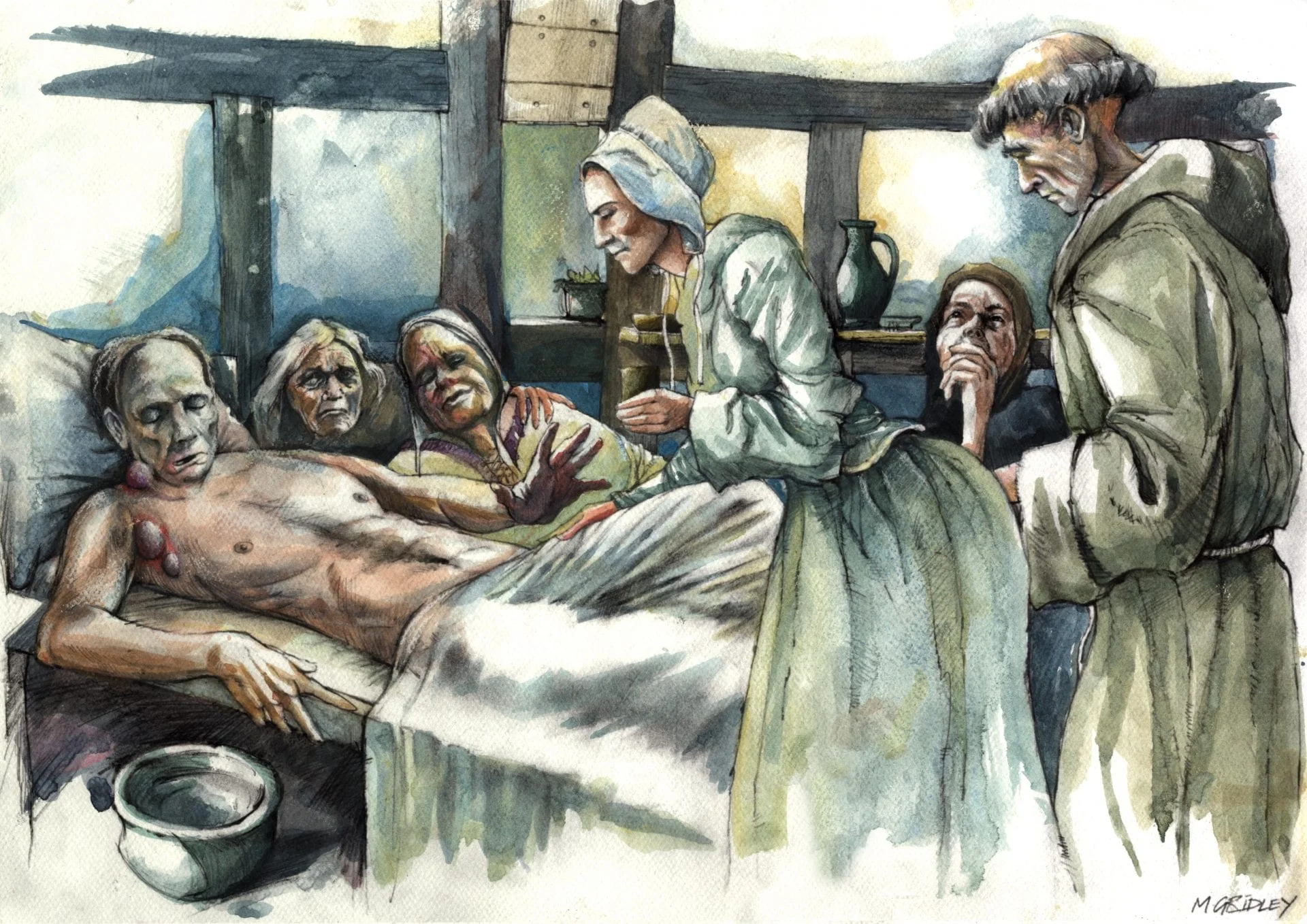

Compassion and care were shown to victims even during traumatic times during past pandemics.

In the mid-14th century Europe was devastated by a major pandemic – the Black Death – which killed between 40 and 60 per cent of the population. Later waves of plague then continued to strike regularly over several centuries.

Plague kills so rapidly it leaves no visible traces on the skeleton, so archaeologists have previously been unable to identify individuals who died of plague unless they were buried in mass graves.

Whilst it has long been suspected that most plague victims received individual burial, this has been impossible to confirm until now.

By studying DNA from the teeth of individuals who died at this time, researchers from the After the Plague project, based at the Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, have identified the presence of Yersinia Pestis, the pathogen that causes plague.

These include people who received normal individual burials at a parish cemetery and friary in Cambridge and in the nearby village of Clopton.

Lead author Craig Cessford of the University of Cambridge said, “These individual burials show that even during plague outbreaks individual people were being buried with considerable care and attention. This is shown particularly at the friary where at least three such individuals were buried within the chapter house. Cambridge Archaeological Unit conducted excavations on this site on behalf of the University in 2017.

The individual at the parish of All Saints by the Castle in Cambridge was also carefully buried; this contrasts with the apocalyptic language used to describe the abandonment of this church in 1365 when it was reported that the church was partly ruinous and ‘the bones of dead bodies are exposed to beasts’.”

The study also shows that some plague victims in Cambridge did, indeed, receive mass burials.

Yersinia Pestis was identified in several parishioners from St Bene’t’s, who were buried together in a large trench in the churchyard excavated by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit on behalf of Corpus Christi College.

This part of the churchyard was soon afterwards transferred to Corpus Christi College, which was founded by the St Bene’t’s parish guild to commemorate the dead including the victims of the Black Death. For centuries, the members of the College would walk over the mass burial every day on the way to the parish church.

Cessford concluded, “Our work demonstrates that it is now possible to identify individuals who died from plague and received individual burials. This greatly improves our understanding of the plague and shows that even in incredibly traumatic times during past pandemics people tried very hard to bury the deceased with as much care as possible.”

Header Image : Reconstruction of plague victim from All Saints, Cambridge. Image Credit: Mark Gridley