The lifestyle and eating habits of human groups that have lived for thousands of years can be examined by tooth.

An international research group analyzed the prehistoric findings of the Neolithic Age. In addition to providing knowledge about the lifestyles of people who lived in prehistoric times, a novel study of tooth remains paved the way for other methods previously not used. This study applies the complementary approaches of stable isotope and dental microwear analyses to study the diets of past people living in today’s Hungary. Their joint results were published in the scientific journal Scientific Reports.

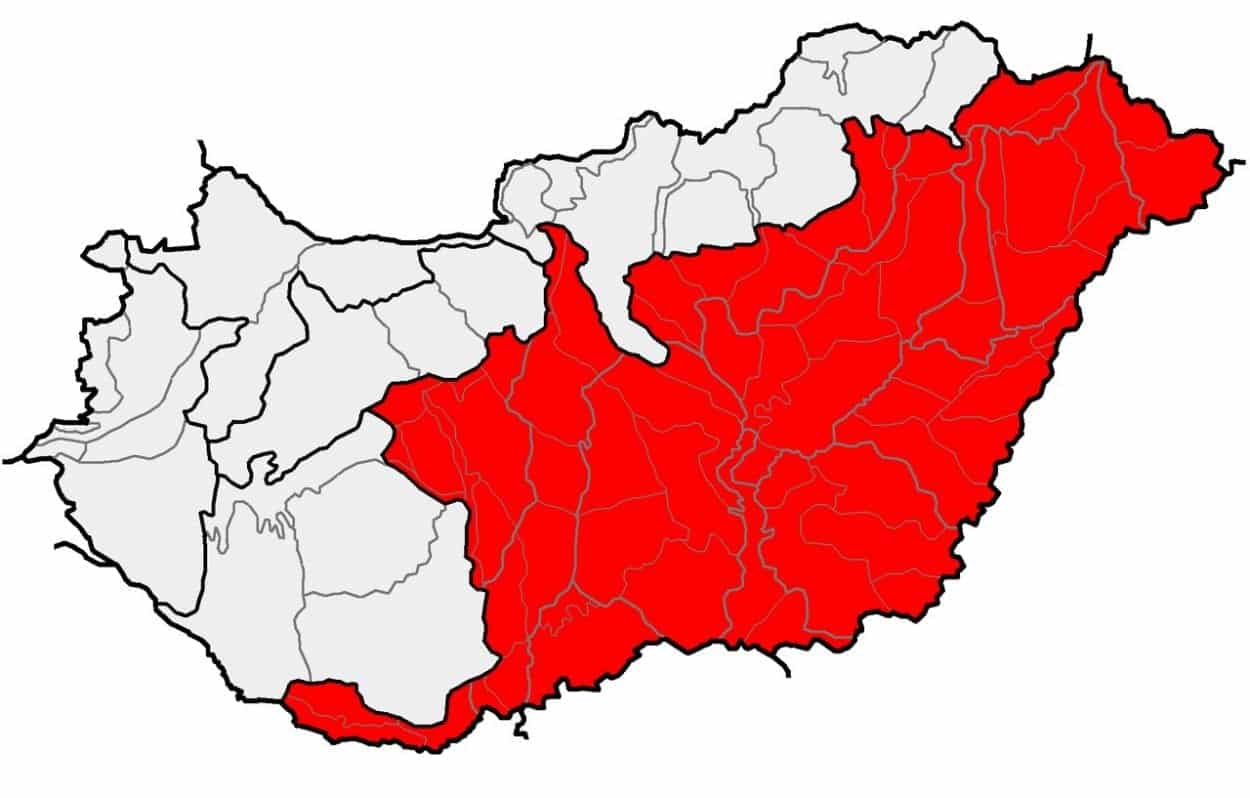

The Great Hungarian Plain is considered one of the most interesting areas for archeology because of its central geographic position in the European continent. The area played a key role in the spread and development of farming across Europe and was the meeting point for eastern and western European cultures. As such, it was a major cultural and technological transitional region throughout prehistory. But despite being a rich archeological region, few studies have analyzed the diets of the past people living in today’s Hungary. In this context, researchers from the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES-CERCA) and the Universitat Rovira i Virgili (URV) in Tarragona (Spain), have carried out interdisciplinary research contributing new data about the evolution of the diets of the first agricultural and pastoral communities in Central Europe. This investigation has just been published in the journal Scientific Reports.

The study is focused on Great Hungarian Plain populations that lived from Middle Neolithic (5,500 – 5,000 BC) to Late Bronze Age (1,450 – 800 BC). Important changes in human diets occurred during this timeframe, influenced, most probably, by the socioeconomic, demographical and cultural transformations characterizing this period of some 5,000 years.

Raquel Hernando is a co-author of the paper carrying out her PhD studies with the URV and IPHES-CERCA and is beneficiary of a Marti-Franqueses Research Grant (URV2019PMF-PIPF-59). She says: “The demographic increase during the transition from Neolithic to Copper Age, produced changes in the settlement pattern and an increased focus on animal husbandry with a more reliance on cattle”. And she adds “With the arrival of bronze metallurgy from the eastern steppe, significant changes occurred in the intensification of agriculture, with more hierarchical societies and fortified settlements”.

All of these events took place at the same time over much of the European continent and “…had implications on the dietary subsistence patterns of the human populations of that time” points out Beatriz Gamarra, a postdoctoral Beatriu de Pinós AGAUR Fellow and co-author of the paper in collaboration with other academics of research centres and universities from Ireland, Hungary and Portugal.

The team studied the diets of past human populations living in the Great Hungarian Plain from the Middle Neolithic and Late Bronze Age periods, demonstrating that, compared with subsequent periods, people consumed less abrasive and/or more processed foods during Middle Neolithic period. The Middle Neolithic people consumed meat and cereals (like wheat, einkorn and barley), although their diets varied between the sites. The researchers also found that, although other crops were consumed increasingly during the Middle Bronze Age (such as millet), this did not have any effects on the abrasiveness of the food and the way they processed it.

These results have been obtained from the same individuals using two approaches that were found to be complementary: stable isotope and dental microwear analyses. Each method is indicative of different dietary traits and few studies have combined both of them to infer ancestral diets. In this sense, Raquel Hernando states:

“The novelty of our study is that, thanks to the rich Hungarian archaeological human record, we have been able to employ both approaches on the same individuals, something that it has rarely been applied in previous studies, and has been developed in this exhaustive work”.

Dental microwear analysis applied on molars provides information about the abrasiveness of the diets and the previous process of the foods consumed. Meanwhile, the stable isotopes study provides information about the origins of the animal proteins present in the ingested foods. Beatriz Gamarra highlights:

“We have demonstrated the complementary of these two techniques, which is not very common on this kind of research, as many of the archaeological context of the samples employed (such as collective burials) do not allow for this kind of combination on the same individuals’ skeletal remains.”

To carry out this research, a total of 89 individuals sampled from 17 archaeological sites dating to different periods and situated in the north-eastern part of the Great Hungarian Plain were employed. The material is stored in the Herman Ottó Museum in Miskolc, Hungary. Raquel Hernando specifies:

“From each individual, we have employed their teeth (first and second molars) for the microwear study, postcranial remains for the stable isotope analysis, and the petrous bone (inner ear) to perform ancient DNA analyses in order to biologically sex them “, specifies Raquel Hernando.

Dental microwear consists of quantifying a series of marks, such as striations and pits, formed on tooth enamel surfaces during the chewing process due to the presence in the foods of particles harder than tooth enamel. Using information from the microwear patterns, the abrasiveness of the food ingested and/or the previous process the foods might suffered before its consumption, can be inferred. To avoid damaging the original remains, molds of the teeth were made during the research stay of Raquel Hernando at the University College Dublin (UCD, Ireland). These molds were later analysed at the Servei de Recursos Cienífics I Tècnics facilities of the URV (at Seslades Campus, Tarragona).

The stable isotope analyses are based on the principle that the biochemical composition of the food consumed by animals is preserved in their body tissues. The carbon and nitrogen isotopic fractions were calculated from bone collagen and are indicative of the origin of the proteins consumed by the individuals a few years prior to their death. This research was carried out by Beatriz Gamarra at the School of Archaeology of University College Dublin (Ireland) thanks to funding from her previous MSCA (Marie Sk?odowska-Curie Actions) project.

Header Image – The territory of the GHP in Hungary – Image Credit : Miaow Miaow – Public Domain