An international team, led by Dr Sabrina Simon (Wageningen University & Research) and Dr Hojun Song (Texas A&M), succeeded in tracing the evolution of acoustic communication in the insect family of crickets and grasshoppers (Orthoptera).

The results show that crickets were the first species to communicate, approximately 300 million years ago. The results are also significant because it was the first time this analysis has been done on such a large scale. The publication by Dr Simon et al. appeared in the prominent scientific journal Nature Communications today.

‘Insects have a vital role in terrestrial ecosystems. To understand how insects influence, sustain or endanger ecosystems, and what happens when they decline or even disappear, we first need to understand why insects are so species-rich and how they evolved’, says Dr Simon.

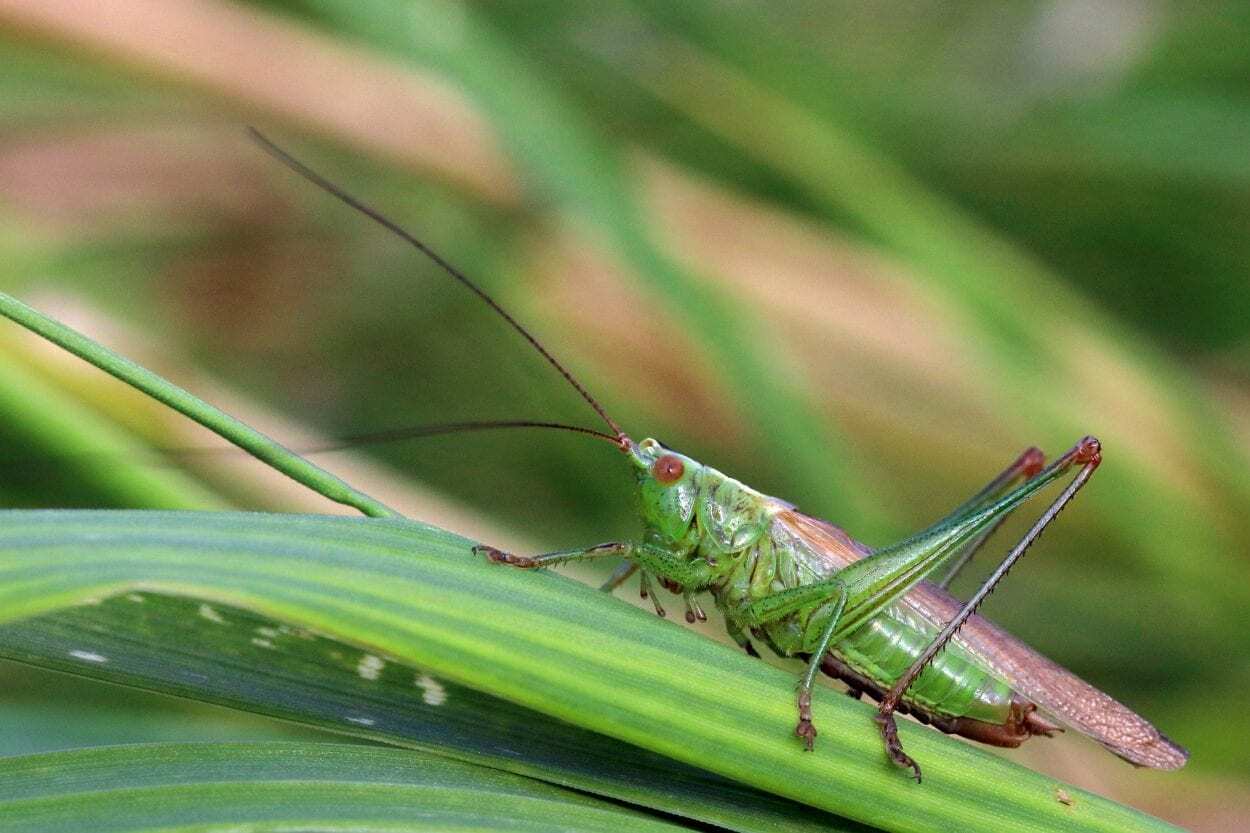

Orthoptera is a charismatic insect group of high evolutionary, ecological and economic importance such as crickets, katydids, and grasshoppers. They are a prime example of animals using acoustic communication. Using a large genomic dataset, the team established a phylogenetic framework to analyse how hearing and sound production originated and diversified during several hundred million years of evolution.

Chirping

The familiar sound of crickets was first experienced 300 million years ago, the researchers found. It was experienced because specialised and dedicated hearing organs were developed later. Sound production originally served as a defence mechanism against enemies, who were startled by the vibrating cricket in their mouths. Later on, the ability to produce sound started to play a prominent role in reproduction, because sound-producing crickets had a greater chance of being located by a female.

Insects are one of the most species-rich groups of animals. They are crucial in almost every ecosystem. The number of insects is rapidly declining. Insect species are becoming invasive or disappearing due to climate change. That – in itself – has an impact on ecosystems and eventually on humans. ‘We need to understand the evolutionary history of this amazingly successful animal group. This is also important for our (daily) economic life because only then can we understand what happens when insect species decline or even disappear’, says Dr. Simon.

Wageningen University & Research

Header Image Credit : Public Domain