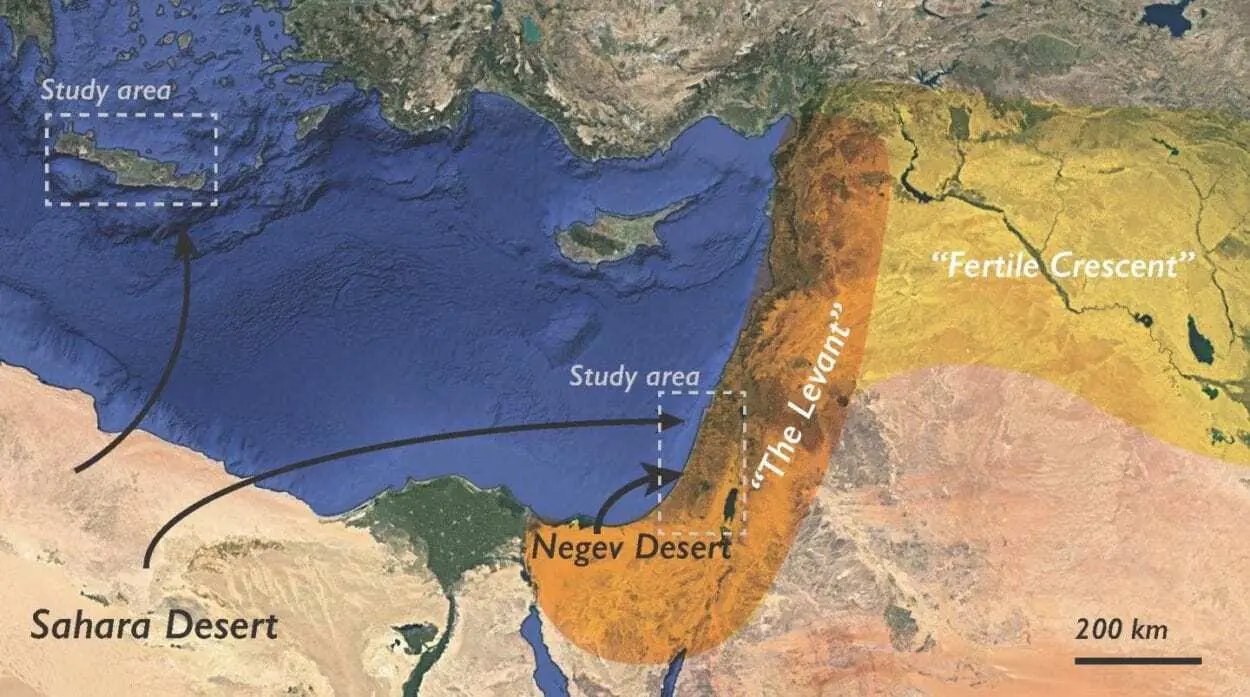

When early humans began to travel out of Africa and spread into Eurasia over a hundred thousand years ago, a fertile region around the eastern Mediterranean Sea called the Levant served as a critical gateway between northern Africa and Eurasia.

A new study, published in Geology, shows that the existence of that oasis depended almost entirely on something we almost never think about: dust.

Dr. Rivka Amit, at the Geological Survey of Israel, and her team initially set out with a simple question: why are some soils around the Mediterranean thin and why are some thick?

Their investigation led them to discover not only that dust deposition played a critical role in forming thick soils in the Levant, but also that had the source of dust not changed 200,000 years ago, early humans might have had a much tougher time leaving Africa, and parts of the Fertile Crescent wouldn’t have been so hospitable for civilization to take root.

Thick soils tend to form in areas with wet, humid climates, and thin soils form in arid environments with lower weathering rates. But in the Mediterranean, where much of the bedrock is dissolvable carbonate, the opposite is true: wetter northern regions have thin, unproductive soils, and more arid southeastern regions have thick, productive soils.

Some scientists have attributed these patterns to differences in the rates of erosion, driven by human activity. But for Amit, who has been studying the area for years, a high erosion rate alone didn’t make sense. She challenged the existing hypotheses, reasoning that another factor–dust input–likely plays a critical role when weathering rates are too slow to form soils from bedrock.

To assess the influence of dust on Mediterranean soils, Amit and her team needed to trace the dust back to its original source. They collected dust samples from soils in the region, as well as nearby and far-flung dust sources, and compared the samples’ grain size distribution. The team identified a key difference between areas with thin and thick soils: thin soils comprised only the finest grain sizes sourced from distant deserts like the Sahara, whereas the thicker, more productive soils had coarser dust called loess, sourced from the nearby Negev desert and its massive dune fields.

The thick soils in the eastern Mediterranean formed 200,000 years ago when glaciers covered large swaths of land, grinding up bedrock and creating an abundance of fine-grained sediments. “The whole planet was a lot dustier,” Amit said, which allowed extensive dune fields like those in the Negev to build up, creating new sources of dust and ultimately, thicker soils in places like the Levant.

Amit, then, had her answer: regions with thin soils simply hadn’t received enough loess to form thick, agriculturally productive soils, whereas the southeastern Mediterranean had. “Erosion here is less important,” she said. “What’s important is whether you get an influx of coarse [dust] fractions. [Without that], you get thin, unproductive soils.”

Amit didn’t stop there. She now knew that the thickest soils had received a large flux of coarse dust, leading to the area’s designation as the “land of milk and honey” for its agricultural productivity. Her next question was, had it always been like this?

She was surprised at what they found. Looking below the loess in the soil profile, they found a dearth of fine-grained sediments. “What was [deposited] before the loess were very thin soils,” she said. “It was a big surprise… The landscape was totally different, so I’m not sure that people would [have chosen] this area to live in because it was a harsh environment and [an] almost bare landscape, without much soil.” Without the changing winds and formation of the Negev dune field, then, the fertile area that served as a passage for early humans may have been too difficult to pass through and survive.

In the modern Mediterranean, the soils aren’t accumulating any more. “The dust source is cut off,” Amit explained, since the glaciers retreated in the Holocene, “now we’re only reworking the old loess.” Even if there were a dust source, it would take tens of thousands of years to rebuild soil there. That leaves these mountainous soils in a fragile state, and people living there must balance conservation and agricultural use. Employing responsible agricultural practices in the region, as terracing has been used for thousands of years, is critical for soil preservation if agriculture is to continue.

Header Image Credit : Public Domain