In ancient Rome, you could tell a lot about a person from the look of their garden. Ancient gardens were spaces used for many activities, such as dining, intellectual practice, and religious rituals.

They also offered the opportunity to flaunt horticultural skills as well as travels. As such, gardens were taken rather seriously by Romans. Walking had an important role here, as there is no better way to show off your garden than to take people on walks through it.

The role of horticulture in the construction of elite identity in ancient Rome is one of the topics I am investigating, while the excavation of an ancient Pompeian garden I co-direct is revealing tangible information on settings for horticultural displays.

For wealthy Romans, gardens were a place to exercise the mind, for instance by strolling while conversing about philosophy or literature. The orator and philosopher Cicero famously wrote that if you have a garden and a library you have everything you need.

The type of plants chosen could reveal much about how cultured the owner was. From the writings of Roman authors, we can see that plane trees (which nowadays commonly line streets and walkways in parks) were a good choice. They offered shade in summer and were a way to show that one was versed in Greek philosophy: Aristotle and Plato’s famed philosophical schools were held in garden’s shaded by plane trees, as Plato referred to in his Phaedrus.

Fruit of the empire

Rome empire-building military expeditions abroad also resulted in new plants, or new cultivars (a plant variety produced by selective breeding) of known plants being introduced into Italy. Roman generals or provincial governors often came back to Italy with specimens that they planted in their gardens. For example, Lucius Vitellius the Elder, the father of Emperor Vitellius, planted several figs varieties in his rural villa estate near Rome that he had encountered while governor of Syria. In this way, gardens could also become a sort of microcosm of Rome’s empire, with plants from different territories.

Horticultural display of grafted fruit trees and other plants reproduced by layering might have characterised the large garden of the House of Queen Caroline – named in the 19th century after the queen of Naples and sister of Napoleon Bonaparte, Caroline, who visited during its initial excavation. I am currently excavating the site in Pompeii in collaboration with colleagues from Cornell University. Here wide walkways seem to have separated the regularly spaced plantings, an indication that it was not a commercial orchard but a garden in which horticultural productivity was an important part of the pleasure the garden was meant to offer.

Committed to exercise

Walking in their gardens was a serious exercise for many wealthy Romans. Medical works such as the de Medicina by the encyclopedist Aulus Cornelius Celsus, written in the first century AD, give specific indications about the daily exercise physicians recommended: one Roman mile, or 1,000 paces.

Some gardens even came with exercise advice inscribed in them detailing how many laps a person needed to cover. One such inscription from Rome once stood in an ancient orchard. It advised that to cover one mile one needed to go along the path back and forth five times.

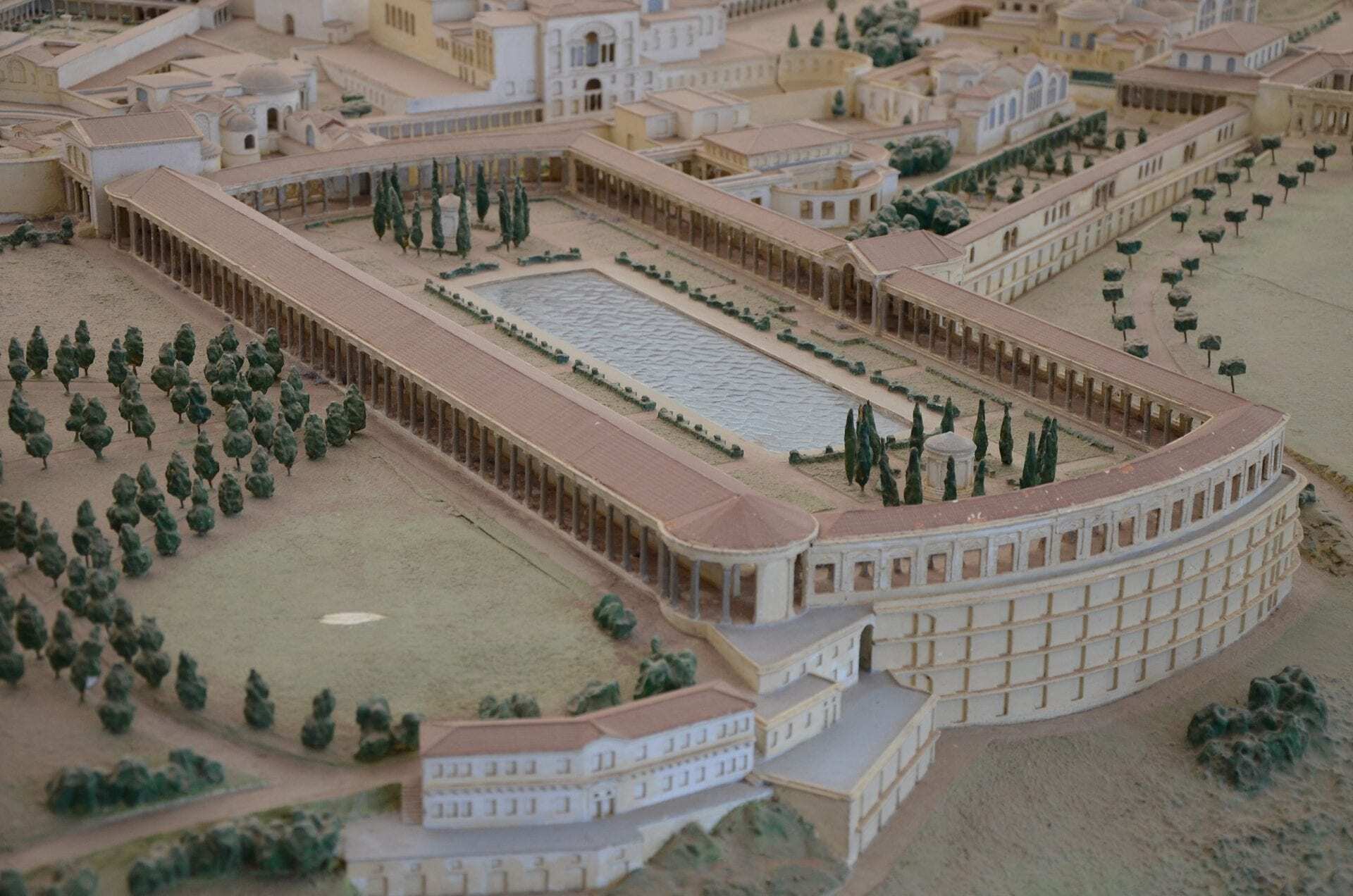

In Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli, Italy, a similar inscription was found in the Poikilé, the large four-sided portico enclosing a garden with a central pool. The north side of the Poikilé was a double portico, with circular spaces at both ends to allow one to do laps: this was where the emperor could walk sheltered from the elements. Thus, Hadrian could either take exercise in the open air, in the central garden, or under the roof of the double portico.

All this may suggest that the stereotype associating ancient Romans with excessive drinking and eating is undeserved. But, for wealthy individuals, moving about in a chariot or being carried around in a litter (a “vehicle” without wheels) by slaves in hippodrome-gardens (they were shaped like an elongated U and imitated the shape of the chariot-racing stadium) also counted as “exercising”. Indeed, there are two words in Latin texts for the daily walk: ambulatio, “walking about”, and gestatio, “being carried about”.

Such walking was the pastime of those who owned impressive townhouses or luxurious villas in the country or by the sea. But shrewd politicians such as the Emperor Augustus, who ruled from 27 BC to 14 AD, included gardens among the public building projects they financed. They understood that improving living standards by providing ordinary people with a green oasis to escape Rome’s crowded streets and cramped accommodation was a great way to gain popularity. Augustus opened to the public the groves and walks which surrounded the magnificent Mausoleum he had built, and before him, Caesar had willed to the people of Rome his large pleasure park (Horti).

Following the Roman dichotomy between amoenitas (delightfulness) and utilitas (usefulness), scholars traditionally class gardens as either utilitarian or pleasure gardens, but this binary choice does not fully capture the essence of Roman garden culture. Roman gardens were complex physical and ideological spaces. They represented wealth and contributed to wealth and they showed off horticultural skills through aesthetics as well as their ability to produce food.

Header Image Credit : Carole Raddato

![]()