Some 240 million years ago, a dolphin-like ichthyosaur ripped to pieces and swallowed another marine reptile only a little smaller than itself.

Then it almost immediately died and was fossilized, preserving the first evidence of megapredation, or a large animal preying on another large animal. The fossil, discovered in 2010 in southwestern China, is described in a paper published Aug. 20 in the journal iScience.

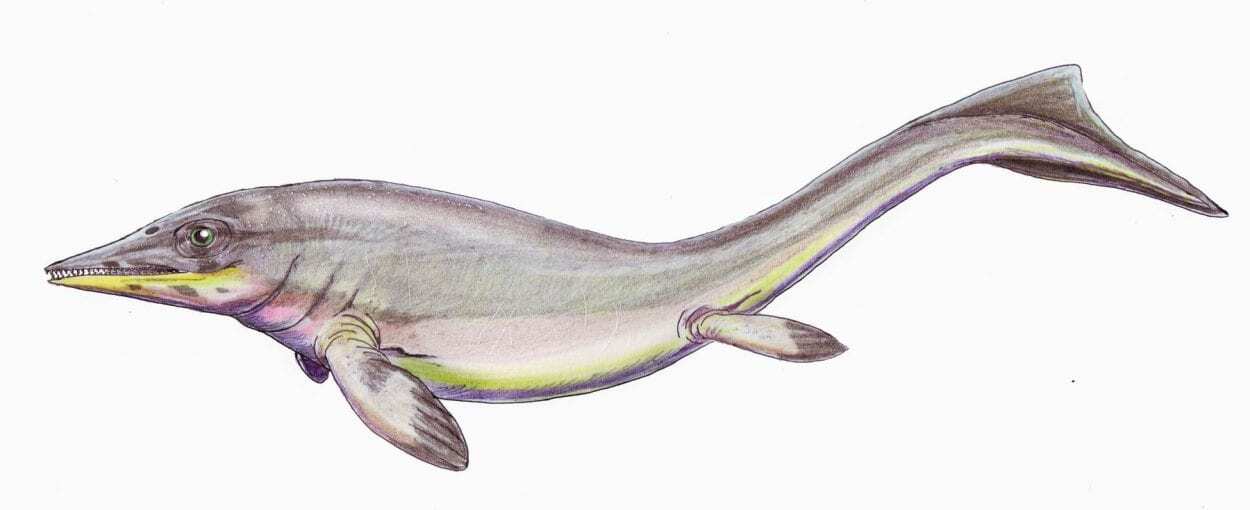

The ichthyosaurs were a group of marine reptiles that appeared in the oceans after the Permian mass extinction, about 250 million years ago. They had fish-like bodies similar to modern tuna, but breathed air like dolphins and whales. Like modern orca or great white sharks, they may have been apex predators of their ecosystems, but until recently there has been little direct evidence of this.

When a specimen of the ichthyosaur Guizhouichthyosaurus was discovered in Guizhou province, China in 2010, researchers noticed a large bulge of other bones within the animal’s abdomen. On examination, they identified the smaller bones as belonging to another marine reptile, Xinpusaurus xingyiensis, which belonged to a group called thalattosaurs. Xinpusaurus was more lizard-like in appearance than an ichthyosaur, with four paddling limbs.

“We have never found articulated remains of a large reptile in the stomach of gigantic predators from the age of dinosaurs, such as marine reptiles and dinosaurs,” said Ryosuke Motani, professor of earth and planetary sciences at the University of California, Davis, and coauthor on the paper. “We always guessed from tooth shape and jaw design that these predators must have fed on large prey but now we have direct evidence that they did.”

The Guizhouichthyosaurus was almost five meters (15 feet) long, while the researchers calculate its prey was about four meters (12 feet) long, although thalattosaurs had skinnier bodies than ichythyosaurs. The predator’s last meal appears to be the middle section of the thalattosaur, from its front to back limbs. Interestingly, a fossil of what appears to be the tail section of the animal was found nearby.

Predators that feed on large animals are often assumed to have large teeth adapted for slicing up prey. Guizhouichthyosaurus had relatively small, peg-like teeth, which were thought to be adapted for grasping soft prey such as the squid-like animals abundant in the oceans at the time. However, it’s clear that you don’t need slicing teeth to be a megapredator, Motani said. Guizhouichthyosaurus probably used its teeth to grip the prey, perhaps breaking the spine with the force of its bite, then ripped or tore the prey apart. Modern apex predators such as orca, leopard seals and crocodiles use a similar strategy.

Header Image Credit : Dmitry Bogdanov