A new study by Alicante University reveals the feeding pattern of the most common primate of the fossil registry of the African Pleistocene.

A study published in the Journal of Human Evolution reveals for the first time the diet of fossil baboon Theropithecus oswaldi discovered in the Victoria Cave in Cartagena (Murcia), the only site in Europe with remains of this primate, which is four million years old and came from eastern Africa.

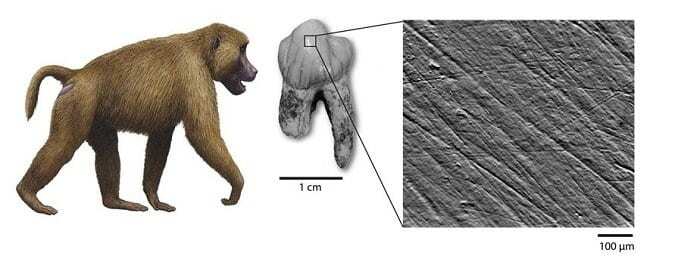

The new work analyses the diet of this primate based on its sole European fossil remains and thanks to the analysis of the oral micro-wear patterns on the teeth resulting from eating food. According to the conclusions, the feeding pattern of this guenon – the most common primate in the fossil registry of the Pleistocene in the African continent – would be different to that of baboon Theropithecus gelada, which is phylogenetically currently the closest species to T. oswaldi. Baboon T. gelada, which lives in the Simien mountains in northern Ethiopia, usually feeds on fresh herbs and sprigs.

The work, headed by professors Laura Martínez and Alejandro Pérez-Pérez, from the Faculty of Biology of the University of Barcelona (UB), was also produced by expert from the Department of Biotechnology of the University of Alicante (UA) Alejandro Romero, as well as experts from the Faculty of Earth Sciences and the Faculty of Psychology of the UV, from the Autonomous University of Barcelona, the Municipal Museum of Prehistory and Palaeontology of Orce (Granada) and George Washington University (USA).

Diet of the fossil baboon in the south of the Iberian Peninsula

According to UA researcher Alejandro Romero, “the analysis with electronic microscopy that we did of the enamel of the teeth from Theropithecus oswaldi revealed a good state of preservation, which made it possible to define oral micro-wear”. The pattern of micro-grooves that were observed on the enamel, adds Romero, “is a reflection of the abrasive nature of the food that was chewed. Therefore, when compared with models of primates with known diets, it is possible to deduce the type of feeding ecology of fossil species.”

In this sense, the analysis of the grooves caused to the vestibular side of the teeth resulting from eating these abrasive foods confirms that T. oswaldi specimens from the Victoria Cave “had to have a more abrasive diet than the current T. gelada, and more similar to the solid food-based diet of other primates, such as mangabeys (Cercocebus sp.) and baboons (Mandrillys sphinx), who eat fruits and seeds, some of them with hard coats, in wooded and semi-open ecosystems,” adds Laura Martínez from the Faculty of Biology of the UB.

However, other more recent studies based on observations of T. Gelada from the region of Guassa, also in Ethiopia, describe a more diverse diet, “with the presence of rhizomes and tubers during the most unfavourable season. “The difference found between T. oswaldi and T. gelada specimens – add study authors – indicates that the specialisation observed in current baboons could be derived from the fact that there were no fossils in their lineage. This could be a consequence of a regression in their ecological niche as an adaptation to ecosystems that were altered anthropically or as a result of climate change.”

Victoria Cave: the long journey of the African baboon

The Theropithecus genus expanded beyond the Sahara desert, from the east to the north and south of the African continent. Their evolutionary lineage, which is also currently present in some geographical areas of Europe and Asia, came very close to disappearing some 500,000 years ago. Today, it would only be represented by the Theropithecus gelada species, a baboon that basically feeds on herbs and has an ecological profile closer to herbivores than primates.

In 1990, the digging campaign led by palaeontologist Josep Gibert found the first fossil remain, a tooth of Theropithecus oswald (Journal of Human Evolution, 1995), in the Victoria Cave (Cartagena). This karstic cave – an old manganese mine – has provided fossil remains of close to 100 species of vertebrates and is one of the few European sites from the Lower Pleistocene that has human remains. Outside the African continent, the fossil registry of baboon fossils is very scarce, as other remains have only been found in Ubeidiya (Israel) and Minzapur (India).

The new fossil remains of T. oswaldi – with between 900,000 and 850,000 years of age – were recovered by a team from the Faculty of Earth Sciences of the UB. The presence of this African guenon in the south-east of the Iberian Peninsula strengthens the hypothesis of dispersion models of fauna from the African continent in Europe during the Pleistocene through the Strait of Gibraltar.

The study published in Journal of Human Evolution is framed within the Paleobaboon Research Project, which analyses the dental and cranial adaptations of primates from the papionine tribe as an analogous model of the evolution of the Hominini lineage, who they shared a common geographical space with at similar dates.