Carbon is an essential building block for all living things on Earth and plays a vital role in many of the geologic processes that shape life on the planet, including climate change and ocean acidification.

But the total amount of carbon on Earth remains a mystery, because more than 90% of Earth’s carbon is inaccessible to direct observation and measurement, deep within the planet at extreme temperature and pressure.

Now, a team of scientists reports March 30 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences how carbon behaved during Earth’s violent formative period. The findings can help scientists understand how much carbon likely exists in the planet’s core and the ways it influences chemical and dynamic activities that shape the world, including the convective motion that powers the magnetic field that protects Earth from cosmic radiation.

The research team included Elizabeth Cottrell, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History curator of rocks and ores; former museum fellow Marion Le Voyer; Harvard University professor and former museum fellow Rebecca Fischer; Yale University’s Kanani Lee; and Carnegie Institution for Science’s late Erik Hauri, to whom the paper is dedicated.

Earth’s core is comprised mostly of iron and nickel, but its density indicates the presence of other lighter elements, such as carbon, silicon, oxygen, sulfur or hydrogen. It has been long suspected that there is a tremendous reservoir of carbon hidden in the core. In an effort to quantify the amount of carbon in the core, the research team turned to laboratory experiments that mimic the conditions of the Earth’s formation to understand how carbon got there in the first place.

“To understand present day Earth’s carbon content, we went back to our planet’s babyhood, when it accreted from material surrounding the young sun and eventually separated into chemically distinct layers–core, mantle and crust,” Fischer said. “We set out to determine how much carbon entered the core during these processes.”

This was accomplished by lab experiments that compared carbon’s compatibility with the silicates that comprise the mantle to its compatibility with the iron that comprises the core. These lab experiments were conducted under the extreme pressures and temperatures found deep inside the Earth during its formative period.

“We found that more carbon would have stayed in the mantle than we previously suspected,” Cottrell said. “This means the core must contain significant amounts of other lighter elements, such as silicon or oxygen, both of which become more attracted to iron at high temperatures.”

Despite this surprising discovery, the vast majority of Earth’s total carbon inventory does likely exist down in the core. Even so, it only makes up a negligible fraction of the core’s overall composition.

Tim McCoy, the museum’s curator of meteorites who was not involved in the study, said, “This study provides compelling evidence that carbon-rich meteorites like those known from our collections delivered most of Earth’s carbon when our planet first formed, with only a small percentage of carbon perhaps delivered by late-impacting asteroids or comets.”

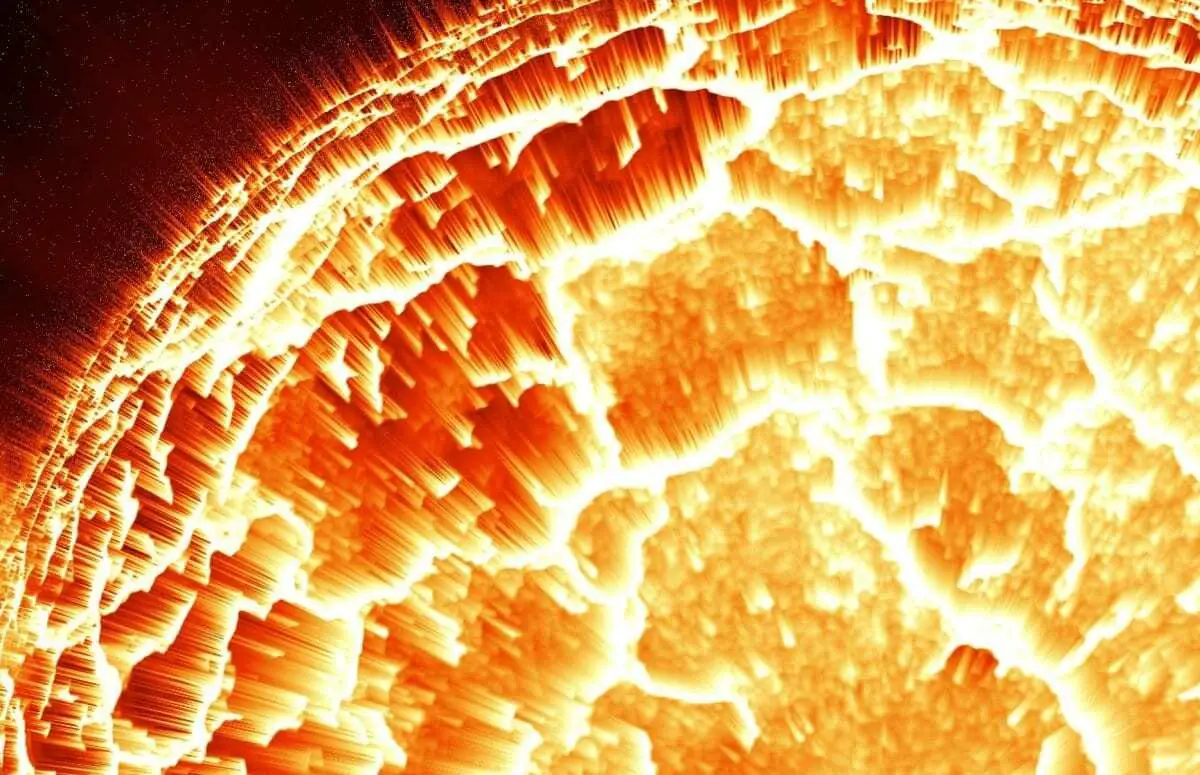

Header Image – Public Domain