A palette of colours on a silver plate: that is what the world’s first colour photograph looks like. It was taken by French physicist Edmond Becquerel in 1848. His process was empirical, never explained, and quickly abandoned.

A team at the Centre de recherche sur la conservation (CNRS/Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle/Ministère de la Culture) has now shone a light on this, in collaboration with the SOLEIL synchrotron and the Laboratoire de Physique des Solides (CNRS/Université Paris-Saclay). The colours obtained by Edmond Becquerel were due to the presence of metallic silver nanoparticles, according to their study published on 30 March 2020 in Angewandte Chemie International Edition.

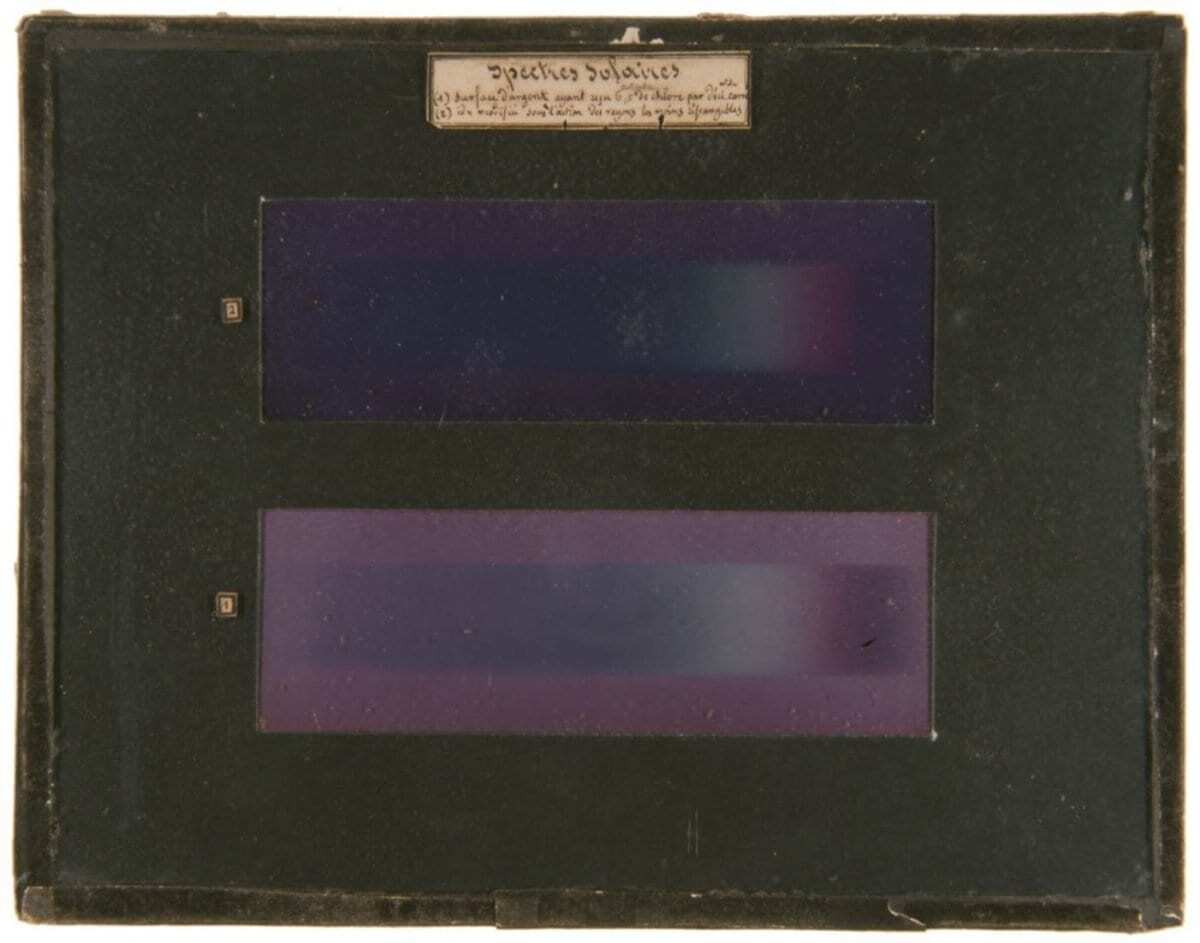

In 1848, in the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, Edmond Becquerel managed to produce a colour photograph of the solar spectrum. These photographs, which he called “photochromatic images”, are considered to be the world’s first colour photographs. Few of these have survived1 because they are light-sensitive and because very few were produced in the first place. It took the introduction of other processes2 for colour photography to become popular in society.

For more than 170 years, the nature of these colours has been debated in the scientific community, without resolution. Now we know the answer, thanks to a team at the Centre de recherche sur la conservation (CNRS/Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle/Ministère de la Culture) in collaboration with the SOLEIL synchrotron and the Laboratoire de Physique des Solides (CNRS/Université Paris-Saclay). After having reproduced Edmond Becquerel’s process to make samples of different colours, the team started by re-examining 19th century hypotheses in light of 21st century tools. If the colours were due to pigments formed during the reaction with light, we should have seen variations in chemical composition from one colour to another,which no spectroscopy method has shown. If they were the result of interference, like the shades of some butterflies, the coloured surface should have shown regular microstructures about the size of the wavelength of the colour in question. Yet no periodic structure was observed using electron microscopy.

However, when the coloured plates were examined, metallic silver nanoparticles were revealed in the matrix made of silver chloride grains — and the distributions of sizes and locations of these nanoparticles vary according to colour. The scientists assume that according to the light’s colour (and therefore its energy), the nanoparticles present in the sensitised plate reorganise: some fragment and others coalesce. The new configuration gives the material the ability to absorb all colours of light, with the exception of the colour that caused it: and therefore that is the colour that we see. Nanoparticles having properties related to colour is a phenomenon known to physicists as surface plasmons3, electron vibrations (here, those of the metallic silver nanoparticles) that propagate in the material. A spectrometer in an electron microscope measured the energies of these vibrations to confirm this hypothesis.

This work was supported by the SACRe programme at the Université PSL, the Observatoire des Patrimoines de Sorbonne Université and the CEA and CNRS’s national network for transmission electron microscopy and atom probe microscopy.

CNRS (Délégation Paris Michel-Ange)

Header Image – Edmond Becquerel, Solar spectra, 1848, photochromatic images, Musée Nicéphore Niépce, Chalon-sur-Saône.