Bats are famous for their sonar-based navigation. They use their extremely sensitive hearing for orientation, emitting ultrasound noises and receiving an image of their surroundings based on the echo.

Seba’s short-tailed bat (Carollia perspicillata), for example, finds the fruits that are its preferred food using this echolocation system. At the same time, bats also use their voices in a somewhat deeper frequency range to communicate with other members of their species. Seba’s short-tailed bats employ a vocal range for this purpose that is otherwise only found among songbirds and humans. Like humans, they produce sound through the larynx.

Together with his team, neuroscientist Julio C. Hechavarria from the Institute for Cell Biology and Neuroscience at Goethe University investigated brain activity preceding vocalisation in Seba’s short-tailed bats. The scientists were able to identify a group of nerve cells that create a circuitry from the frontal lobe to the corpus striatum in the interior of the brain. When this neural circuit fires off rhythmic signals, the bat emits a vocalisation about half a second later. The type of rhythm seemed to determine whether the bats were about to utter echolocation or communication vocalisations.

Since it is nearly impossible to make a prediction within half a second, the Frankfurt researchers trained a computer to test their hypothesis: The computer analysed the recorded sounds and the neural rhythm separately and attempted to make prognoses using the various rhythms. The result: in its predictions of echolocation versus communication vocalisations, the computer was correct about 80 percent of the time. Predictions were particularly accurate when considering signals from the frontal lobe, an area that in humans has been linked to action planning, among other functions.

The Frankfurt scientists argue that the rhythms they observed in the bat brain are similar to neural rhythms often recorded from the human scalp, and concluded that brain rhythms could be linked to sound production in mammals in general.

Julio Hechavarria: “For over 50 years, bats have served as an animal model for studying how the brain processes auditory stimuli and how human language develops. For the first time, we were able to show how distant brain regions in bats communicate with each other during vocalization. At the same time, we know that the corresponding brain networks are impaired in individuals who, for example, stutter as a result of Parkinson’s disease or emit involuntary noises due to Tourette syndrome. We therefore hope that by continuing to study vocal behaviour in bats, we can contribute to a better understanding of these human diseases.”

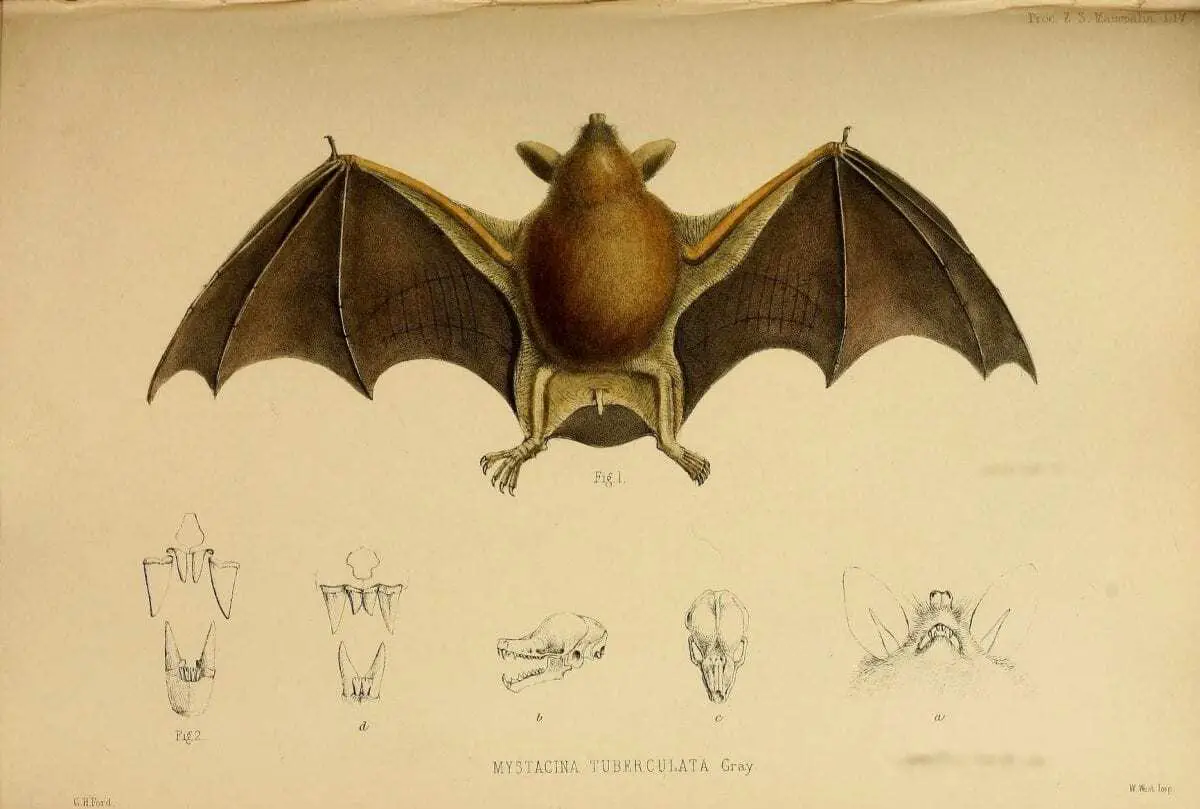

Short tailed bat – Credit : Zoological Society of London