Mead or “honey-wine” is a fermented honey drink with water that has been produced for thousands of years throughout Europe, Africa and Asia.

Mead – “fermented honey drink” – derives from the Old English meodu or medu, and Proto-Germanic, *meduz. The name has connections to Old Norse mjöðr, Middle Dutch mede, and Old High German metu, among others.

The earliest recorded evidence dates from 7000BC, where archaeologists discovered pottery vessels from the Neolithic village of Jiahu in Henan province, China that contained the chemical signatures of honey, rice and compounds normally associated with the process of fermentation.

Mead became present in Europe between 2800 to 1800BC during the European Bronze Age. Throughout this period, the Bell Beaker culture or short Beaker culture was producing the “All Over Ornamented (AOO)” and the “Maritime Type” beaker pottery. The beakers are suggested to have been produced primarily for alcohol consumption, with some examples of these pottery forms containing chemical signatures for mead production.

During the Golden Age of Ancient Greece, mead “hydromeli” proceeded wine and was a stable beverage of Grecian culture. Hydromeli was even the preferred tipple of Aristotle, in which he discussed mead in his Meteorologica.

The German classical scholar, W. H. Roscher suggested that mead was even the nectar or ambrosia of the Gods. He compared ambrosia to honey, with their power of conferring immortality due to the supposed healing and cleansing powers of honey, which is in fact anti-septic, and because fermented honey (mead) preceded wine as an entheogen in the Aegean world; on some Minoan seals, goddesses were represented with bee faces (compare Merope and Melissa).

This is supported in the archaic versions of the stories of the gods. The Orphists preserve a tale about the cruel guile of Zeus who surprised his father Kronos when he was drunk on the honey of wild bees and castrated him.

Mead “aquamulsum” or just “mulsum” was also common during the Imperial Roman era and came in various forms. Mulsum was a freshly made mixture of wine and honey (called a pyment today) or simply honey left in water to ferment; and conditum was a mixture of wine, honey and spices made in advance and matured (arguably more a faux-mead).

The Hispanic-Roman naturalist Columella gave a recipe for mead in De re rustica, around 60 BCE.

“Take rainwater kept for several years, and mix a sextarius of this water with a [Roman] pound of honey. For a weaker mead, mix a sextarius of water with nine ounces of honey. The whole is exposed to the sun for 40 days, and then left on a shelf near the fire. If you have no rainwater, then boil spring water.”

Alcoholic drinks made from honey would become very popular within the Early Middle Ages and Medieval Europe. This was especially so among the Native Brythonic cultures, Anglo-Saxons, Germans, and Scandinavians. However, wines remained the preferred beverage in warmer climates in what is now Italy, Spain and France.

Anglo-Saxon literature such as Mabinogion, Beowulf and the Brythonic writings of the Welsh poet Taliesin (who wrote the Kanu y med or “Song of Mead ) describe mead as the drink of Kings and Thanes. In the Old English epic poem Beowulf set in Scandinavia, Beowulf comes to the aid of Hrothgar, the king of the Danes, whose mead hall in Heorot has been under attack by a monster known as Grendel.

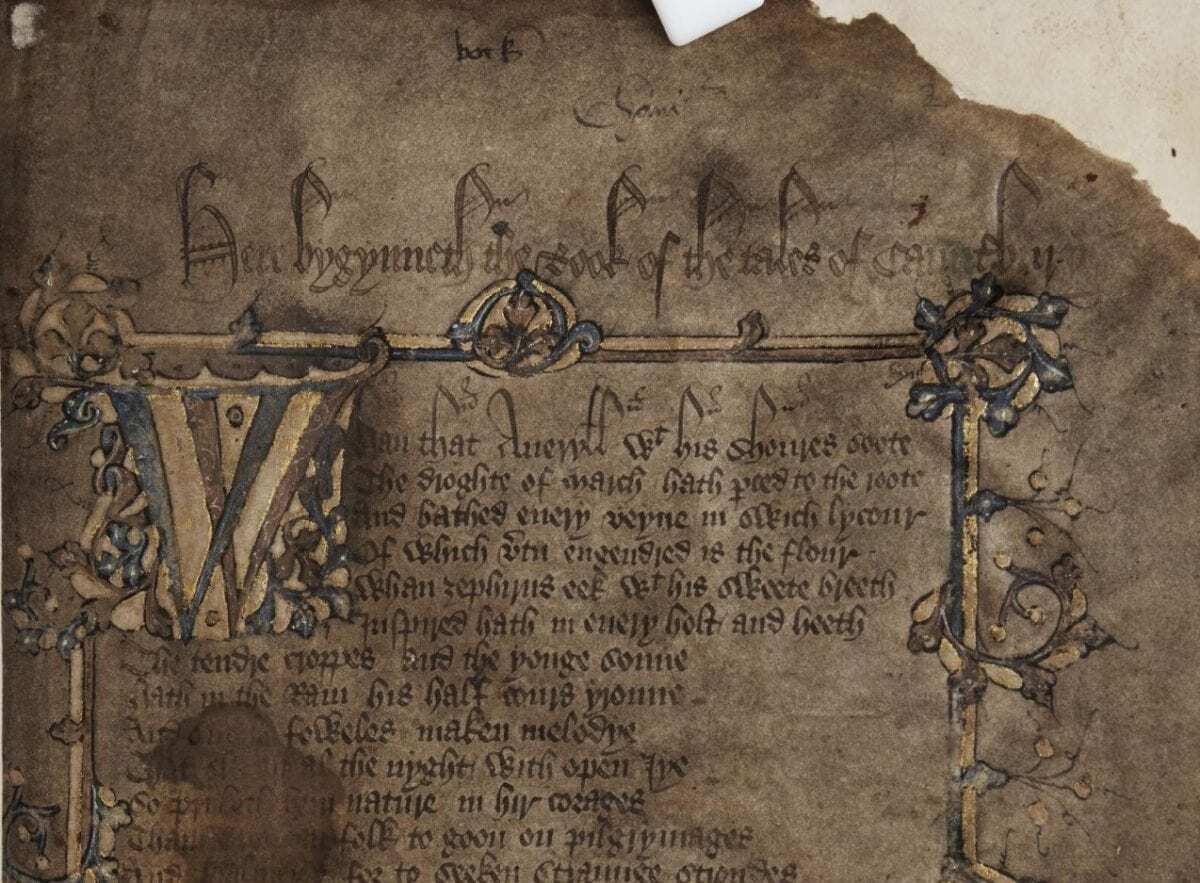

In Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales – The Miller’s Tale, mead is described as the draught of townfolk and used to court a fair lady. Chaucer also makes mention of spiking his claret with honey.

“He sent her sweetened wine and well-spiced ale

And waffles piping hot out of the fire,

And, she being town-bred, mead for her desire

For some are won by means of money spent

And some by tricks and some by long descent.”

In later years, tax and regulation drove commercial mead out of popularity with beer and wine becoming the predominant alcoholic drinks. Some monasteries in England and Wales kept up the traditions of mead-making as a by-product of beekeeping but with the dissolution of the monasteries in the 16th century mead all but disappeared.

Finally, when West Indian sugar began to be imported in quantity (from the 17th century), there was less incentive to keep bees to sweeten foods and the essential honey to ferment mead became scarcer across Europe leading to its decline.