Chlamydia are infamous for causing sexually transmitted infections in humans and animals or even amoeba.

An international team of researchers have now discovered diverse populations of abundant Chlamydia living in deep Arctic ocean sediments. They live under oxygen-devoid conditions, high pressure and without an apparent host organism. Their study, published in Current Biology today, provides new insights into how Chlamydia became human and animal pathogens.

Chlamydia and related bacteria, collectively called ‘Chlamydiae’, and all studied members of this group depend on interactions with other organisms to survive. Chlamydiae specifically interact with organisms such as animals, plants and fungi, and including microscopic organisms like amoeba, algae and plankton.

Chlamydiae spend a large part of their lives inside the cells (also one cell?) of their hosts, humans, but also of koala bears. Most knowledge about Chlamydiae is based on studies of pathogenic lineages in the lab. But do Chlamydiae also exist in other environments? The new research published in Current Biology shows that Chlamydiae can be found in the most unexpected of places.

Growing in 3 km deep ocean

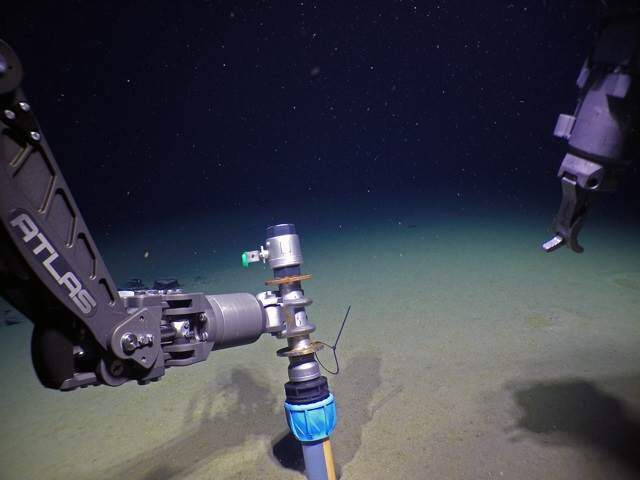

An international group of researchers report the discovery of numerous new species of Chlamydiae growing in deep Arctic Ocean sediments, in absence of any obvious host organisms. The researchers had been exploring microbes that live over 3 km below the ocean surface and several meters into the ocean seafloor sediment during an expedition to Loki’s Castle, a deep-sea hydrothermal vent field located in the Arctic Ocean in-between Iceland, Norway, and Svalbard.

This environment is devoid of oxygen and macroscopic life forms. Unexpectedly, the research team came across highly abundant and diverse relatives of Chlamydia. “Finding Chlamydiae in this environment was completely unexpected, and of course begged the question what on earth were they doing there?” says Jennah Dharamshi from Uppsala University in Sweden and lead author of the study.

The team of researchers had been working with metagenomic data – obtained by collectively sequencing the genetic material of all organisms that live in an environment – which doesn’t rely on growing organisms in the lab. “The vast majority of life on earth is microbial, and currently most of it can’t be grown in the lab,” explains Thijs Ettema, professor in Microbiology at Wageningen University & Research in The Netherlands who led the work. “By using genomic methods, we obtained a more clear image on the diversity of life. Every time we explore a different environment, we discover groups of microbes that are new to science. This tells us just how much is still left to discover”.

Impact on the ecology in oxygen free ecosystem

Thijs Ettema’s team discovered that one of these new groups of Chlamydiae is closely related to Chlamydia that cause disease in humans and other animals. “Finding that Chlamydia have marine sediment relatives, has given us new insights into how chlamydial pathogens evolved.” says Jennah Dharamshi. Some of these new groups of Chlamydiae are exceptionally abundant in these ocean sediments, and in some cases are even the dominant bacteria present. The researchers suggest this means that Chlamydiae have a significant impact on the ecology in this oxygen-devoid ecosystem. In fact, they also identified Chlamydiae in a myriad of additional environments. “Chlamydiae have likely been missed in many prior surveys of microbial diversity”, suggests Wageningen researcher Daniel Tamarit. “This group of bacteria could be playing a much larger role in marine ecology than we previously thought.”

‘They require components from other microbes’

Unfortunately, the researchers have as of yet been unable to grow these Chlamydiae or take images of them. “Even if these Chlamydiae are not associated with a host organism, we expect that they require compounds from other microbes living in the marine sediments. Additionally, the environment they live in is extreme, without oxygen and under high pressure, this makes growing them a challenge,” explains Thijs Ettema. Nevertheless, the discovery of Chlamydiae in this unexpected environment challenges the current understanding of the biology of this ancient group of bacteria, and hints that additional Chlamydiae are awaiting to be discovered.

Wageningen University & Research

Header Image – Push coring of deep sea sediments with the remotely operated vehicle Ægir at 2800 meters depth in the Norwegian-Greenland sea during K G Jebsen Centre for Deep Sea research expedition 2018 Credit: K G Jebsen Centre for Deep Sea Research, University of Bergen.

Header Image – Public Domain