A team led by UC Riverside geologists has discovered the first ancestor on the family tree that contains most familiar animals today, including humans.

The tiny, wormlike creature, named Ikaria wariootia, is the earliest bilaterian, or organism with a front and back, two symmetrical sides, and openings at either end connected by a gut. The paper is published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The earliest multicellular organisms, such as sponges and algal mats, had variable shapes. Collectively known as the Ediacaran Biota, this group contains the oldest fossils of complex, multicellular organisms. However, most of these are not directly related to animals around today, including lily pad-shaped creatures known as Dickinsonia that lack basic features of most animals, such as a mouth or gut.

The development of bilateral symmetry was a critical step in the evolution of animal life, giving organisms the ability to move purposefully and a common, yet successful way to organize their bodies. A multitude of animals, from worms to insects to dinosaurs to humans, are organized around this same basic bilaterian body plan.

Evolutionary biologists studying the genetics of modern animals predicted the oldest ancestor of all bilaterians would have been simple and small, with rudimentary sensory organs. Preserving and identifying the fossilized remains of such an animal was thought to be difficult, if not impossible.

For 15 years, scientists agreed that fossilized burrows found in 555 million-year-old Ediacaran Period deposits in Nilpena, South Australia, were made by bilaterians. But there was no sign of the creature that made the burrows, leaving scientists with nothing but speculation.

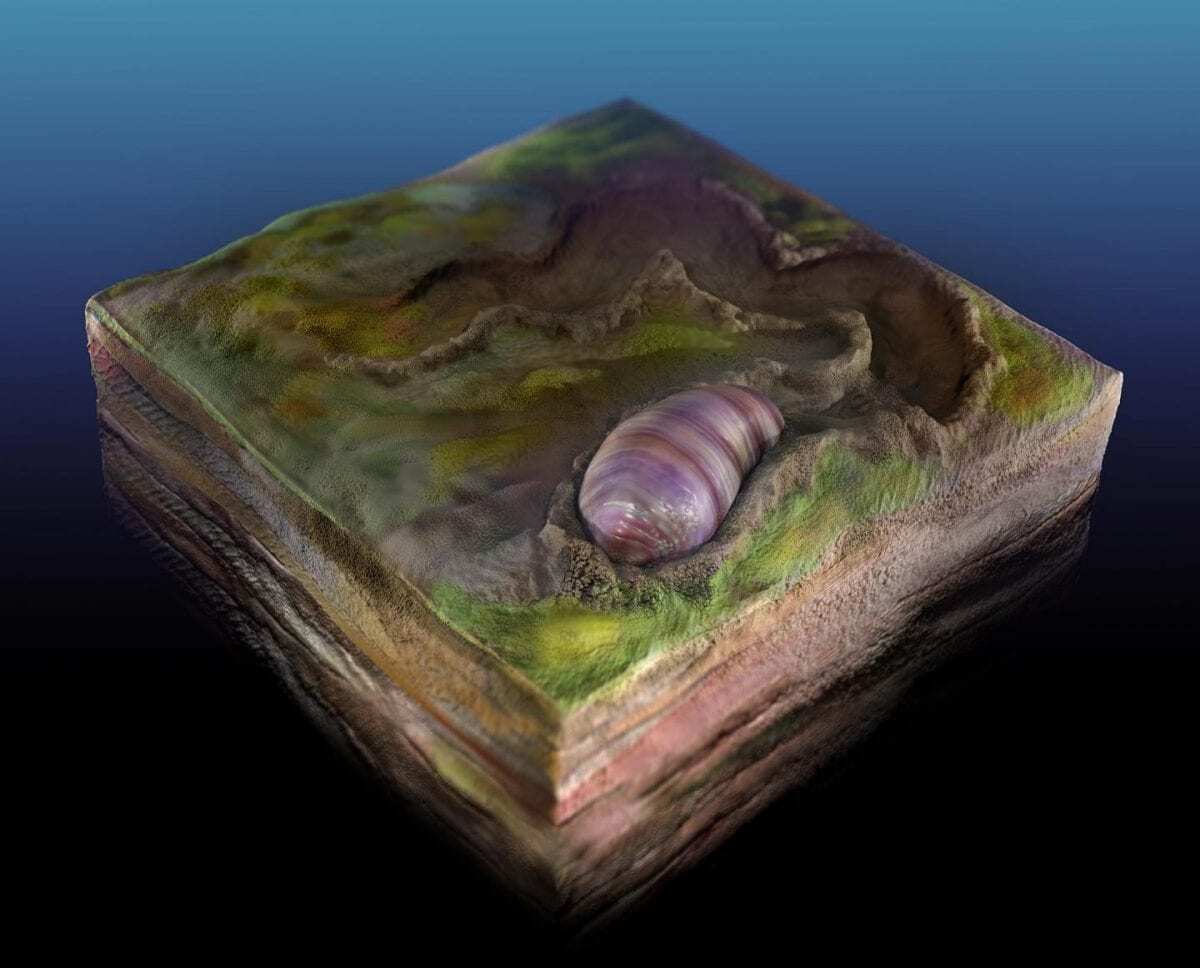

Scott Evans, a recent doctoral graduate from UC Riverside; and Mary Droser, a professor of geology, noticed miniscule, oval impressions near some of these burrows. With funding from a NASA exobiology grant, they used a three-dimensional laser scanner that revealed the regular, consistent shape of a cylindrical body with a distinct head and tail and faintly grooved musculature. The animal ranged between 2-7 millimeters long and about 1-2.5 millimeters wide, with the largest the size and shape of a grain of rice — just the right size to have made the burrows.

“We thought these animals should have existed during this interval, but always understood they would be difficult to recognize,” Evans said. “Once we had the 3D scans, we knew that we had made an important discovery.”

The researchers, who include Ian Hughes of UC San Diego and James Gehling of the South Australia Museum, describe Ikaria wariootia, named to acknowledge the original custodians of the land. The genus name comes from Ikara, which means “meeting place” in the Adnyamathanha language. It’s the Adnyamathanha name for a grouping of mountains known in English as Wilpena Pound. The species name comes from Warioota Creek, which runs from the Flinders Ranges to Nilpena Station.

“Burrows of Ikaria occur lower than anything else. It’s the oldest fossil we get with this type of complexity,” Droser said. “Dickinsonia and other big things were probably evolutionary dead ends. We knew that we also had lots of little things and thought these might have been the early bilaterians that we were looking for.”

In spite of its relatively simple shape, Ikaria was complex compared to other fossils from this period. It burrowed in thin layers of well-oxygenated sand on the ocean floor in search of organic matter, indicating rudimentary sensory abilities. The depth and curvature of Ikaria represent clearly distinct front and rear ends, supporting the directed movement found in the burrows.

The burrows also preserve crosswise, “V”-shaped ridges, suggesting Ikaria moved by contracting muscles across its body like a worm, known as peristaltic locomotion. Evidence of sediment displacement in the burrows and signs the organism fed on buried organic matter reveal Ikaria probably had a mouth, anus, and gut.

“This is what evolutionary biologists predicted,” Droser said. “It’s really exciting that what we have found lines up so neatly with their prediction.”

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA – RIVERSIDE

Header Image – Artist’s rendering of Ikaria wariootia. Credit : Sohail Wasif/UCR