Archaeologists have found a mass grave at Thornton Abbey in Lincolnshire, England.

This countryside priory appears to have had a medieval hospital that was overwhelmed by the Black Death. This forced them to dig the mass grave, which contains at least 48 people.

The Black Death devastated England from 1348 to 1349 AD, killing up to half of the population in less than 2 years. Large cities had to dig mass graves to cope. However, these are unknown in small rural communities like Thornton, making this site unique.

The mass grave there contains at least 48 people, including 21 children, buried over the course of a few days in the 15th century. This catastrophic event was due to the Black Death, as analysis of 16 people’s teeth revealed the DNA of the disease pathogen Yersinia pestis.

This suggests normal institutions were overwhelmed by the Black Death, forcing people to turn to the nearby abbey and associated hospital as a last resort. However, this was also unable to cope, leading to the creation of the mass grave.

Despite the catastrophic circumstances, the dead were still buried with respect; each was carefully placed and wrapped with a burial shroud. It seems even in the midst of the disaster, the community still took care of each other.

A unique find

The Black Death devastated 15th century England, killing up to half of the population in less than 2 years. Whilst large cities had to dig mass graves, these are unknown in small, rural communities. At least, until the discovery of a mass burial at Thornton Abbey, in the Lincolnshire countryside. This burial contains 48 bodies, which have now been analysed by an international team of archaeologists. Their research suggests people turned to a hospital at the abbey for help during the Black Death, as other institutions struggled to cope. However, the hospital was also overwhelmed, so dug the mass grave. These findings, published in Antiquity, highlights how the Black Death devastated small communities.

Thornton Abbey

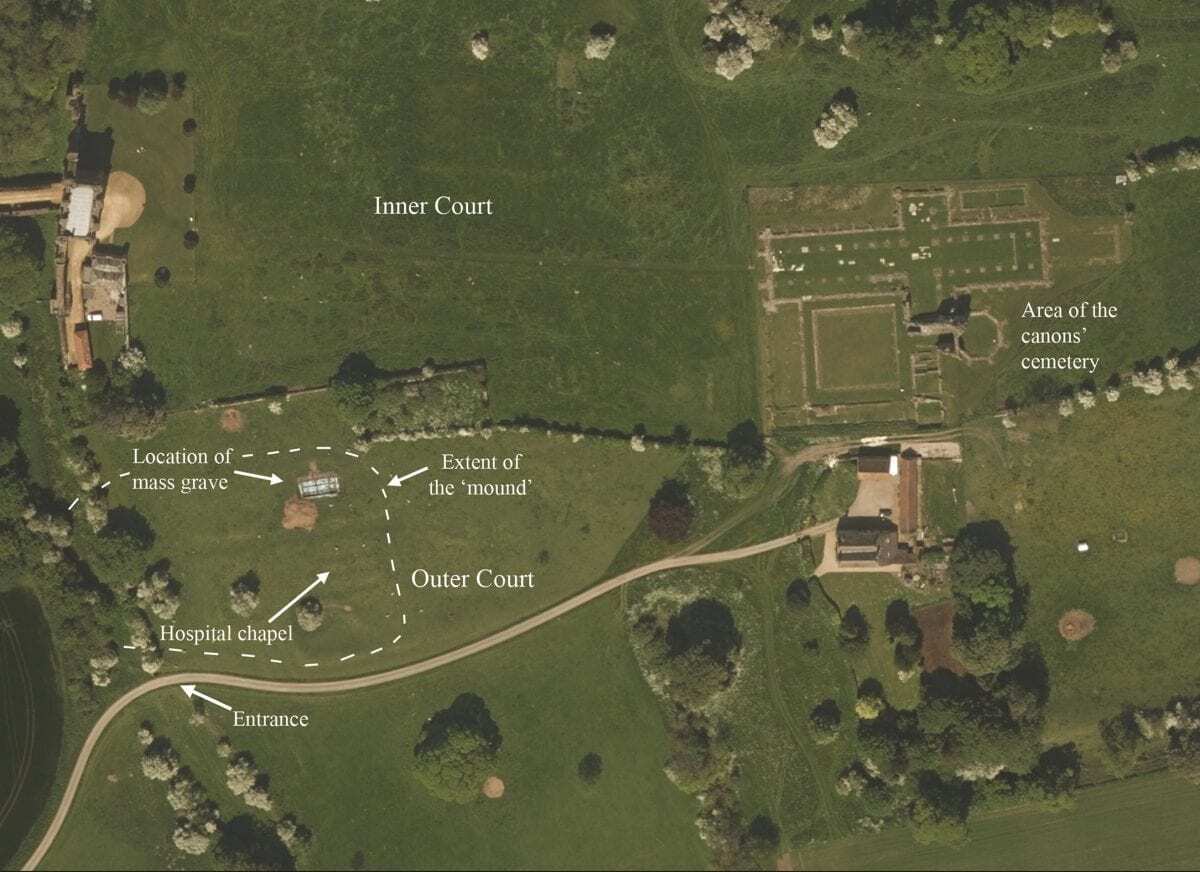

Thornton Abbey in Lincolnshire founded in 1139, it prospered due to its involvement with the local wool trade, becoming one of the richest monasteries until Henry VIII closed it down in the 1500s. In 2011, archaeologists from the University of Sheffield began a systematic survey of the abbey, revealing earthworks on the edge of the site. These were first thought to be the remains of a mansion built after the monastery was closed. However, excavations did not reveal a mansion. Instead, archaeologists found 48 human skeletons.

A mass grave pit

The mass grave at Thornton Abbey represents a catastrophe. The 48 people were buried over a short duration, possibly only a few days, representing a high percentage of the local population dying off quickly. Victims from all age ranges are represented, except for the very young.

However, this was likely because their softer bones were not preserved in the harsh soil. As such, there may have been many more people buried in the grave. What could cause such a catastrophe? Radiocarbon dating placed this burial within the timeframe of the Black Death. The archaeologists’ suspicions were confirmed by analysis of the molars of 16 individuals, which contain DNA from the pathogen responsible for the disease. Notably, the strain from Thornton is most closely related to those from mass graves in London, suggesting it was part of the same outbreak.

A 15th-century tragedy

It seems that Thornton Abbey was inundated with plague victims, to the point they could no longer keep up with the burials. Church records indicate a hospital of St James outside of the walls of the monastery, part of which has since been excavated by archaeologists, which may have been the destination of the sick. So why were so many people heading to this hospital? Records suggest many local institutions were overwhelmed, with many also suffering at the hands of the plague. At Meux Abbey, 18 km from Thornton, 80% of the monks died. Faced with failing local resources, the hospital may have been the only option for many local people.

The community in the face of danger

Although the resources of Thornton Abbey were stretched thin, they still took care to bury people as best they could. The position of individuals indicates they were wrapped in a burial shroud and carefully positioned side by side, so as not to overlap. In Medieval England, a proper Christian burial was vital, so this care in death was likely seen as just as important as any healthcare for the sick. In fact, it may have been what most people were traveling to the Abbey for, with little hope for recovery. As such, this discovery highlights both the devastation rural areas suffered from the Black Death but also sheds light on how people rallied together in the face of it.

The article is published in Antiquity Volume 94, Number 373: X–X https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.213

Header Image – A close up of part of the mass grave at Thornton, showing how the deceased were carefully positioned and placed in an organised manner without any overlap Credit: University of Sheffield)