Today the northern region of Sudan that borders with Egypt is mostly desert. But this part of the Nile’s valley was once home to a powerful African civilisation called Kush.

It traded gold and the products of inner Africa to Egypt and the Mediterranean world beyond. Kush was a major power in this region for over 2000 years, reaching its largest extent when it conquered Egypt and ruled as its 25th Dynasty from about 725-653 BCE.

In the years 300 BCE to 300 CE, Kush was ruled from the capital of Meroe. The city, which is today a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was located along the Nile about 100 miles north of modern-day Khartoum, the capital of Sudan. Other regions of Kush remained important, however. These included the older capital region of Napata, which centred on the “holy mountain” of Jebel Barkal and included the nearby pyramid cemetery of El-Kurru.

There were a number of temples and other sacred sites in Kush. And, as our ongoing research in El-Kurru has documented, visitors to these sites had one particular religious ritual that may strike some as strange: they carved graffiti in important and sacred places.

These graffiti can still be seen today at several sacred sites in what was the kingdom of Kush – on a pyramid and in a temple at El-Kurru, at a seasonal pilgrimage centre called Musawwarat es-Sufra, and in the Temple of Isis at Philae, at the border with Egypt.

We’re the curators of an exhibition detailing the recently discovered graffiti from El-Kurru. The exhibition is on view at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology at the University of Michigan until March 2020. It features photographs, text, and interactive media presentations that unpack the practice and its importance in Kushite society. A catalogue written in conjunction with the exhibition presents selected examples of graffiti from the Nile valley and beyond, including the ancient Roman city of Pompeii.

We are all accustomed to understanding ancient cultures almost entirely through the activities of the powerful elite and the art they left behind in their palaces, temples, and tombs. But that creates a distorted a picture of ancient life – as distorted as such a picture would be today. The graffiti featured in this exhibition allow a glimpse into some of the activities of non-elite people and their religious devotion to particular places. It’s a reminder that society is more than the elite and powerful.

Marking place and time

The graffiti at El-Kurru were discovered by a Kelsey Museum archaeological excavation, on a pyramid and in an underground temple at the site. El-Kurru was a royal cemetery for the kings of the Napatan dynasty, who ruled Egypt as the 25th dynasty. But the graffiti date to several hundred years after the kings’ rule. By this time the pyramids and funerary temple were partially abandoned, yet people were visiting the site and carving graffiti.

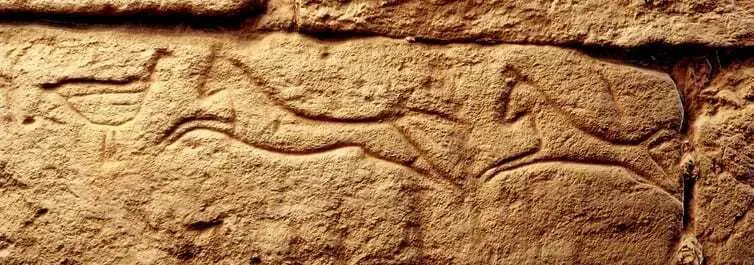

The graffiti include clear symbols of ancient Kush, like the ram that represented the local form of the god Amun, and a long-legged archer who symbolised Kushite prowess in archery. There are also intricate textile designs as well as animals – beautiful horses, birds, and giraffes.

The most common marks are small round holes gouged in the stone. By analogy with modern practices, these are probably areas where temple visitors scraped the wall of the holy place to collect powdered stone that they would ingest to promote fertility and healing.

Preserving heritage

Another part of the exhibition focuses on the work we’re doing to preserve the graffiti. The graffiti are carved into soft sandstone that is slowly being eroded. El-Kurru is a windy, desert site prone to sandstorms; it also receives periodic heavy rainstorms that are strong enough to cause flooding. As the surface of the stone wears away from these climatic conditions, so do the graffiti.

It is always difficult to adequately protect archaeological sites like El-Kurru: preservation activities can be expensive, and there are ongoing risks not only from severe weather but also from modern visitors who often like to carve their names into ancient monuments. But preservation work is even harder in a country like Sudan, which has a fragile economy and is undergoing great social and political upheaval.

We’ve worked with the local community and taken multiple steps to help preserve the graffiti for the future, including physical conservation of the structures into which they are carved. This kind of work has included things like grouting cracks in the stone’s surface with a lime-based mortar. This keeps water from penetrating the cracks and causing the carved surface to detach. But in the exhibition we focus primarily on digital documentation and preservation of the graffiti.

Our goal for this part of the project was to create a very good record of the graffiti as they are now. We used a method called reflectance transformation imaging. This is a simple photographic technique in which the camera remains perfectly still, focused on a graffito, while about 50 digital photographs are taken. The photographer positions a bright light so that it shines across the surface from a different angle in each photo. Then, software is used to merge all the photographs. The resulting file allows the user, or viewer, to play light across the image from any angle.

There are two big benefits to this type of documentation. First, it is a form of virtual preservation: if the graffiti are lost or damaged in the future there will still be a good record. Second, the digital files allow people to study and enjoy the graffiti, even if they cannot visit the site. The ability to manipulate the lighting direction also means that the graffito can be studied in a way that is not possible with natural light.

This careful documentation of El-Kurru’s graffiti has enabled us to study and understand them in new ways. It has also made it possible to share them with others, including other scholars, to explore their history and meaning. Although many of the graffiti remain mysterious, our ongoing work provides insight on life beyond the elite in ancient Kush: on their religious beliefs, their mobility, and on the importance of certain cultural symbols – even if we don’t yet know what they all mean.

Written by:

Suzanne Davis – Assoc. Curator of Conservation, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology; Director of Conservation for the International Kurru Archaeological Project, University of Michigan

Geoff Emberling – Associate Research Scientist in Archaeology, University of Michigan

Header Image Credit – Bertramz

![]()