Caledonia was the Latin name applied to the lands north of Roman Britannia, roughly corresponding to the territories of modern-day Scotland.

The region was inhabited by several ancient tribes, most notably the Caledonii, Vacomagi, Cornavii, Taexali, Creones, Venicones, Epidii, Lugi, Smertae and the Damnonii that the Romans nicknamed “Brittunculi” meaning “nasty little Britons”.

It is generally assumed that the tribes of Scotland remained completely autonomous, with the nationalistic notion of ancient Caledonii tribes holding firm against the might of the Roman war machine. But, archaeological evidence has shown that the low-land regional boundaries moved several times with many annexed tribes becoming subject to Roman rule for a time.

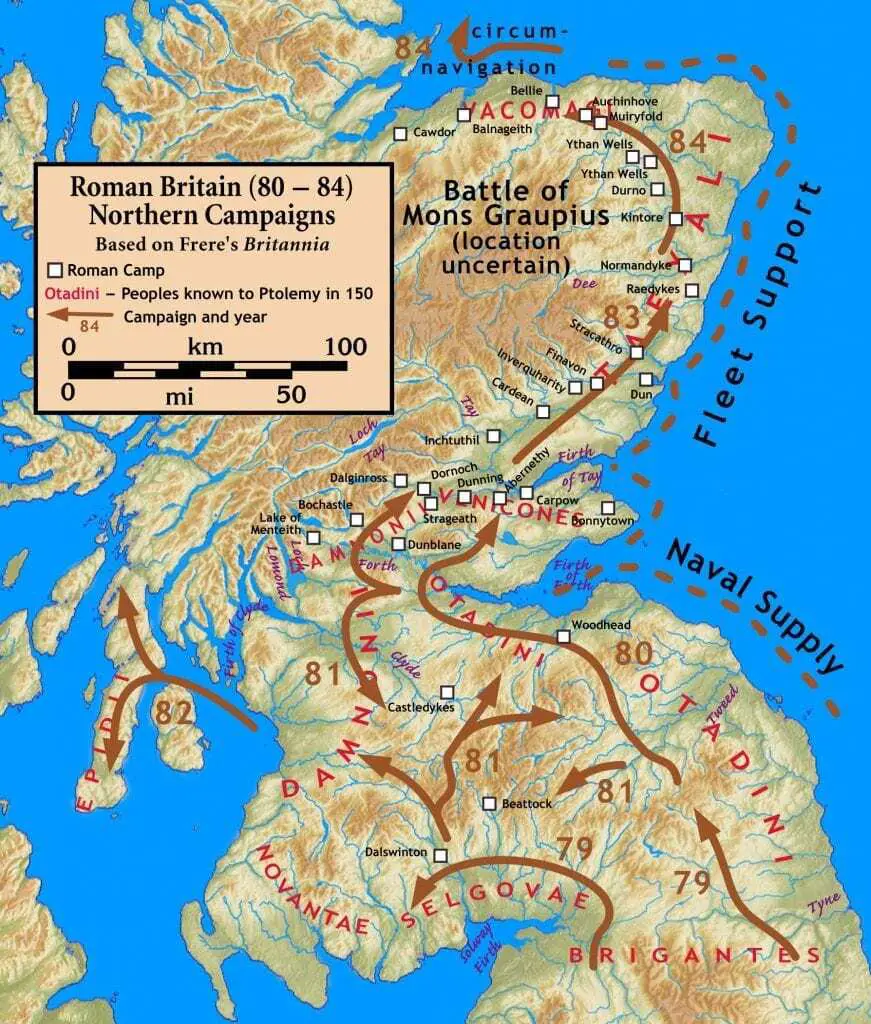

Incursions into central and northern Caledonia established chains of fortifications such as the Gask Ridge (built between 70-80 AD) and exploratory marching camps encircling the Fife, Angus, Tayside, Crampians and stretching as far north as the Moray Firth (next to the modern city of Inverness).

In the summer of 84AD, an army of 30,000 Caledonian warriors faced off against the 20,000 strong Roman invasion force led by General Gnaeus Julius Agricola at the Battle of Mons Graupius. According to the Roman historian Publius Cornelius Tacitus, 10,000 Caledonian lives were lost at the cost of only a fanciful 360 Roman auxiliary troops.

This resulted in the proclamation that Agricola had finally subdued resistance to Roman rule across all the territories of Britain. A brief period of “Romanisation” now occurred as the lowland territories saw a series of construction projects, roads and infrastructure that would have been the foundations of a new Roman province.

It is likely that Rome had intended to continue campaigning and expand the borders of Britannia from coast to coast, but Rome recalled Agricola and necessitated a troop withdrawal.

Tacitus’ statement on his account of the Roman history between 68 AD and 98 AD: “Perdomita Britannia et statim missa” “Britain was completely conquered and immediately let go”, denotes his bitter disapproval at the failure to unify the whole island under Roman rule after Agricola’s successful campaigning in Caledonia.

In later years, the accepted frontier of the Roman territory and Caledonia was fixed south of the Cheviot Hills by the Emperor Hadrian with the construction of Hadrian’s Wall in 122AD. The frontier was moved further north around 142AD when the Antonine Wall was built between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde (west of Edinburgh along the central belt of Scotland).

The Romans retreated to Hadrian’s Wall a decade later but reoccupied the Antonine wall temporarily in 208AD under the orders of Emperor Septimius Severus (this has led to the wall being referred also as the Severan Wall).

Following the final retreat to Hadrian’s Wall, incursions by the Romans were generally limited to scouting expeditions in the buffer zone that developed between the walls, trading contacts, bribes to purchase truces from the natives, and eventually the spread of Christianity.

The archaeological legacy of Roman Caledonia demonstrates a failed attempt at creating a Roman state through military intervention.

The surviving archaeology (that includes the countless forts, marching camps and around 400 miles of roads across the Scottish landscape) has given archaeologists a valuable glimpse into a militaristic approach to subdue a native population, rather than the less forceful techniques of Romanisation applied in the rest of Britannia through bribery, building works and cultural assimilation.

Map of Roman forts & fortifications in Caledonia – To view the full map on mobile or desktop – Click Here