The modern human face is distinctively different to that of our near relatives and now researchers believe its evolution may have been partly driven by our need for good social skills.

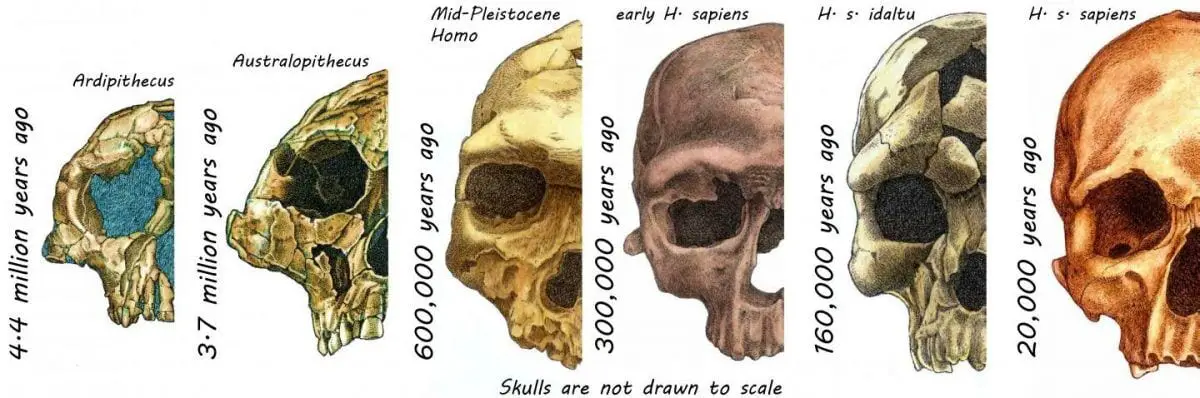

As large-brained, short-faced hominins, our faces are different from other, now extinct hominins (such as the Neanderthals) and our closest living relatives (bonobos and chimpanzees), but how and why did the modern human face evolve this way?

A new review published in Nature Ecology and Evolution and authored by a team of international experts, including researchers from the University of York, traces changes in the evolution of the face from the early African hominins to the appearance of modern human anatomy.

They conclude that social communication has been somewhat overlooked as a factor underlying the modern human facial form. Our faces should be seen as the result of a combination of biomechanical, physiological and social influences, the authors of the study say.

The researchers suggest that our faces evolved not only due to factors such as diet and climate, but possibly also to provide more opportunities for gesture and nonverbal communication – vital skills for establishing the large social networks which are believed to have helped Homo sapiens to survive.

“We can now use our faces to signal more than 20 different categories of emotion via the contraction or relaxation of muscles”, says Paul O’Higgins, Professor of Anatomy at the Hull York Medical School and the Department of Archaeology at the University of York. “It’s unlikely that our early human ancestors had the same facial dexterity as the overall shape of the face and the positions of the muscles were different.”

Instead of the pronounced brow ridge of other hominins, humans developed a smooth forehead with more visible, hairy eyebrows capable of a greater range of movement. This, alongside our faces becoming more slender, allows us to express a wide range of subtle emotions – including recognition and sympathy.

“We know that other factors such as diet, respiratory physiology and climate have contributed to the shape of the modern human face, but to interpret its evolution solely in terms of these factors would be an oversimplification,” Professor O’Higgins adds.

The human face has been partly shaped by the mechanical demands of feeding and over the past 100,000 years our faces have been getting smaller as our developing ability to cook and process food led to a reduced need for chewing.

This facial shrinking process has become particularly marked since the agricultural revolution, as we switched from being hunter gatherers to agriculturalists and then to living in cities – lifestyles that led to increasingly pre-processed foods and less physical effort.

“Softer modern diets and industrialised societies may mean that the human face continues to decrease in size”, says Professor O’Higgins. “There are limits on how much the human face can change however, for example breathing requires a sufficiently large nasal cavity.”

“However, within these limits, the evolution of the human face is likely to continue as long as our species survives, migrates and encounters new environmental, social and cultural conditions.”

Header Image – Australopithecus Africanus – Credit : José Braga;Didier Descouens