Using two partially fragmented fossil skulls, a student at the University of Bristol has digitally reconstructed, in three-dimensions, the skulls of two species of ancient reptile that lived in the Late Triassic, one of which had been previously known only from its jaws.

The research was completed by Sofia Chambi-Trowell, an undergraduate in Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences, as part of her final-year project for her degree in Palaeobiology.

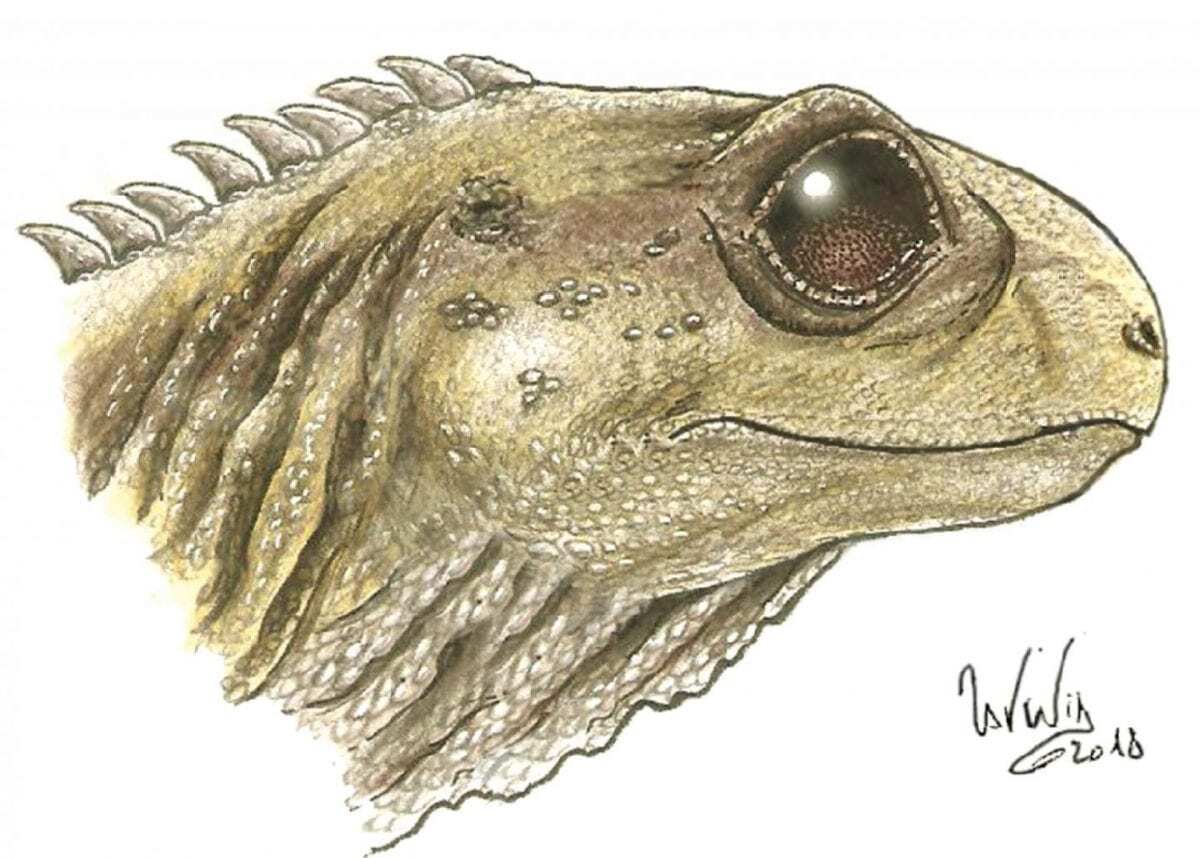

Clevosaurus was a lizard-like reptile that was first named back in 1939 from specimens found at Cromhall Quarry, near Bristol.

Since then, similar beasts have been found elsewhere around Bristol and in South Wales, as well as in China and North America. Clevosaurus was an early representative of an ancient group of reptiles called Rhynchocephalia, which today is represent only by the tuatara of New Zealand.

In her project, Sofia worked on new fossils of Clevosaurus hudsoni, the first species to be named, and Clevosaurus cambrica, which was named from a quarry site in South Wales in 2018.

She used CT scans of both skulls to reconstruct their original appearance, and she found evidence that the two species, which lived at the same time in the Late Triassic, some 205 million years ago, showed significant differences.

Sofia said: “I found that Clevosaurus cambrica was smaller overall and had a narrower snout than Clevosaurus hudsoni.

“Other differences include the number, shape and size of the teeth in the jaws, suggesting the two species fed on different food.”

Clevosaurus probably ate insects. Clevosaurus cambrica has corkscrew-shaped teeth which suggests it was able to shred the insect carcass by the natural twist as it drove its teeth through the hard carapace.

Clevosaurus hudsoni had teeth more adapted for simply slicing the prey. This might suggest that Clevosaurus cambrica ate larger or harder-shelled insects like beetles or cockroaches, while Clevosaurus hudsoni ate worms or millipedes which were less tough.

Professor Mike Benton, one of Sofia’s project supervisors, added: “Sofia’s work is a great example of how modern technology like CT scanning can open up information we would not know about.

“It took a lot of work, but Sofia has uncovered a good explanation of how many species of Clevosaurus could live side by side without competing over food.”

Her other supervisor, Dr David Whiteside, said: “Two hundred million years ago, Bristol lay much further south than it does today – about the same latitude as Morocco.

“Also, sea level was higher, so the peaks of limestone hills south of Bristol and in South Wales were islands, like Florida today.

“They were full of dinosaurs, early mammals, and rhynchocephalians feeding on the rich, tropical plants and insects. Sofia’s work helps us understand so much about this extraordinary time when dinosaurs were just taking over the world.”

Header Image – Life image of Clevosaurus. Image by Sophie Chambi-Trowell.