New research suggests that the last common ancestor of apes–including great apes and humans–was much smaller than previously thought, about the size of a gibbon. The findings, published today in the journal Nature Communications, are fundamental to understanding the evolution of the human family tree.

“Body size directly affects how an animal relates to its environment, and no trait has a wider range of biological implications,” said lead author Mark Grabowski, a visiting assistant professor at the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen in Germany who conducted the work while he was a postdoctoral fellow in the American Museum of Natural History’s Division of Anthropology. “However, little is known about the size of the last common ancestor of humans and all living apes. This omission is startling because numerous paleobiological hypotheses depend on body size estimates at and prior to the root of our lineage.”

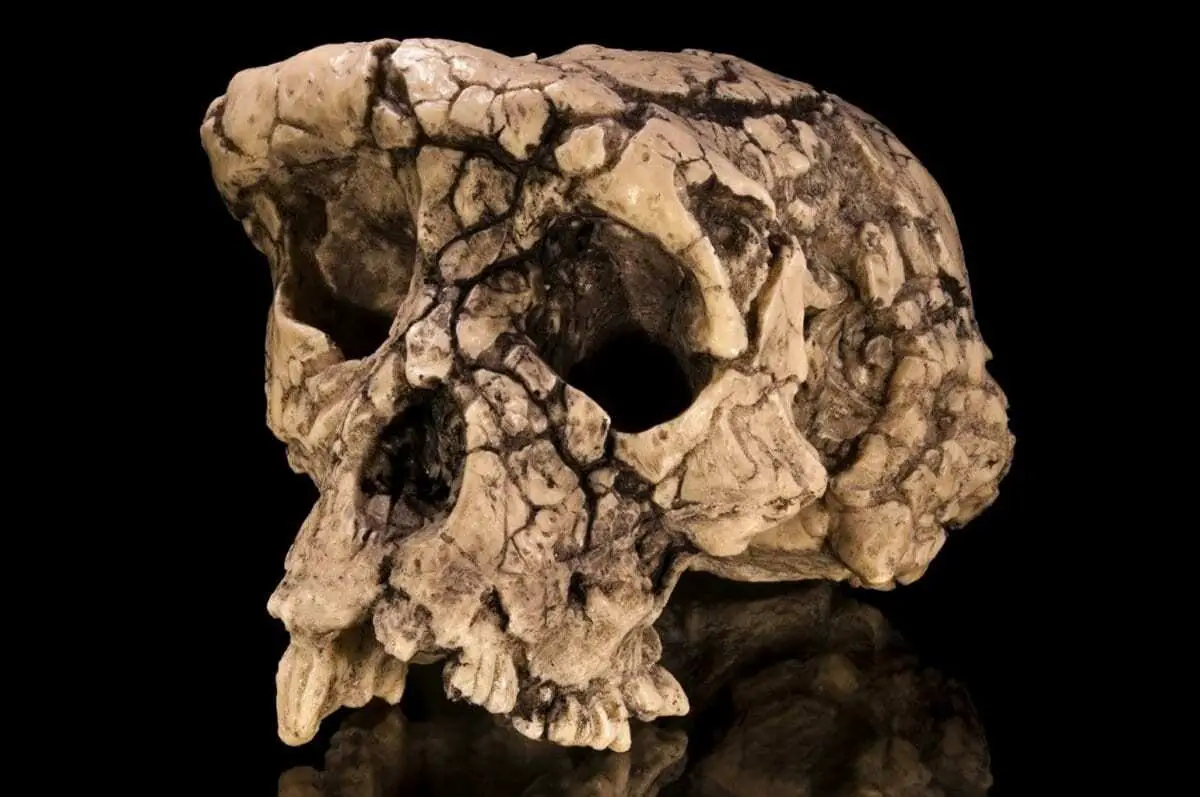

Among living primates, humans are most closely related to apes, which include the lesser apes (gibbons) and the great apes (chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans). These “hominoids” emerged and diversified during the Miocene, between about 23 million to 5 million years ago. Because fossils are so scarce, researchers do not know what the last common ancestors of living apes and humans looked like or where they originated.

To get a better idea of body mass evolution within this part of the primate family tree, Grabowski and coauthor William Jungers from Stony Brook University compared body size data from modern primates, including humans, to recently published estimates for fossil hominins and a wide sample of fossil primates including Miocene apes from Africa, Europe, and Asia. They found that the common ancestor of apes was likely small, probably weighing about 12 pounds, which goes against previous suggestions of a chimpanzee-sized, chimpanzee-like ancestor.

Among other things, the finding has implications for a behavior that’s essential for large, tree-dwelling primates: it implies that “suspensory locomotion,” overhand hanging and swinging, arose for other reasons than the animal simply getting too big to walk on top of branches. The researchers suggest that the ancestor was already somewhat suspensory, and larger body size evolved later, with both adaptations occurring at separate points. The development of suspensory locomotion could have been part of an “arms race” with a growing number of monkey species, the researchers said. Branch swinging allows an animal to get to a prized and otherwise inaccessible food–fruit on the edges of foliage–and larger body would let them engage in direct confrontation with monkeys when required.

The new research also reveals that australopiths, a group of early human relatives, were actually on average smaller than their ancestors, and that this smaller size continued until the arrival of Homo erectus.

“There appears to be a decrease in overall body size within our lineage, rather than size simply staying the same or getting bigger with time, which goes against how we generally think about evolution,” Grabowski said.

AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Header Image Credit – Didier Descouens