Recently published research reveals the discovery of a dun and the complex history of an archetypal Iron Age settlement in Scotland.

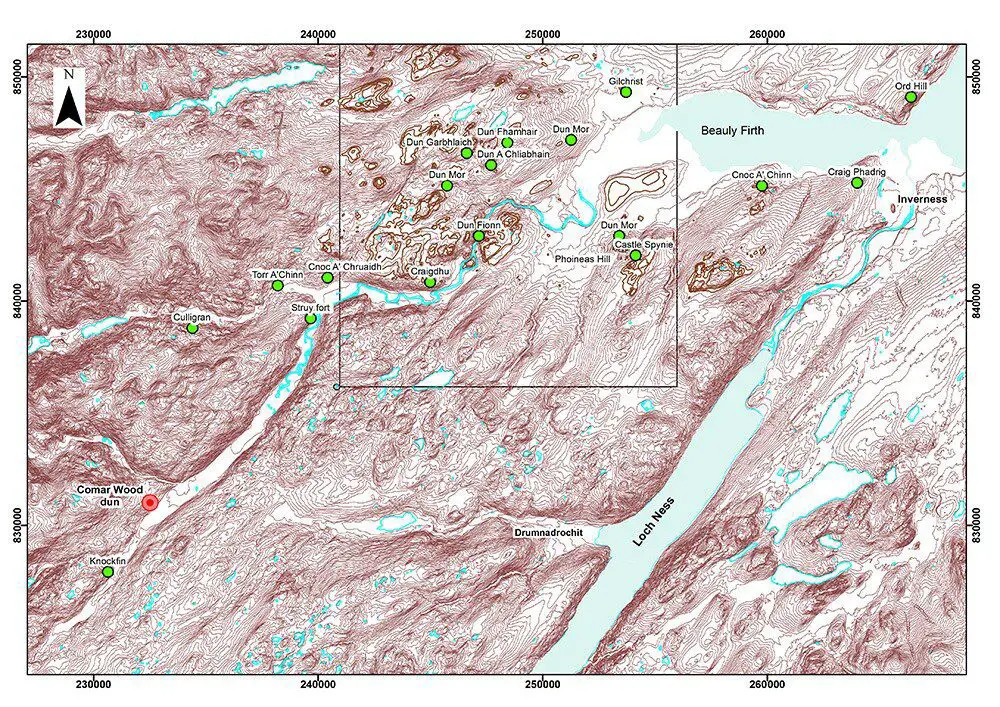

This archaeological ruin was discovered in 2010 by Forest District staff in Comar Wood in Strathglass near Inverness, and an archaeological survey and excavation were subsequently carried out on behalf of Forestry Commission Scotland. The appearance of the monument before excavations commenced in 2013 suggested that the site was possibly a broch or a dun. These stone-built structures have long been a dominant feature in the study of the Scottish Iron Age, and their classification and development has provided much debate. It is difficult to accurately interpret the features of such sites from survey alone and within the surrounding landscape of Strathglass, a wide range of potentially contemporary sites were known, including forts, duns and brochs. Few of these sites have been excavated or investigated in any detail. Only excavation could provide evidence that might help to address the recent identification of the central Highlands as a ‘black hole’ in terms of understanding the context of enclosed places by the Scottish Archaeological Research Framework panel.

Comar Wood Dun occupies a prominent site overlooking Strathglass. The central dun structure comprised a circular drystone wall with inner and outer facing stones, appearing as a large roundhouse with an internal diameter of about 13 m. Although portrayed as simple in form, duns are a very diverse class of monument, possessing a variety of ground plans, which include the possible roofed ‘dun-houses’ as well as the much larger ‘dun enclosures’ that were almost certainly unroofed and were more like the much later Irish ring forts. A good interpretation for this site would be that it was a dun-house – a substantial monument that is too small to be a fort and could have been roofed – within a defensive enclosure.

The excavation revealed that Comar Wood Dun had been constructed during the second half of the first millennium BC. Evidence for two burning events was uncovered, after both of which events the site was rebuilt and reused for several centuries before final abandonment. The rebuilding of Comar Wood Dun is consistent with other Iron Age Atlantic roundhouse sites. However, in stark contrast to many brochs, the excavations at Comar Wood failed to produce any dateable small finds, which has also been the case for other duns. The lack of material culture suggests either that the occupants thoroughly cleaned out debris in a methodical manner, before or after abandoning such sites, or that they were only used temporarily, possibly as places to retire to in times of strife. The reuse of these sites and lack of artefactual material suggest that they were not elite settlements, but probably related to more autonomous farming communities establishing a presence and control over territory.

That so few artefacts were recovered, and such little domestic debris encountered, may suggest that the Comar Wood Dun evolved from a local defended roundhouse into a meeting place, a monument located centrally that could have been visited occasionally. Such an interpretation might also offer an explanation as to why so much secondary destruction debris was banked up against the inside of the structure rather than being cleared out completely as would be expected in a permanent settlement structure.

Like most of the forts, duns and brochs distributed along Strathglass, the Comar Wood Dun’s location took full advantage of extensive views; whether to work on established lines of sight between contemporary structures, to provide a defensive location, or to represent a symbol of status within the wider landscape. With its impressive dimensions, including a possible towering conical roof, outworks and its location set on the edge of rocky knoll whose slopes fall quickly towards the valley floor, the monument would certainly have displayed an element of identity and prestige.

While further excavation of this site and other similar sites would reveal much more information, the excavation Comar Wood has shown that ‘keyhole’ investigations, designed to assess archaeological potential and recover information to a pre-determined plan, can provide valuable information and usefully increase the current corpus of knowledge. A carefully constructed research design and effective trench placement gained the optimum amount of information from a small area. The excavation also proved that it is difficult to assign a monument-type based on field survey alone; such monuments should be approached with an open-mind and can only be truly categorised through excavation. It was shown that what was thought from the surface to be a well-preserved galleried dun was, in fact, a poorly preserved monumental roundhouse with a timber structure in the entrance.

The full results of this research, which was funded by Forestry Commission Scotland, ARO23: Excavation and Survey at Comar Wood Dun, Cannich, Strathglass, Inverness-shire by Mary Peteranna and Steven Birch is freely available to download from the ARO website – Archaeology Reports Online.

Header Image – Comar Wood dun at the time of its original discovery in 2010 © ARO.