The Upper Palaeolithic is best understood period of the Old Stone Age, beginning shortly after the extinction of Homo neanderthalensis and the encroachment of the new hominin Homo sapiens from Africa into Europe.

The Upper Palaeolithic is marked by the dominance of artefacts, left behind by our ancestors. When compared to more recent times particularly to the advent of farming 10,000 years ago, evidence for how our Upper Palaeolithic ancestors lived and ordered their societies is very much lacking. Recently, questions are beginning to be raised about how we prejudge Upper Palaeolithic hominins.

Claire Heckel of the American Museum of Natural History, in association with the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) wants to harness the power of statistics and the archaeological record to understand the level societal complexity. Many decades ago, archaeologists assumed that early hunter-gatherers were simple people with simple societal structure. The rise of farming in the fertile crescent was argued to be a sharp contrast to what came before, with the sudden need to settle, develop states and thereafter kingdoms. Archaeologist today can’t entirely shed their idea of the contrast between the two moments in time. The question here is: Have we exaggerated the simplicity of Upper Palaeolithic hominins?

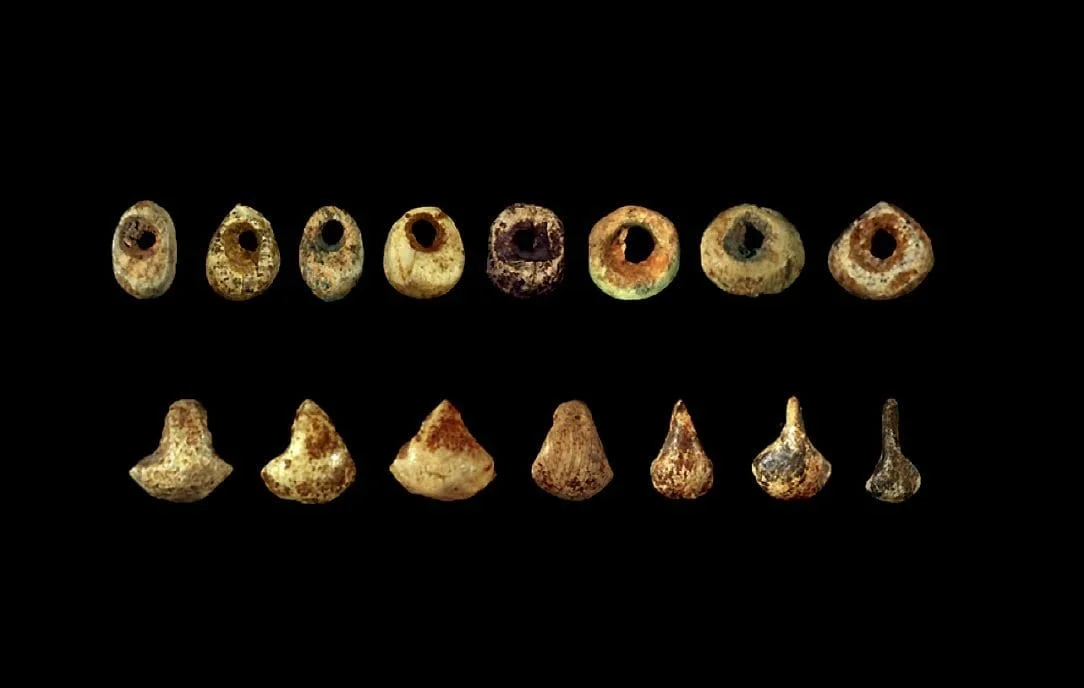

In order to begin to answer this question, we first need to find evidence of how Upper Palaeolithic society was structured. Heckel was very interested in what a tiny insignificant object like a bead could tell us about Upper Palaeolithic society. These Basket-shaped beads were found at four archaeological caves and rock shelters in Aquitaine, southern France. The beads are extremely interesting due to the projected time and effort needed to craft them. Some of the beads were made from steatite (soapstone), which is a talc-schist metamorphic rock, which got its name from the soapy feel of the talc in the rock. While others were crafted from mammoth ivory, broken into segments in a five-stage process.

The archaeological record has not always been very clear in shedding light on the past and so many anthropologists have appealed to ethnography to help explain what we see in the archaeological record. Many forget that what happens to the Kalahari Bushmen cannot count as a way of explaining the Upper Palaeolithic hominins of frozen Europe. The first archaeologists to try to use ethnography, was Dr. Lewis Binford who lived with the Nunamuit of Alaska as a way of peeking into life in Late Glacial Europe. This was flawed logic because it does not count as evidence and we need to return to the archaeological record to the direct clues. That is what Claire Heckel is doing here, by using morphometric analysis of 402 basket-shaped beads, the level of standardisation can be quantified.

Taking 6,432 data points on the 402 basket-shaped beads, Heckel used Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to compare and contrast the shape and form of the beads from 4 cave and rock shelter sites. The results suggested that bead production was a highly standardised process and the statistical analyses were compared to those of Neolithic and Bronze age archaeological sites throughout the world, the level of mastery was comparable to the bead production specialisation during the advent of farming. There has been some debate as to how we should describe craft work in the Upper Palaeolithic.

For example, Jacques Pelegrin argued in 2007, that the word Mastery should be used to describe intensive craft work in the Upper Palaeolithic, while the word specialisation should be used to describe intensive craft work in the Neolithic. This debate continues today but however you phrase it, there is exchange taking place in the region of Aquitaine, southern France. Exposures of Steatite are easily identifiable compared to mammoth ivory, part of a biological organism that roamed the landscape. We can gauge the distance the steatite travelled from the source to the cave or rock shelter sites, an impossible task to overcome when it comes to ivory.

Heckel proposed three different models to explain the archaeological record in Aquitaine. Model 1 suggested that there was a single point in the region, where these beads were produced and distributed from there. Model 3 suggested that the Upper Palaeolithic nomadic groups crafted the beads at the four caves sites. But it was Model 2 that best fitted the above statistical analyses, suggesting that there were multiple territories with their own individual centre of production, while exchange and distribution resulted in the deposition at the cave and rock shelter sites. Heckel’s work is only the beginning of a long research process to see if we have exaggerated the simplicity of Upper Palaeolithic societal structure. Based on the basket-shaped beads found at the early Aurignacian archaeological sites, a small group of people appear to be spending a great deal of time crafting these beautiful objects.

Written by Charles T. G. Clarke