Paleontologists at the University of Alberta have developed a new theory to explain why the ancient ancestors of dinosaurs stopped moving about on all fours and rose up on just their two hind legs.

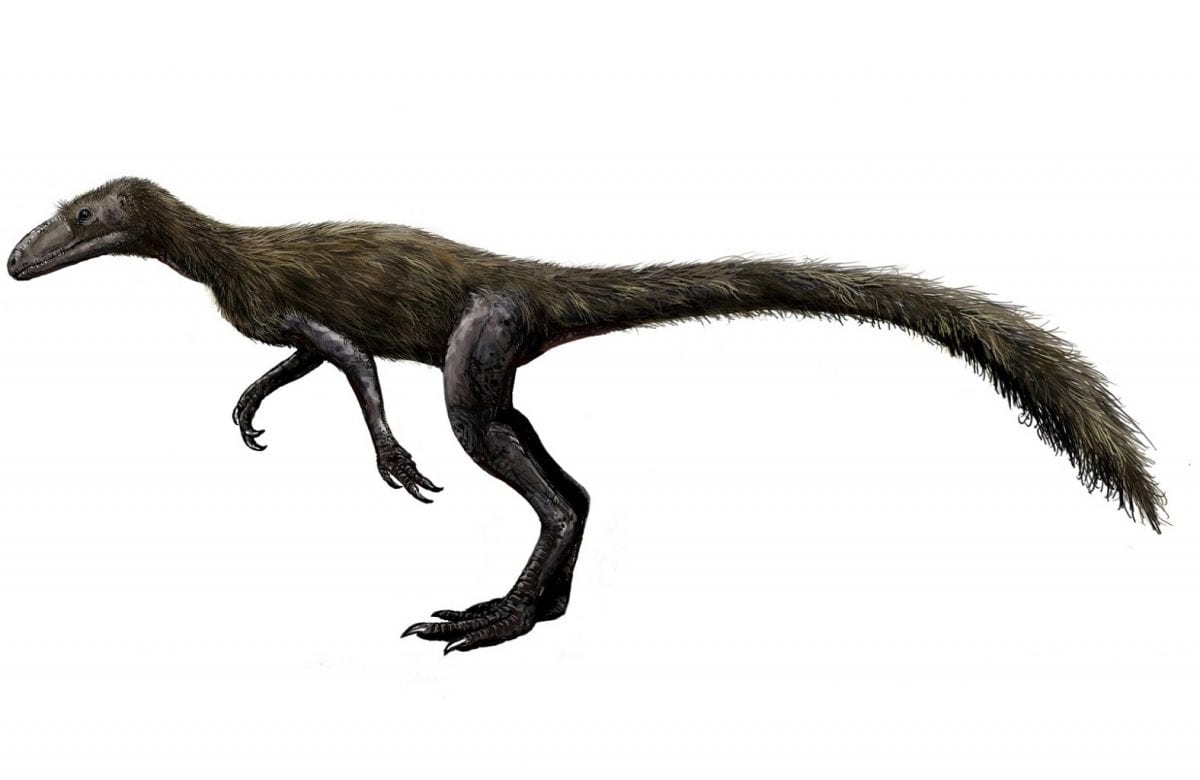

Bipedalism in dinosaurs was inherited from ancient and much smaller proto-dinosaurs. The trick to this evolution is in their tails explains Scott Persons, postdoctoral fellow and lead author on the paper.

“The tails of proto-dinosaurs had big, leg-powering muscles,” says Persons. “Having this muscle mass provided the strength and power required for early dinosaurs to stand on and move with their two back feet. We see a similar effect in many modern lizards that rise up and run bipedally.”

Over time, proto-dinosaurs evolved to run faster and for longer distances. Adaptations like hind limb elongation allowed ancient dinosaurs to run faster, while smaller forelimbs helped to reduce body weight and improve balance. Eventually, some proto-dinosaurs gave up quadrupedal walking altogether.

The research, conducted by Persons and Phil Currie, renowned paleontologist and Canada Research Chair, also debunks theories that early proto-dinosaurs stood on two legs for the sole purpose of free their hands for use in catching prey.

“Those explanations don’t stand up,” says Persons. “Many ancient bipedal dinosaurs were herbivores, and even early carnivorous dinosaurs evolved small forearms. Rather than using their hands to grapple with prey, it is more likely they seized their meals with their powerful jaws.”

But, if it is true that bipedalism can evolve to help animals run fast, why aren’t mammals like horses and cheetahs bipedal?

“Largely because mammals don’t have those big tail-based leg muscles,” Persons explains. “Looking across the fossil record, we can trace when our proto-mammal ancestors actually lost those muscles. It seems to have happened back in the Permian period, over 252 million years ago.”

At that time the mammalian lineage was adapting to dig and to live in burrows. In order to dig, mammals had strong front limbs. Muscular back legs and tails likely made it more difficult to maneuver in the narrow confines of a burrow.

“It also makes the distance a predator has to reach in to grab you that much shorter,” says persons. “That’s why modern burrowers tend to have particularly short tails. Think rabbits, badgers, and moles.”

The researchers also theorize that living in burrows may have helped our ancestors to survive a mass extinction that occurred at the end of the Permian. But when proto-mammals emerged from their burrows, and some eventually evolved to be fast runners, they lacked the tail muscles that would have inclined them towards bipedalism.