In the paleontology popularity contest, studying the social life of dinosaurs is on the rise.

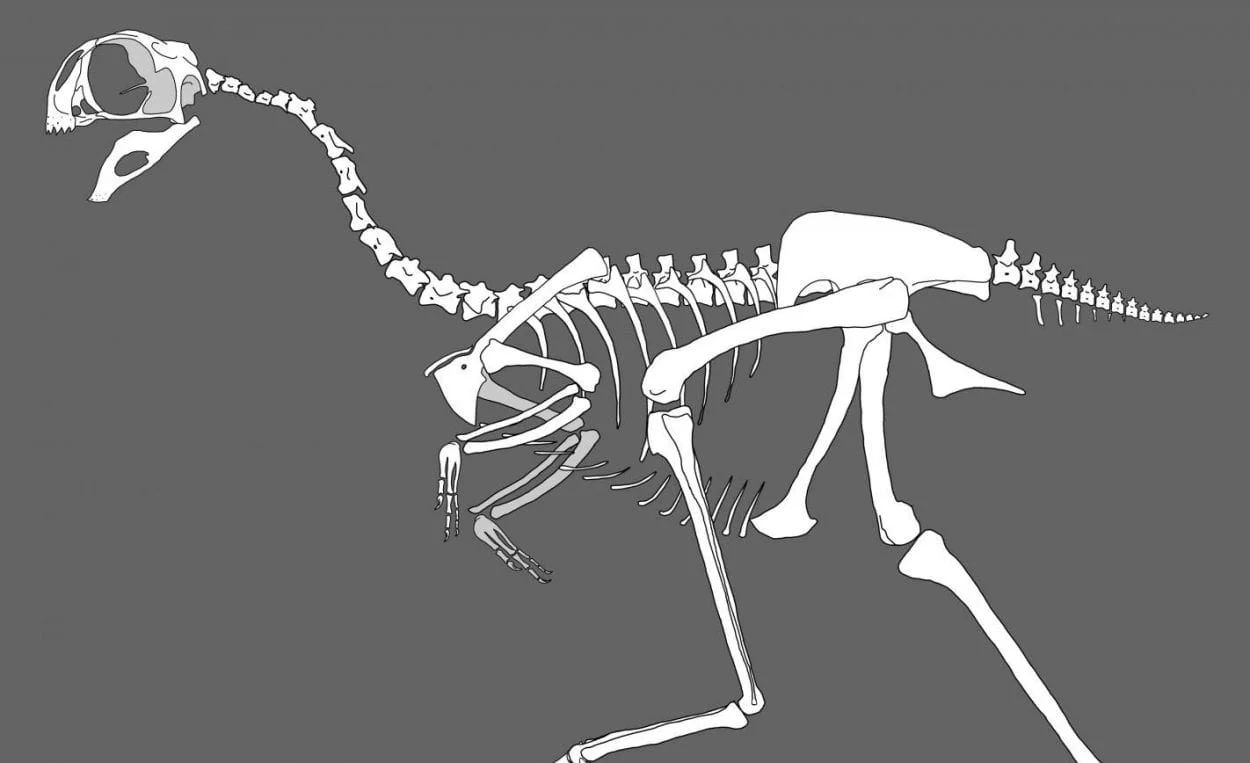

A new publication on the bird-like dinosaurAvimimus, from the late-Cretaceous suggests they were gregarious, social animals–evidence that flies in the face of the long-held mysticism surrounding dinosaurs as solo creatures.

“The common mythology of dinosaurs depicts solitary, vicious monsters running around eating everything,” explains Gregory Funston, PhD student and Vanier scholar at the University of Alberta. “Our discovery demonstrates that dinosaurs are more similar to modern animals than people appreciate. Although the players are different, this evidence shows that dinosaurs were social beings with gregarious behaviour who lived and died together in groups.”

The discovery comes from a site in Mongolia, first encountered by paleontologists a decade ago. The site contained thousands of shards of destroyed bone, belying the telltale evidence of a previous discovery by fossil poachers. After conducting additional field work, scientists discovered a bonebed with an assemblage of Avimimus dinosaurs, who were extremely rare prior to this discovery.

Funston, who has traveled to Mongolia several times to work on the material, explains that though it is common knowledge that modern birds form flocks, this is the first evidence of flocking behavior in bird-like dinosaurs.

“With an assemblage like this, you can’t really understand why the dinosaurs died together unless you see the field site,” says Funston. “We can tell that they were living together around the time of death, but the mystery still remains as to why.”

What the paleontologists do know is that the discovery highlights the potential trend of increasing gregariousness and social behaviour in dinosaurs.

“There are groups of dinosaurs that become social towards the end of the Cretaceous. What still remains to be solved is whether this increasing trend is based on dinosaur behavior or it if it’s because of how the fossils were preserved.”

Bonebeds provide good evidence that the animals were living together in herds or groups. Though rare in the Jurassic and Triassic, they dominate the Cretaceous period. However, this is the first discovery of a bonebed of bird-like dinosaurs.

Funston says that perhaps more important than the scientific findings is shedding light on the increasing incidence of fossil poaching and how this affects scientific understanding. For this reason, he and his co-authors have published their findings in the open-access Scientific Reports, part of the Nature group of scientific journals. Inspired by their mentor who has been working in Mongolia since the 1980s, Currie’s students have taken up not only the scientific cause but also the higher social justice to protect our shared heritage.

The actor Nicholas Cage made headlines in late-2015 when he returned a Tarbosaurus skull to Mongolia–purchased in an auction where he beat out another fossil-loving film star Leonardo DiCaprio–after learning the fossil was poached. Funston says without buyers, the fossil poaching market will dry up, so it is critical to raise awareness of the crime.

“Exposing poaching is almost more important than the science, because cutting off this crime will let the science continue. It changes our attitude about fossils,” says Funston. “They shouldn’t be seen as collectors’ objects but rather as evidence of our shared heritage that helps us understand where we came from and where we are going. To work as part of a team that is helping to ameliorate the situation is a great honour.”