An international team of scientists announced the discovery Thursday of a new species of hominin, a small creature with a tiny brain that opens the door to a new way of thinking about our ancient ancestors.

The discovery of 15 individuals, consisting of 1,550 bones, represents the largest fossil hominin find on the African continent.

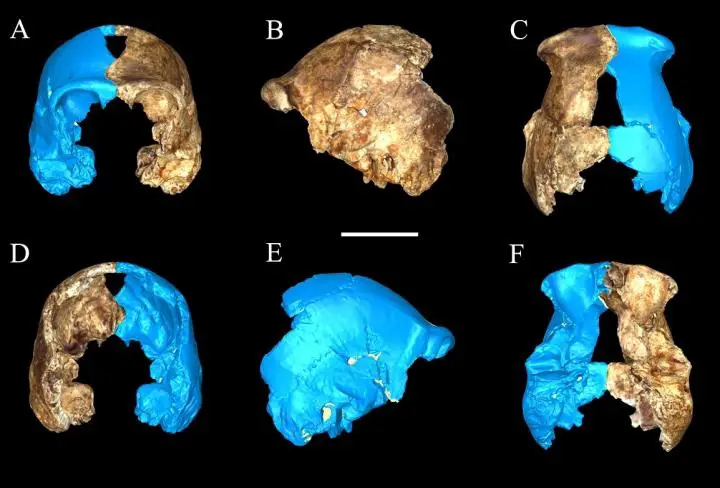

“We found adults and children in the cave who are members of genus Homo but very different from modern humans,” said CU Denver Associate Professor of Anthropology Charles Musiba, PhD, who took part in a press conference Thursday near the discovery inside the Rising Star Cave in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site outside Johannesburg, South Africa. “They are very petite and have the brain size of chimpanzees. The only thing similar we know of are the so-called `hobbits’ of Flores Island in Indonesia.”

Homofloresiensis or Flores Man was discovered in 2003. Like this latest finding, it stood 3.5 five feet high and seems to have existed relatively recently though the exact age is unknown.

Caley Orr, PhD, an assistant professor of cell and developmental biology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, analyzed the fossil hands.

“The hand has human-like features for manipulation of objects and curved fingers that are well adapted for climbing,” Orr said. “But its exact position on our family tree is still unknown.”

The new species has been dubbed Homonaledi after the cave where it was found – naledi means `star’ in the local South African language Sesotho.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the discovery is that the bodies appear to have been deposited in the cave intentionally. Scientists have long believed this sort of ritualized or repeated behavior was limited to humans.

The team of 35 to 40 scientists was led by Lee Berger, research professor in the Evolutionary Studies Institute at the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa. It was supported by the National Geographic Society and the National Research Foundation. The October issue of National Geographic magazine will feature the discovery as its cover story. It will also be the subject of a NOVA/National Geographic Special airing Sept. 16.

Getting inside the Dinaledi chamber of the remote cave system was difficult, requiring the help of six `underground astronauts,’ who squeezed through a 7-inch wide gap to reach the remains.

“The chamber has not given up all of its secrets,” said Berger, a National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence. “There are potentially hundreds if not thousands of remains of H. naledi still down there.”

The announcement coincides with the publication of two studies about the new species in the journal eLife, co-authored by Musiba and Orr.

In it, the researchers try to place Homonaledi in context with other species. Generally speaking, they say, there is an assumption that any new group of fossils must belong to an existing species.

But it’s not that simple here.

“Assigning these remains to any known species of Homo is problematic,” the study said. “While Homo(naledi) shares aspects of cranial and mandibular morphology with Homohabilis,Homorudolfensis, Homoerectus, MP Homo and Homosapiens, it differs from all of these taxa in its unique combination of derived cranial vault, maxillary, and mandibular morphology.”

The study suggests that Homonaledi most closely resembles Homoerectus with its small brain and body size. Yet it also resembles Australopithecus which highlights its own uniqueness.

Complicating matters is the fact that researchers still don’t know the exact age of the fossil site.

“If these fossils are late Pliocene or early Pleistocene, it is possible that this new species of small-brained, early Homorepresents an intermediate between Australopithecus andHomoerectus,” the study said.

That would also make the new species very old.

But if the fossils are more recent, they theorize, it raises the possibility that a small-brainedHomolived in southern Africa at the same time as larger brained Homospecies were evolving.

“This raises many questions,” Musiba said. “How many species of human were there? Were their lines that simply extended outward and then disappeared? Did they co-exist with modern humans? Did they interbreed?”

Homonaledi has a chest similar to a chimpanzee and hands and feet proportionate with modern humans, though with curved fingers.

“They would have had great climbing ability,” said Musiba. “The oldest adults were about 45 and the youngest were infants.”

He described poring over the bones late at night as akin to `hitting the jackpot.’

“You just didn’t want to go home because it was so exciting,” he said. “I felt like a kid in a candy store.” The find represents another milestone in Musiba’s efforts to advance the understanding of our earliest human relatives.

As director of CU Denver’s Tanzania Field School, he takes groups of students each year to gain hands-on experience working in and around the famed Laetoli hominin footprints site and Olduvai Gorge where some of the oldest hominin remains have been found.

Not long ago, they discovered ancient footprints of lions, rhinos and antelopes near those of the early hominins.

And last year, Musiba was appointed to an international team of advisors dedicated to building a museum complex in Tanzania to showcase a collection of 70 hominin footprints, estimated at 3.6 million years old. They are considered the earliest example of bipedalism among hominins.

Musiba said the Rising Star expedition was notable for getting so many anthropologists to work together.

“Anthropology can be a cut-throat profession with all these scientists scrambling for limited resources,” he said. “To me one of the most exciting aspects of this research was the collaborative nature of it.”

UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO ANSCHUTZ MEDICAL CAMPUS